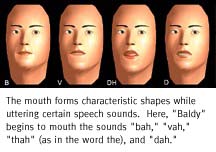

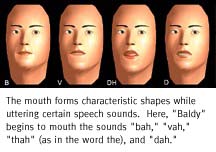

Some sounds do appear distinct on the lips, such as the "th" sound in "the," where people stick their tongues out to produce the sound. Others look too similar on the lips for easy reading, such as the pursed lips used to produce the "m" and "b" in "mah" and "bah," and the mouth shape to begin saying "tah" and "kah."

There's more to lip-reading than checking out lip movements, though. Someone who's reading your lips might catch the tongue action involved in saying "tah" to distinguish it from "kah," for example. In fact, lip-reading is often called speech-reading instead.

Psychologist Larry Rosenblum at the University of California, Riverside, heads one of the labs studying which facial clues matter during lip-reading. He does so by asking people to observe the speech of someone wearing 13 reflective dots on their darkened face. When the dot-wearer stands against a black background, the viewer can't see their face at all -- just the dots as "a constellation of stars," Rosenblum says. The viewer then tries to connect the dots to the speech while the subject speaks into a background of noise like that found between channels on a radio. Rosenblum has found dots on the chin, cheeks, and nose add little to a viewer's understanding of speech; dots on the teeth and tongue, however, make it noticeably easier to understand what's being said.

Experienced lip-readers draw on other tools as well. Bill Brawner says, "I don't just read sounds, I read words as units -- even whole phrases." And he's always looking for other clues, the facial and body language moves used to express meaning.