MDR pumps don't always work to benefit the

organism. They can bestow deadly power in the form of resistance to

antibiotics to harmful bacteria. While bacterial MDR genes are not

identical to those from mollusks and people, the three-dimensional shape

of all pumps is much the same, and all MDR pumps perform a similar task:

preventing potentially harmful molecules from setting up shop inside their

own quarters, the cell's interior.

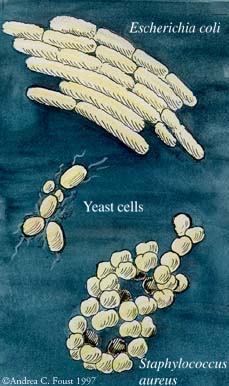

Microbiologist Kim Lewis of the University of Maryland at Baltimore,

studies MDR pumps in so-called "gram-negative" bacteria, a group

of microbes that includes the recently notorious E. Coli. One member of

this microbial family, S. aureus , can skillfully evade antibiotic-containing

hospital handsoaps by immediately rejecting their antiseptic weaponry. This

renders the drugs useless, and worse, can lead to menacing and sometimes

deadly infections. "It's a pretty dangerous pest," says Lewis.

Many MDR-like pumps also confer resistance against first-line drugs used

to treat pathogenic yeasts and parasites, says Lewis. Resistance to drugs

called antifungals that are used to treat yeast infections is increasing

rapidly, in particular affecting immune-crippled AIDS patients, who can't

fight back, he says. And the latest victim that may succumb to MDR is saquinavir,

one of a class of anti-AIDS drugs called protease inhibitors, a recent study

suggests. Some bacteria, such as P. aeruginosa, which causes an uncontrolled,

life-threatening infection called sepsis, have a virtual armamentarium of

different MDR pumps. "They extrude practically every [drug] we know

of," says Lewis. |

|