The white 5-gallon bucket in the corner of David Presti’s office contains a human brain, about three pounds of coiled brownish fat and tissue. With its weight in my cupped hands, I marvel that it had once thought, that it had marveled. How is the varied spectrum of human thought and feeling related to this bland mass?

"How the mind is connected to the brain is arguably the greatest unsolved problem in science," Presti says, interrupting my thoughts. He peers through his half-moon shaped glasses. "We haven’t got a clue, yet, how physical processes in the brain give rise to our experiencing a thought."

Although complete understanding of the brain is still a speck on the horizon, the past decade saw a remarkable twist in how we view the relationship between the physical brain of nerve cells and connective tissue and the intangible mind of thought and feeling. Scientists once believed that the adult brain could not grow or change. Now we know that adults do grow new brain cells and that behavior can affect brain development. Evidence is mounting that, like using particular physical exercises to develop certain muscle tissues, people may be able to perform specialized mental exercises to target specific areas of the brain. At least one of these brain-building activities requires no physical motions whatsoever: meditation.

For centuries, Buddhists practiced meditation to consciously improve their mental control over focus and emotion. Scientists now are comparing the brains of meditators and non-meditators to learn whether meditation does affect the brain, as the Buddhists claim. It seems that it does.

Scientists are documenting the claims of meditators and translating the perceived changes into scientific lingo. Where the Buddhist says, "Meditation brings more focus and brain power," the scientist says, "Meditators have increased gamma brain wave activity." Where the Buddhist says, "Meditation provides resistance to stress," the scientist says, "Meditators have increased serotonin levels and decreased cortisol and adrenaline." Where the Buddhist says, "Meditation increases happiness," the scientist says, "Meditators have increased the left to right prefrontal cortex activity ratio." Through using the most modern

Western scientific techniques, scientists are now discovering what ancient Eastern philosophy has maintained for centuries. The mind can control and alter the brain.

Scientist Meets Monk

Presti traveled to India to assist John Pettigrew, a neuroscientist at the University of Queensland, in testing the perceptions of monks. Pettigrew studies how the brain processes visual signals. He outfits his volunteers with special goggles that show vertical stripes to one eye and horizontal stripes to the other. The brain doesn’t fuse the images into a grid, as might be expected. Instead, the volunteer sees one image, then the other, then the first again — a process called "binocular rivalry." People can’t consciously control this switching rate, which is considered an innate brain property.

Given an opportunity during the summer of 2003, Pettigrew grabbed his graduate student and Presti, his Californian friend with the brain bucket, and flew to India. There they put goggles on meditating monks, who reported a slower rate of switching in the binocular rivalry experiments than did non-meditating subjects. This is tantalizing evidence that the monks’ meditation exercises affect the wiring of their brains on a deep level.

Pettigrew and Presti represent the current trend of neuroscientists testing their favorite experiments on the trained minds of meditators. While meditation research is still in its infancy, the unfolding story of meditation’s physiological effects is remarkably consistent, both with our knowledge of neuroscience and with anecdotal reports of those who practice meditation.

Tibetan Buddhist tradition teaches meditation as a way to understand the mind and train the brain. Through repeated practice, meditators strive to control negative emotion and increase happiness. Multitasking Westerners have long admired the traits seen in meditation masters: strong focusing and attention skills, adept control of emotion, conscious control of basic body rhythms like heart rate and temperature, and resistance to illness. The Buddhists believe these manipulations are the intentional outcome of focused attention.

Tibetan Buddhist philosophy describes four mental states explored through meditation. Intense concentration on an object is called "focused attention." "Open attention" lets the mind wander without perception or judgment. "Visualization" entails reconstructing an object in the mind’s eye. Abandoning the mind to feelings of pure love and compassion to discourage self-centered thoughts is called "compassion." Similar to how using weight machines at the gym targets different muscle groups, these different meditation exercises affect the mind and the brain differently.

Researchers usually study the compassion style of meditation. Because it focuses on an abstract idea, not an object, scientists believe it may show the effects of meditation in their purest form, without interference of the visual or other sensory areas of the brain. Current research investigates some of the major claims of this ancient practice.

Claim 1: Meditation increases brain power

During meditation, heartbeat and breathing rates slow down, giving the meditator a sense of relaxation. This is different than sleeping, though, since the mind retains its waking awareness. This state is partially achieved by the release of a chemical that constricts the blood vessels, allowing blood pressure to remain constant even when the heart rate has decreased. This chemical, called arginine vasopressin, also helps new memories form, which may account for meditators’ vivid recall of their experiences.

Scientists measure the brain’s electrical activity to classify which type of consciousness a person is experiencing. The technology they use to do this is called EEG, short for electroencephalogram. Electrodes placed on the subject’s scalp record the brain’s electrical impulses. Wires attach the electrodes to a machine, which displays the impulses as waves. There are characteristic wave shapes for sleeping, relaxing, and thinking.

The relaxed brain creates a rounded, even wave shape called alpha waves. Scientists have known for decades that a meditating brain does produce alpha waves, no great surprise since meditation subjects report feelings of relaxation. But meditation is more than just relaxation.

Antoine Lutz, a neurobiologist in Robert Davidson’s laboratory at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, found a strong signature of something else entirely: a spiky, irregular wave form. As they described in a recent article in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Lutz, Davidson and their collaborators put electrodes on five people with significant meditation experience and measured their brain waves before, during, and after meditation.

They found a pronounced difference in the subject’s brains, during meditation and while not meditating. "There was a new signature that involved a very fast rhythm called a gamma rhythm, which is known to be involved in attention or sensory awareness or even in consciousness," Lutz says. Gamma waves indicate neural synchronicity, the coordination of different areas of the brain in highly ordered thought.

How can the meditating brain both have stimulating gamma waves and relaxing alpha waves? The trick is selectivity. The regions involved in focus and thought are active, while other regions not involved in the focus are inactive, Lutz says.

The involvement of gamma waves wasn’t surprising to Lutz. What astounded him was their intensity. "We were expecting an important role of this rhythm during meditation, but it’s extremely interesting that it’s so massive," Lutz says. "We are still trying to understand what it means in terms of the functions, but it’s quite spectacular."

The super-sized gamma activity may mean more brainpower, suggests Lutz. Meditation strengthens gamma activity in general, not just during practice. This may explain the higher attention and focusing skills long noted by Westerners, with a tinge of envy. Lutz found that people with more meditation experience had stronger brain activity. "And that’s interesting because meditation is supposed to induce some temporary and long-term change in experience," says Lutz. "It shows that meditation has the possibility to change the brain."

Claim 2: Meditation increases health

Meditation’s changes to the brain also affect the body. Numerous studies have found that people who meditate are physically healthier. They have stronger immune systems and don’t get cancer as often. Researchers don’t know if meditation causes these effects, but find the connection tantalizing enough to study.

A striking experiment led by neuroscientist Richard Davidson of the University of Wisconsin at Madison found that meditation training boosts immune response, even after just eight weeks. In the study, published in Psychosomatic Medicine in 2003, Davidson assigned 25 employees of a biotech company to a meditation course, while 16 of their co-workers did not receive training. After eight weeks, all volunteers were injected with a flu vaccine. Davidson found the natural immune response to the vaccine was much stronger in the group that was trained in meditation.

How could meditation boost health? It might have something to do with meditation lowering stress.

When a person faces a stressful situation, like an impending project deadline, an argument, or a bad driver in the next lane, stress chemicals are released into the brain. These neurotransmitters, including cortisol and adrenaline, cause physical changes. They speed heart rate, tense the muscles, and focus attention. This is a good response — it gets a person through a tough time. After the stressful situation is gone, the stress chemicals disappear and the body goes back to normal.

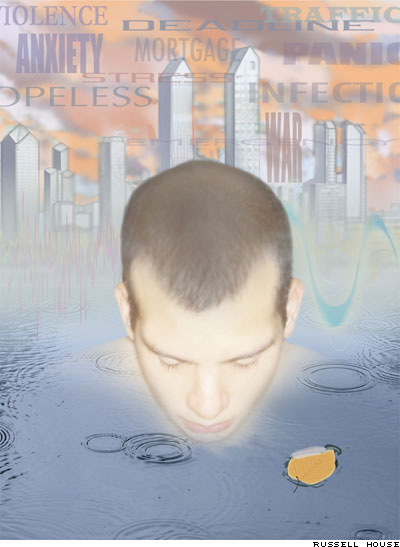

But in our modern world, stress is ever-present. A project is always due; someone is always stepping on your toes; and traffic is always frustrating. Living this way perpetually floods our brains with stress chemicals, which have devastating long-term effects. Physically, prolonged exposure to stress chemicals can lead to hypertension, diabetes, and cancer. Mentally, it can cause memory problems, post-traumatic stress syndrome, and depression.

Many studies show that meditation lowers all of these stress-induced problems. Additionally, scientists measured lower amounts of the stress chemicals themselves in meditators. "In general, people have found decreases in some of the stress hormone neurochemicals, like adrenaline and cortisol," says radiologist Andrew Newberg from the University of Pennsylvania Medical School.

When meditators are in a stressful situation, they have the same stress response as non-meditators, but they return to a normal state much faster than people who don’t. Doctors are already recommending meditation as a self-treatment for many diseases, although more research is needed to see if this is effective. "The challenge of science is to not just determine if there are physiological changes, but if these changes really affect health," says Newberg.

Claim 3: Meditation makes you happier

Brain functions map to specific areas. The human brain has three layers, rather like a Hostess Sno Ball (tm), the 3-inch chocolate cake, dome-like with a marshmallow coating and a white cream filling. The cream center of the brain is a primitive core that scientists call the "lizard brain." This area takes care of the basic life functions, like heartbeat, temperature regulation, and breathing. The chocolate cake layer surrounding the lizard brain is the "old mammalian brain," which allows fundamental emotions and social behaviors. The marshmallow shell of our brains is the specialized "new mammal brain," the cortex: the familiar labyrinth of grey matter where thinking and reasoning arise. Emotions may come from the cake and creamy filling, but scientists have found that the key to maintaining happiness lies in the outer marshmallow shell.

Until recently, scientists believed that each person had a natural set-point for happiness. No matter what good or bad serendipity might befall a person — winning the lottery or being diagnosed with a terminal illness — one’s state of happiness would sooner or later revert to the level before the event. This belief gained support from the finding that the ratio of activity in the portion of the brain behind the left vs. the right side of the forehead — the prefrontal cortex — reflects a person’s general mood. People who are usually more positive and happy have higher activity in the left side. People who are often more negative and depressed have higher activity in the right side.

However, studying the meditators’ brains has changed this view. Scientists are entertaining the possibility that meditation skews the prefrontal cortex ratio to the left, that meditation trains brains to be happy.

To measure the effects of meditation on brain activity, several labs have subjected Buddhists to an awkward and noisy horizontal meditation, including Davidson’s group and Sara Lazar’s group at Massachusetts General Hospital.

They used a brain mapping technique called fMRI, or functional magnetic resonance imaging, to pinpoint the active parts of the brain during meditation. The fMRI measures blood flow to chart the active parts of the brain, since active tissue requires more blood. During fMRI, a person lies inside a tube cut into a large scanning machine, which make rhythmic rumbling sounds like a clothes dryer. The resulting data is read on brain images, false-colored to highlight the active areas. They compare scans of meditating brains to scans of non-meditating brains to find the effects specific to meditation.

Both Davidson and Lazar found that meditation increases activity in some areas and decreases activity in others. The parts of the brain that control emotion are more active, while the parts that process sensory input are less active.

The fMRI studies found that the deeply concentrating meditators use the "thinking" part of the outer brain heavily. As one would expect from the Buddha’s blissful smile, meditating brains are especially active in the left prefrontal cortex, suggesting a propensity toward a good mood. Since thought pathways in the brain are reinforced with use, happy people tend to remain happy and depressed people tend to stay depressed. Regular meditation practice may strengthen the pathways that tip this cycle toward the sunny side. It may indeed be possible to become happier by practicing intentional brain training.

"Some claim that if people just sit for 20 or 30 minutes a day and just relax, they will get the same benefits as in meditation," says neurobiologist Lazar. "Our results suggest that there really is something going on in the brain, that they are not just sitting there."

MRI results may also explain why meditators often say they experience a feeling of "loss of their sense of self and a feeling of absorption," says Newberg. "They lose their typical boundary between the self and other and start to feel that they become connected with — or at one with — the object of their meditation." Researchers see a decrease of activity in the sides of the brain, called the parietal lobes, which provide a sense of what is self and what is not. Shutting down these regions could cause a lack of self-perception. This may be common to a variety of religious experiences. Newberg has detected the same deactivation of the parietal lobes in praying Franciscan nuns.

The ever-changing brain

The nuns and the Buddhists show that changes in the brain increase with the number of years they have meditated. Researchers saw an analogous phenomenon in the mid 1990s while studying people who play stringed instruments. Those who had played longest and practiced most had more development in the responsible brain regions. Neurobiologists coined the term "neuroplasticity" for the molding of the brain by experiences, through new nerve cells or new connections between nerve cells. Researchers now are invoking the same term for the brain changes that occur through meditation. Physical practices and mental practices have similar potential to develop and change the brain.

Rigorous scientific exploration into meditation is still new. But so far the results quantitatively show what people have said qualitatively for centuries. Meditation makes you happier, healthier, and less stressed. More strikingly, it also shows that people can train their brains like they train their bodies. Practicing focus brings focus. Practicing positive thought brings positive thought. Scientists are answering the "what" questions. The next questions are "how." So far, there isn’t even a working model for how the mind alters the brain. When asked, researchers shrug and mumble that they need to do more experiments.

"The connection between mental processes — or mind — and the physiology of our brain is something we’ll be studying for centuries, really," Presti tells me in his UC Berkeley office. "The brain is complicated. The more we learn about it, the more complicated it is."

My eyes wander across the piles of scientific books and papers on his desk

to the colorful East Indian paintings on his wall. My eyes settle on the

white bucket in the corner, and I marvel again at marveling. When my mind

notices my brain’s lack of focus, I decide I should take up

meditation. ![]()

The Probing Mind of the Dalai Lama

Science’s interest in Buddhism is matched by Buddhists’ interest

in science. The Tibetan Buddhist leader, the Dalai Lama, is particularly

interested in combining science and philosophy, as outlined on the website

for his organization, the Mind and Life Institute.

The Dalai Lama encourages rigorous scientific investigations into meditation. He believes Buddhism and science share the similar goals of obtaining knowledge about the world and alleviating human suffering. Just as he enjoys taking apart and tinkering with clocks, movie projectors, and other mechanical objects, he believes that uncovering the underlying mechanism of the brain is an interesting venture. When scientists ask what he would do if science ever contradicted Buddhist philosophy, the Dalai Lama responds that he would change the philosophy.

Despite his appreciation for what modern neurobiology has discovered about the brain, he does not feel that the physical brain of neurons and neurochemistry will ever tell the whole story. "While I agree with neuroscience that gross mental events correlate with mental activity," he writes in the magazine New Scientist, "I also feel that on a more subtle level of consciousness, brain and mind are two separate entities."

The Dalai Lama gathers Western neurobiologists, philosophers, and psychologists for discussions to his home in Dharamsala, India. In 1987, he co-founded the Mind and Life Institute, which encourages interaction and discourse between Buddhists and scientists. The institute funds and collaborates with scientists from many universities, including the University of Wisconsin at Madison, the University of California at San Francisco, the University of California at Berkeley, and Harvard University. These fruitful collaborations are translating the observations of Buddhist philosophers into the language of science.

"He’s a brilliant man," says UC Berkeley neurobiologist

David Presti. "He has really good ideas. He is fostering a dialogue

between science and Buddhism that began more than 15 years ago with the

Mind and Life conferences. I really don’t think, at this point, that

science is going to have that much to give to Buddhism, but I think

Buddhism is going to have a lot to give to neuroscience." ![]()

ABOUT THE WRITER

Raven Hanna

Raven Hanna

B.A. (biochemistry/molecular biology), UC Santa Cruz

Ph.D. (molecular biophysics & biochemistry), Yale University

ABOUT THE ILLUSTRATORS

Russell House grew up in Alabama, not far from mountains and miles of forest. He was taught to appreciate nature from his earliest memories. He was fishing as soon as he could hold a pole, hunting as soon as he could hold a gun and drawing as long as he can remember. His mother and father kept him outdoors and active. They nurtured his curiosity. His father taught him a respect for ecology and the balance of nature while his mother encouraged his budding artistic inclinations. When he started college he left art by the wayside. After two biology degrees and embarking on a Ph. D. in geology, the call of art led him to illustrate for his colleagues’ publications. He remembers working on an illustration (neglecting his own research) and saying aloud, “I wish I could draw like this every day of my life”. Now he can’t imagine doing anything else.

Victoria Fortune grew up in a graphic arts studio, and as an only child, amused herself with her drawings and her imagination. Art was later put aside as a “hobby” in order to pursue a career in something “more reliable”. She had always loved learning about nature and science and thought that was the way to go. While in college, attempting a degree in biology, she discovered the program almost by mistake. She was taking a much desired break from chemistry homework, and had wandered down the hall and into the Science Illustration department (as if guided by mysterious angelic voices). There, she met Jenny Keller, who answered many of her questions and set her on course. The blending of science and art was a perfect fit, and Victoria remains as enthusiastic about Science Illustration now as she felt that day. Victoria Fortune graduated from the University of California Santa Cruz in 2004 with a degree in Environmental studies. She was accepted into the graduate program in Science Illustration at UCSC the following fall.