|

| Illustration: Jenna McGuire |

Naturalists are retracing century-old studies of fragile life in the harsh desert. Emily Benson follows their path. Illustrated by Jenna McGuire and Monica Jurik.

Cool damp air rises from the spring, a trickle of water dripping from a rusted pipe surrounded by pale concrete and bedrock. Above the pipe, patches of last season’s desiccated reeds mark spots where the water creeps close to the surface of this desert canyon on the edge of Death Valley National Park.

Neon-bright orange and pink ribbons bloom across the hillside and valley floor like wildflowers. They mark the locations of metal traps, each one the size and shape of a brick, set by biologist James Patton here at Upper Emigrant Springs. Patton reaches down into a rocky crevice, retrieves one, and dumps its contents into his hand. It’s a sleepy ball of fluff the size of a tangerine—a baby desert woodrat, just a few months old.

The rodent, eyes closed, emits a low-pitched peep as it falls into Patton’s palm. A red pinprick of a flea leaps from its ear onto Patton’s thumb, then ricochets off into the dry desert scrub. Patton studies the woodrat, then gently lets the creature go in the cool air underneath the rock overhang, protected from hungry raptors and the rising late-morning heat. He pulls a memo pad from his breast pocket and scribbles a few notes.

Famed naturalist Joseph Grinnell visited this same spot one April day in 1920. He camped in this canyon, setting out mouse and rat traps below the spring by moonlight. Today, a new generation of biologists is retracing Grinnell’s steps here, and across California.

Starting in the early 1900s, Grinnell and his collaborators traveled the length of California by narrow-gauge railroad, Model T Ford, buckboard, burro, and on foot, chronicling their journeys with notes and maps. Among splotches of ink and blood and crushed beetles, they documented the state’s natural places, in as much detail as they could muster. They wrote about the ravens they watched, the canyon mice they captured, and the desert springs they camped beside.

Their field notebooks, crammed into glass-front bookshelves, now line a seminar room at the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology at UC Berkeley. “Most field collectors maintain notebooks of some kind, but Grinnell really established the doctrine of recording the detail contained in those books,” says Patton, a professor emeritus who collects and curates small mammals for the museum.

The world, and California’s deserts along with it, has changed in the nearly 100 years since Grinnell filled his notebooks with details of Death Valley’s wildlife. But ecologists still seek answers to the same questions: What creatures live in the cracks and crevices of the desert cliffs? Are they adapting to their changing environment? Thanks to Grinnell’s foresight, modern researchers have a uniquely detailed baseline against which they can compare new surveys of the deserts. Today’s studies, they hope, will inform and guide tomorrow’s ecological quests as well—after another century of change has again transformed California.

“Do record them all!”

Grinnell, the museum’s first director, kept track of the animals he collected, but he also logged additional details of their capture. His extensive records included observations like the names of the plants surrounding a successful trap. His team’s early 20th century description of Yosemite National Park and its surroundings, for example, consists of thousands of pages of field notes and hundreds of photographs.

“Grinnell’s notes are particularly remarkable because of their structure, depth of detail, and the context that they provide, both historical and ecological,” says Carolyn Sheffield, a librarian and field notebook expert at the Smithsonian Institution.

|

Emily Benson goes inside the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology at UC Berkeley, where archivist Christina Fidler explains how to care for century-old notes and specimens. Click on image to play. |

Many vertebrate biologists today follow this “Grinnellian method” for taking field notes. Each entry includes the same elements: A log of the day’s activities follows a list of creatures encountered, and a summary of observations related to each species concludes the account.

Grinnell’s descriptions range from terse statements (“Two Texas nighthawks over alfalfa”) to revealing glimpses into his disposition. In 1917, after listing the birds he saw that day, Grinnell described a small Death Valley pond as an “oasis in the desert like an island in the sea; what a station for continuous observation of migrations thruout the year! Put someone here, to see what comes thru this north-and-south trough! No other place in North America like it!”

The museum naturalists slipped maps, photographs, and sketches of rodent burrows between the handwritten pages. Because of the notebooks’ specificity, scientists like Patton can mine them for the data they need to identify changes in a place like Death Valley across decades.

Grinnell could not have anticipated modern climate change or the way it is transforming the planet. But he did understand that through activities like ranching and farming, people influence ecosystems. In a 1923 letter, he described the decimation of several species in the northeast corner of California. Human settlement was responsible, he wrote. “And no telling how many smaller mammals and birds are doomed,” he added. What Grinnell witnessed convinced him of the vital importance of recording current conditions before they could change even further.

“You can’t tell in advance which observations will prove valuable,” he wrote in 1908. “Do record them all!”

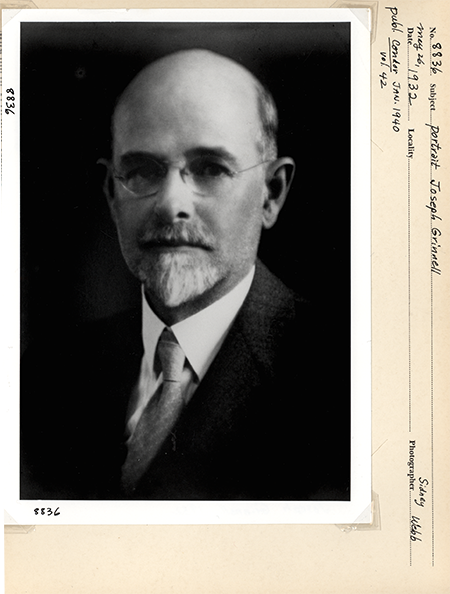

A black-framed portrait of Grinnell hangs in a hallway outside the room housing the museum’s field notebooks. He’s wearing a dark suit over a crisp white shirt, the edges of the collar sharp against his neck. He seems to gaze directly at the viewer through his wire-rimmed glasses, as if studying another specimen in the field.

|

Photo courtesy of UC Berkeley Museum of Vertebrate Zoology |

| Naturalist Joseph Grinnell in 1932. |

|

You can almost imagine him pulling out a notebook as you walk away, noting the time and circumstances of the encounter, just as he did with a kit fox in the middle of the night in Death Valley. “The animal was in no way alarmed, looked up once or twice, nosed along the ground, then trotted off into the gloom,” Grinnell wrote. “Once I saw a glowing pink eye shine.”

Underneath the portrait, another picture frame holds a passage that Grinnell authored in 1910: “I wish to emphasize what I believe will ultimately prove to be the greatest value of our museum,” he wrote. “This value will not, however, be realized until the lapse of many years, possibly a century, assuming that our material is safely preserved. And this is that the student of the future will have access to the original record of faunal conditions in California and the west wherever we now work.”

“We were that student of the future,” says UC Berkeley conservation biologist Steven Beissinger.

The work that counts

More than 230,000 mammals reside in the museum’s collection. Reptiles, amphibians, and birds from all over the world round out the holdings. In the osteology room, metal shelves hold rows of skulls. Here, an embryonic hippo; there, a Steller’s sea cow.

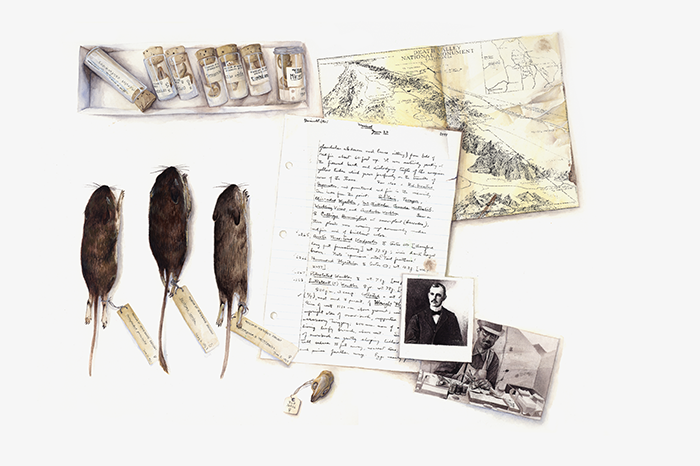

The deer mice, woodrats, and other similarly small creatures occupy dozens of gray metal cabinets stacked under low fluorescent lights. Open one, and several shallow drawers come into view. Nestled here are the skulls and skins of the specimens Grinnell gathered in Death Valley, and all the others collected since then.

Their preparation begins in the field. “You just peel the body out of there,” Patton says, stuff the skin with cotton, slide wires down the legs and tail, then pin it out on a board until it dries. He brings the bones back to Berkeley for cleaning—with the help of a colony of flesh-eating insects.

|

| Illustration: Monica Jurik |

Research assistants prepare the skeletons in a laboratory that smells of recent death, sweet and rancid. Inside a glass terrarium, six rodent skulls rest within alternating divots of an egg carton. Dermestid beetle larvae scramble over the bones, weaving in and out of eye sockets delineated by threadlike cheekbones. “If the bugs are hungry, you can clean a skull overnight,” Patton says.

Patton and his colleagues are carrying on the work started by Grinnell in 1908, the year naturalist Annie Alexander founded the museum. The researchers wanted to form a collection, but they also were dedicated to meticulously recording data to make the specimens useful. “Work systematically and intelligently carried on is the work that counts,” Alexander wrote.

Pushed by climate change

Those records allow modern scientists to compare 100-year-old inventories to current ones, according to Patton. When he examines the logs from a team’s field expedition, says Patton, “I need to know where they were, I need to know what they caught, and I need to know what kind of effort they put in.”

Gauging those efforts—how many traps they set, and how long they left them out—helps researchers make valid comparisons today. For instance, Patton might catch twice as many long-tailed pocket mice as Grinnell did in the same spot. Because Grinnell logged the specifics of his traps, Patton can figure out whether the pocket mice population actually doubled—or just the effort it took to catch them.

Grinnell and his coworkers also recorded the elevation where they captured individual critters, which not every naturalist of the time did. That detailed information gave Patton and his colleagues an idea.

From 1914 through 1920, Grinnell and his team surveyed a swath of ground from California’s Central Valley up over the Sierra Nevada and through Yosemite National Park. The transect began at 200 feet above sea level and extended 10,000 feet higher. Within that range, different species of small mammals tended to appear at different elevations, each one suited to living in that regime.

In the century since Grinnell’s survey, the average minimum temperature each month had gone up by 6.7°F. That can be a problem for animals adapted to cold alpine climates, like American pikas, which overheat and die if they can’t find a place to cool off during hot summer days. Had some creatures crept higher up Yosemite’s slopes, trying to remain within their preferred cooler climes? To find out, the scientists revisited the same field sites to survey the residents.

Of the 28 small mammals the researchers studied, from voles and mice to marmots and kangaroo rats, half had expanded higher into the mountains. Scientists worry that some creatures living near the tops of mountain peaks might soon run out of room. The species that shifted upward lived an average of 1,500 feet higher than where Grinnell had observed them. The scientists say Earth’s warmer temperatures pushed them there.

|

Author Emily Benson narrates a slideshow of past and present images of research in Death Valley National Park. Click to play slideshow. |

The same desert ground

The UC Berkeley resurvey team submitted its final report on the changes in Yosemite in 2007. But Grinnell had roamed across the entire state. Now, Patton and his colleagues are following him once again—this time, to the desert.

Their near-term plans focus on the Mojave Desert, including Death Valley, where the average temperature has risen by 1°F since Grinnell’s day. Just a few degrees more, scientists say, and the ecosystem might change irrevocably. “Species are living on the edge there,” Beissinger says.

At a campground in Death Valley, six miles below Upper Emigrant Springs, Patton sifts through a binder he’s made of excerpts and photographs from earlier expeditions. Images, notes, and maps with routes and trapping sites traced in pencil help Patton figure out exactly where Grinnell and other naturalists went. One sepia-toned photograph taken by a student in 1917 shows a rudimentary dwelling created by a cave mouth shored up with piled stones. Today, the stone wall is gone but the distinctive cave remains, its ceiling still blackened by countless campfires. The nearly century-old snapshot confirmed that Patton was sampling the correct set of springs in Emigrant Canyon.

“It’s not too difficult to put your feet on the same piece of ground that they put their feet on,” Patton says.

But Patton won’t use exactly the same methods. A century ago, collectors used snap-traps to catch small mammals—just like the mousetraps you might have under your kitchen sink—or a shotgun. Capturing creatures often wasn’t easy. On one Death Valley trip, Grinnell spent days looking for a species of ground squirrel that had eluded his traps. He finally shot one. Hearing another squeak a few feet away, he turned and the animal vanished, “quick as thought.”

Now, Patton mostly uses Sherman traps, hollow metal boxes that he and his wife Carol tuck below rock overhangs and under bunches of rabbitbrush at Upper Emigrant Springs. They fling a handful of bait—rolled oats and birdseed, carried in a ragged canvas sack slung over Patton’s shoulder—into each trap. They’ll walk the trap line in the morning and again in the afternoon for four days, checking for mice, squirrels, and other rodents. After that, they’ll move on to another part of Death Valley.

|

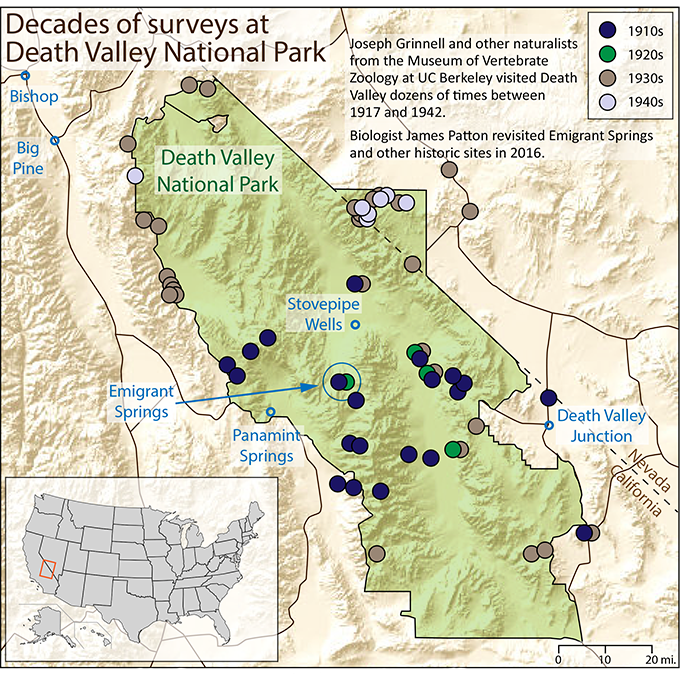

| Graphic: Emily Benson. Sources: James Patton/UC Berkeley Museum of Vertebrate Zoology & USGS |

Most of the time, Patton lets his quarry go. Sometimes, though, he keeps an animal to add to the museum’s collection. Preserved specimens allow researchers to answer certain questions, Patton says. For example: As California’s deserts continue to heat up, will the bodies of rodents adapt to the more demanding environment? To find out, scientists need to compare creatures from today to ones collected in the past.

Back at the campground, Patton transforms the back of his Toyota 4Runner into a lab. A full coffee cup and vials waiting for tissue samples sit atop a metal chest, and a sturdy cardboard box becomes a dissection table. Patton transcribes his field notes into a faded blue cloth journal held together by duct tape, adding measurements to the pages as he works on specimens. The loose-leaf, blue-lined sheets are the same size as the paper Grinnell used for his notes. Patton finishes stuffing a woodrat pelt with cotton, tosses it behind the vials, and takes a sip from his mug.

It’s important to track small mammals because they’re an essential part of desert ecosystems, Patton explains. Burrowing pocket gophers stir up soil, aerating and redistributing it. Kangaroo rats cache seeds underground, often leaving stashes that can later germinate. And all sorts of rodents provide food for larger creatures like snakes and kit foxes. “Everybody plays their role,” Patton says. It’s important to track small mammals because they’re an essential part of desert ecosystems, Patton explains. Burrowing pocket gophers stir up soil, aerating and redistributing it. Kangaroo rats cache seeds underground, often leaving stashes that can later germinate. And all sorts of rodents provide food for larger creatures like snakes and kit foxes. “Everybody plays their role,” Patton says.

Just before dinner, the Pattons head back up the winding canyon road to check the traps at Upper Emigrant Springs once more. Sometimes on quiet desert nights, James Patton says, he hears the wails of grasshopper mice, sitting up on their haunches and howling to mark the edges of their territory. But he finds no grasshopper mice this time. Most of the traps are empty, their intended targets having spent the heat of the day underground instead of scavenging for birdseed and oats. Carol Patton opens the hatch of a successful trap, and a pocket mouse slips out into the fading afternoon light.

“See you tomorrow,” James Patton calls to the mouse. It skitters across the ground, searching for a safe burrow hidden beneath the gravel of this desert canyon, folded into the rugged mountains ringing Death Valley.

© 2016 Emily Benson / UC Santa Cruz Science Communication Program

Top

Emily Benson Emily Benson

B.A. (behavioral neuroscience) Colgate University

M.S. (biology) University of Alaska Fairbanks

Internship: New Scientist (Boston)

The steady beat of waves lapping the lakeshore at dawn and the ethereal echo of loons wailing at dusk bracketed my childhood summer days in New York’s Adirondack Mountains. Over time, my love of water evolved into a desire to study the creatures beneath the surface. My scientific endeavors took me to Alaska, where I examined algae under both sunny and snowy skies, and to Idaho, where I monitored threatened trout amid the occasional buzz of rattlesnakes.

Throughout those adventures, I told my friends tales of fieldwork salvaged from bears and floods, or beavers and cattle drives, first with my voice and later with my pen. I realized I wanted to share stories of scientists struggling to illuminate the world’s natural rhythms. Lakes and loons, floods and trout—I’m ready to chronicle their chorus.

Emily Benson’s website

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Jenna McGuire

B.S. (wildlife biology) University of Guelph, Ontario

Internship: Parks Canada

Jenna grew up snorkeling shipwrecks and exploring caves in her hometown and has always had a love of nature and science. She has worked in the Canadian national parks system for more than a decade in the fields of research science and nature interpretation. She is passionate about communicating science and nature concepts to engage and inspire conservation, wonder and understanding. Her favorite subjects include botany, ichthyology, herpetology and invertebrate zoology and paleontology. Jenna loves to create images that tell a complex scientific story or reveal hidden worlds.

Jenna McGuire’s website

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Monica Jurik Monica Jurik

B.S. (art) Southern Oregon University

Internship: The Field Museum of Natural History (Chicago)

Monica is a natural science illustrator with a special interest in paleobiology. Having started out as an art student who branched into science illustration, she studied studio art and animation and moved on to the sciences. She got her start with entomology by helping to illustrate several smaller projects. With a love of dinosaurs and ancient creatures, she’s excited to continue her education with her internship at the Field Museum.

Monica Jurik’s website

Top

|