ANTHROPOLOGIST

Robert Franciscus of Stanford University has been studying the Neandertal

face for more than a decade, trying to understand its unusual architecture.

He specializes on the nasal and facial anatomy of Neandertals, and

on what we can learn about human evolution from them. (To his embarassment,

a colleague approached him at his first scientific conference and

said, "Hey, you're the nose guy!") To fathom why Neanderthals had

this combination of features, Franciscus says you need to look at

what Neandertals did with their mouth--besides eat.

Although Neandertals manufactured a wide variety

of stone tools, from heavy hand axes to delicate blades, the mouth

was a key supplement to their tool kit. From microscopic grooves

and wear patterns on Neandertal teeth, scientists conclude that

the mouth doubled as a vise for gripping the end of a stick while

the hands shaped the other end, and as a tanner's mallet for softening

and working animal skins. Straight scratches on the front teeth

suggest that Neandertals held food in the mouth while cutting it

with stone tools. Continual heavy use gradually eroded the teeth,

so that "by the time Neandertals reached their late 30s and early

40s, their teeth were worn down to essentially nothing," Franciscus

says. Only smooth nubs projected beyond the gumline.

Hard, frequent biting may have created another,

more serious problem: strain on the facial bones. According to anthropologist

Yoel Rak of Tel Aviv University, the Neandertal face represents

an evolved solution for dissipating this stress. Over many generations,

he says, the bones of the face and jaw became thicker and larger

in response to the strain from biting. This shoved the face forward.

Rak likens the Neandertal face to a pair of swinging doors that

had been pushed partway open. His hypothesis, which he set forth

in a 1986 paper, also explains the large Neandertal nose: as the

face got bigger, the nose enlarged along with it, just as a nose

painted on a balloon would grow as the balloon filled with air.

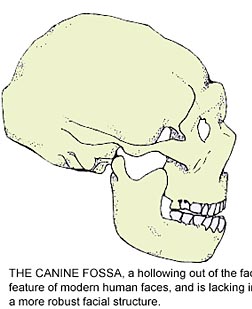

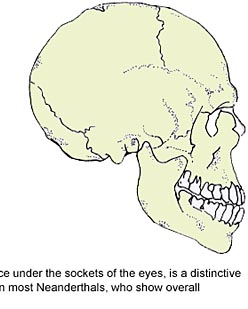

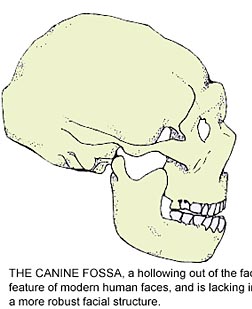

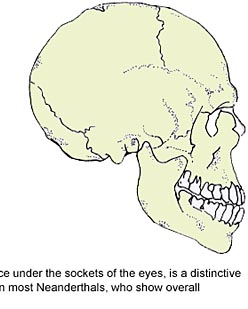

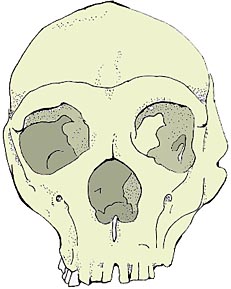

One skull feature to which Rak called attention

is the canine fossa, the hollow just below the human cheekbone.

It's absent in Neandertals. (No Neandertal could ever achieve the

sunken-cheeked, fashionably starved look coveted by today's models.)

Instead, a wall of bone continues straight down to the teeth--an

arrangement Rak claimed strengthened the upper jaw.

However, Franciscus points out one implausibility

in this adaptive story. For natural selection to favor a stronger

face, weaker-faced Neandertals must have paid some penalty in survival

or reproduction--say, they often fatally shattered their skull while

working a stick or gnawing a skin. If Neandertals--or their ancestors--did

regularly suffer this kind of injury, the fossil record shows no

trace of it.