The bottom land stretching from San Francisco to Sacramento is amazingly flat, a lake of earth. For 50 miles, it rises and falls no more than 25 feet. But every few miles, a ridge of rock and earth rises up, and at the top of the hump, shimmering and glistening, is water – a river, hovering above the land. The second-floor windows of a farmhouse are level with the rippling watercourse, with only a dirt levee keeping the water from spilling in.

Rocks creak underfoot, deep inside a seam in the earth’s crust.

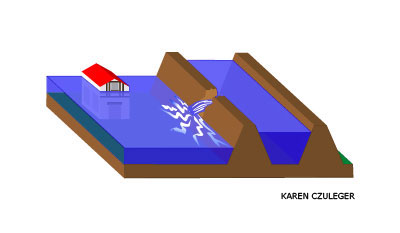

Scientists have warned for years that a large earthquake could shake these levees to rubble, releasing a cataract of water across the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta. And this flat ground isn’t just lower than the rivers – it's lower than the ocean. The unleashed rivers would suck seawater in behind them, creating a huge inland sea.

The destruction would ripple throughout California. Huge pumps draw fresh water from the Delta and send it to the taps of 23 million California homes and the sprinklers of farms throughout the Central Valley. Nearly half the nation’s fruits and vegetables grow in the Central Valley, nourished by Delta water carried through the huge aqueducts. If the sea comes rushing in, the pumps will suck saltwater. Engineers will flip off the switches, and the aqueducts will run dry.

Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger declared a state of emergency February 24, suspending state environmental laws to speed repair of the most fragile levees. Geologist Jeffrey Mount of the University of California at Davis says the Sacramento River Delta has a 2-in-3 chance of catastrophic levee failure in the next 50 years. Everyone in the Delta seems to repeat the same adage: “There are two kinds of levees: those that have failed and those that will fail.” Of many proposed solutions, none satisfies engineers and ecologists, farmers and suburbanites, Northern Californians and Southern Californians. But everyone agrees on two things: Something has to be done, and whatever it is, it’s going to cost a lot of money.

One hundred fifty years ago, the Delta was a vast, flat marshland where the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers met to battle the ocean. Freshwater flowed out and saltwater pushed back in, forming a huge nursery for fish and a feasting ground for migrating geese and pelicans. Salmon glutted the narrow Carquinez Strait as they fought their way upstream. Leaves and grasses fell into the water faster than they could rot, mushing down into rich, spongy peat.

When the Gold Rush waned, failed prospectors looked toward the wealth locked in the Delta’s fertile soils. Plentiful, cheap Chinese laborers piled the waterlogged soil into wheelbarrows to form rough levees, keeping the tides and spring runoff from washing across the fields. Over the next 70 years, farmers turned the entire marshland into islands divided by restricted waterways in much the same formation they are today, ultimately forming 1,100 miles of levees.

The problems of building with peat quickly became clear. As it dried, the partially decomposed plant matter rotted and shriveled and cracked. The fierce Delta winds blew it away. The ground sank and the levees shrank. The islands became anti-islands, bowls of land below sea level. Laborers with wheelbarrows couldn’t keep up, so steam-powered dredges began piling the soil higher and higher.

As the ground below the levees squished away, more earth was loaded on top. Backhoes piled up rock to armor the insides of the levees against the erosive wind-blown waves. Trucks carried in more solid dirt to widen the levees’ bases. But the levees are now basically what they were in 1850: piles of dirt.

Those piles barely restrain the rivers in a year without floods or earthquakes. The strain became clear one June morning in 2004, when a levee at the Jones Tract in the Central Delta simply gave way. Most likely, a beaver was remodeling its den inside the levee when it met up with a ground squirrel’s tunnel on the other side. A trickle of water seeped from one passageway to the other, carrying a bit of dirt along. The trickle turned into a gush, and soon the water churned over a 60-foot gash in the levee.

If flood fighters catch such breaks before the levee gives way, they can repair it by dumping on loads of dirt. But at the Jones Tract, the water had already smashed through the top of the levee, and the current washed away anything dumped in its path. Emergency crews had to wait until the entire sunken island filled up to sea level and the current slowed.

Rudy Mussi, a family farmer on the Jones Tract, lost $12 million that summer morning, including his four-year-old asparagus plantings that had just matured. He’d just finished paying off the debts from the last flood, seven years earlier. “After the realization goes by that we couldn’t win the flood fight, it’s just basically acceptance,” he says. “You know that the water is going to end up 20 feet high, and you just try to move as much equipment and as much fuel and fertilizer and belongings as you can.”

The riverbed is so flat that water flowed upstream and through the break. Seawater followed up the watercourse. The island filled for days. Once it had filled, trucks spent 30 days filling the gap with dirt, and for six months afterward, pumps sucked noisily at the intruding water and lifted it back into the riverbed.

Damage from the break cost $100 million – and that was only because the flood-fighters got lucky. Jones Tract had become a 17-square-mile lake. Wind churned the water into waves crashing against the next levee – against the side without rocks, the side that ordinarily is dry. The waves ate away at the dirt, working their way toward filling the next island, but the emergency crews fought back by piling up rocks. After three days, the flood fighters won, but it was “a close call,” Mussi says. If the levee had fallen, one levee after another might have succumbed to the surging water.

“You would have had water up to the doorsteps of Stockton,” Mussi says. “It was a shock because it happened in June. It wasn’t like it was in December with the storms and all that.”

Jeffrey Mount wasn’t surprised though. A geologist and director of the UC Davis Center for Watershed Sciences, he was a member of the State Reclamation Board, which oversees the levees, when the break happened. He had been predicting problems for a long time – and not just from enterprising beavers.

Suppose it were late January and a warm tropical storm arrived after snow had built up in the mountains, followed by another and then another. The entire snow pack would rush downstream with the rain. As many as 20 levees could fail, Mount worries, not just one. That might not happen for decades, but when it does, it will change the Delta forever, he says.

Mount predicts that the Delta would face a terrible shortage of manpower and machinery. Northern California has only one contractor equipped to repair a levee from barges. Others can work from trucks, but trucks don’t carry enough rock and can’t reach every break. Despite their best efforts, Mount says, the water would spread.

Still, problems for the water supply wouldn’t begin until the summer, when the rivers slow down. Ordinarily, the narrowness of the Delta’s waterways increases the force of the fresh water pushing against the tides. But with the rivers spread out across all the flooded islands, the tides would drive much further inland. Salt would spread deeply into the Delta, reaching the pumps and forcing engineers to shut them down.

Not everyone agrees with Mount’s assessment. David Mraz, flood manager at the California Department of Water Resources, discounts the likelihood that a large flood would disrupt the water supply. Floods only happen in the winter, and by definition they happen when the freshwater flows are high, keeping the salt water away. Mraz is confident that the levees could be repaired before the summer dries up the fresh water and the salt water intrudes. “It’ll be a huge effort,” he says, “but I think it’s reparable.”

Mraz administers a state program that assists farmers in improving the levees on their land, reimbursing up to 75% of the cost. Since large-scale flooding in 1986, the state has spent more than $200 million to bolster the levees. The flood-fighters point with pride to their successes maintaining the levees despite what they view as a shoestring budget.

Doing this on a bigger, more organized scale is the answer, some believe. A 1986 standard calls for raising and strengthening the levees to withstand a once-a-century flood, which would require $1 to $2 billion dollars. “We need to get the money into the dirt,” says Chris Neudeck, an owner of the Stockton engineering firm Kjeldsen, Sinnock and Neudeck, which has worked extensively on the levees. “The problems in the Delta can be solved. If you give me the right tools and the right amount of funds, we can move a lot of dirt, and that dirt serves its purpose pretty well.”

But Mount says that even a billion or two won’t be enough to solve the Delta’s problems. Each year the ground in the Delta sinks another inch or two, while global warming slowly but inexorably raises the sea level. Meanwhile, high in the Sierra Nevada, increasingly rain is falling instead of snow, and the rain runs off the mountains in a rush instead of melting gradually in the spring. Current standards don’t account for these changes, and over the long run, Mount says that they will add billions more to the bill.

And then there are earthquakes. Mraz may be sanguine about handling floods, but he’s not so optimistic about earthquakes: “An earthquake could really cause a lot of problems.” Mount is characteristically more dramatic. “If you have an earthquake, with multiple levee failures, it’s a mess. It’s breaking all over the place.”

A state study completed in 2000 concluded that a magnitude-6.5 earthquake on the Coast Range-Central Valley Fault running through the Delta would destroy around 20 levees. The cost of such an earthquake would be between $5 billion and $30 billion, according to a 2005 report for the Department of Water Resources. By comparison, the cost of all the property damage from San Francisco’s 1989 earthquake was $7 billion ($11 billion in 2006 dollars). The chance of such an earthquake occurring in any particular year is quite low – around a third of a percent. But over time, it’s a certainty.

“You would end up with so much flooding that you might never recover,” says Les Harder, chief flood manager for the Department of Water Resources. “That’s a rare event. I probably won’t see it in my lifetime. But that chance was about the same as the chance for Hurricane Katrina – New Orleans just ran out of luck sooner.”

Earthquakes can turn seemingly solid soils to mush. When wet sandy soils are shaken, the lowest layers of the sand compact, pushing the water higher. There it mixes with the sand into a quicksand-like slurry. The levees have layers both below and within them that could liquefy, making them both sink and slump like melted ice cream.

To protect the levees against earthquakes, engineers would dramatically widen them using a mix of sand and clay that won’t shrink or liquefy. This would trap the soft soil of the existing levees to keep it from slumping outward and provide a broad enough cap that the toothpaste-like peat and sand underneath would have nowhere to go. Retrofitting the entire system this way would cost as much as $10 billion, Mraz estimates.

Even setting aside that startling cost, there’s another downside. If the state builds huge levees, the temptation to build houses behind them would be overwhelming. Land behind a levee strong enough to withstand a 100-year flood is removed from the official flood plain, making houses on it eligible for a mortgage without flood insurance. Each year, California’s population grows by a half million people, and the pressure from that growth is already being felt in the Delta. Every few blocks on Route 4 in Brentwood through the heart of the Delta, a person stands wiggling a sign shaped like an arrow, directing attention to a new development with units for sale. And 130,000 more homes are proposed.

If water pours into housing developments, a true New Orleans-style disaster could unfold, with vastly higher financial and human costs. Because Hurricane Katrina hit an urban area, rather than farmland, the cost is expected to exceed $100 billion and 300 lives. Mount seethes at the prospect of development in the Delta. “That’s dumb growth, not smart growth,” he says. “For the sake of the future of California and its relationship to the Delta, we should not be building homes in the Delta. We just flat should not be doing it.”

Mount’s conclusion is that the levees alone aren’t enough to protect the water supply. Even if California were to spend billions to make the levees resistant to earthquakes and floods, it would have to keep spending to maintain them while the ground sinks, the ocean rises, and the rains fall.

So Mount says California had better give some hard thought to what it’s willing to give up in the Delta. One possibility would be to allow some islands to flood, making fewer miles of levees to defend. The less sunken areas at the edges of the Delta – precisely the areas slated for development – would return to tidal marsh, alleviating a bit of the ecological pressure on the Delta. But biologists are unsure what the ecological impacts of restoring the marshland would be. Moreover, making land off-limits to development would drive up housing prices. And farmers aren’t exactly lining up to have their land inundated.

An alternative proposal would create a water supply system that bypasses the Delta entirely. In this scenario, fresh water from the upper reaches of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers would be piped straight to central and southern California. This solution was proposed in the 1980s as the “Peripheral Canal,” but voters soundly defeated it. Northern Californians worried they would lose control of their water, and ecologists fretted about the impacts to the Delta. But Mount and other experts say now may be time to revisit the idea.

Mount has also proposed building large reservoirs south of the Delta to supply the California aqueduct if water at the pumps were to get salty, buying time for earth movers to do their work. That suggestion hasn’t yet passed beyond the brainstorming stage.

The problem with all of these ideas is that although it is very likely the levees will fail catastrophically within fifty years, Mount says, it is quite unlikely they will fail tomorrow. And the real disaster – a major earthquake – may not happen in any of our lifetimes. The most recent proposed California budget adds $35 million for levee improvements – not even close to the one to ten billion necessary to begin to solve the Delta’s problems.

The tragedy in New Orleans may prove to be a blessing in the Delta. California lawmakers have awakened to the danger, and the governor is trying to raise billions of dollars from the federal government to help. It remains to be seen whether any money raised will be spent on trying to maintain things as they are or whether the state will make the hard choices necessary to develop a realistic long-term plan for the Delta.

And those hard choices will have to be made on the basis of calculated long-term risks that seems to carry little emotional weight for the people living in the Delta. One fisherman commented that wherever you live, “It’s always something. If it’s not the levees, it’s hurricanes or it’s tornadoes or it’s wildfires.” The Delta farmers and fishermen live with the levees every day, and most of the time, they seem to do their job pretty well. It’s hard to fathom that there really could be a problem vastly worse than what they’ve experienced.

So the farmer in the two-story farmhouse will continue to till his fields,

maintain his levees, and watch for beavers. The water outside his

second-story window will rise and fall as the tides push it in and out

twice each day. His asparagus will grow, and he’ll keep trying to pay

off his debts and buy a new truck, before the next flood comes.

![]()

ABOUT THE WRITER

Julie Rehmeyer

B.A. (mathematics), Wellesley College

M.S. (mathematics), Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Internships: UC Berkeley alumni magazine, Science News

I've always had a strong drive to understand things deeply and make sense of them for myself. I was drawn to math because its precision allows you to understand things very deeply indeed.

But my curiosity roamed beyond the edges of mathematics into the murkiness of the real world. So I moved into teaching the classics at St. John's College, reading Plato, Shakespeare, Bach and Newton, confronting the fundamental questions the books raise. What is virtue? How can math say anything about the physical world? Why does music move us? I also built my own house, doing most of the work myself.

Now, at age 32, I'm ready to leave academia entirely to confront the real world in all its messy glory, and to see if in making sense of it for myself, I can make sense of it for other people too.

ABOUT THE ILLUSTRATORS

Erika Beyer

B.A. (geology), Carleton College, Northfield, Minn.

Erika Beyer first heard about the Science Illustration program in 1999 from

a professor at Carleton College. It took her the next six years, several

desk jobs, two bike tours, and one mural to arrive in Santa Cruz. The more

time Erika spent in the work world, the more she realized that the most

rewarding profession would be one that combines two of her passions:

science and art. She is excited to return to Oregon and begin illustrating

a book of botanical subjects. Please visit her website at

http://www.erikabeyer.com/.

Erika Beyer first heard about the Science Illustration program in 1999 from

a professor at Carleton College. It took her the next six years, several

desk jobs, two bike tours, and one mural to arrive in Santa Cruz. The more

time Erika spent in the work world, the more she realized that the most

rewarding profession would be one that combines two of her passions:

science and art. She is excited to return to Oregon and begin illustrating

a book of botanical subjects. Please visit her website at

http://www.erikabeyer.com/.

Karen Czuleger

B.A. (biology and environmental studies), University of California, Santa

Cruz

From the coastal redwoods of Santa Cruz to the rocky slopes of Catalina

Island, Karen has lived in places of beauty. Observing life in her own

backyard inspired her decision to major in the sciences as an

undergraduate. It was through detailed illustrations of subjects in her

plant physiology class that she found the perfect blend of science and art.

After college she worked and traveled along the Pacific coastline. She

settled down as educator on Catalina Island where she used science

illustrations to simplify complicated subjects to children. It was there

that her awe for the ocean reawakened her love for art and the desire to

pursue scientific illustration.

From the coastal redwoods of Santa Cruz to the rocky slopes of Catalina

Island, Karen has lived in places of beauty. Observing life in her own

backyard inspired her decision to major in the sciences as an

undergraduate. It was through detailed illustrations of subjects in her

plant physiology class that she found the perfect blend of science and art.

After college she worked and traveled along the Pacific coastline. She

settled down as educator on Catalina Island where she used science

illustrations to simplify complicated subjects to children. It was there

that her awe for the ocean reawakened her love for art and the desire to

pursue scientific illustration.