|

| Illustration: Kelly Lance |

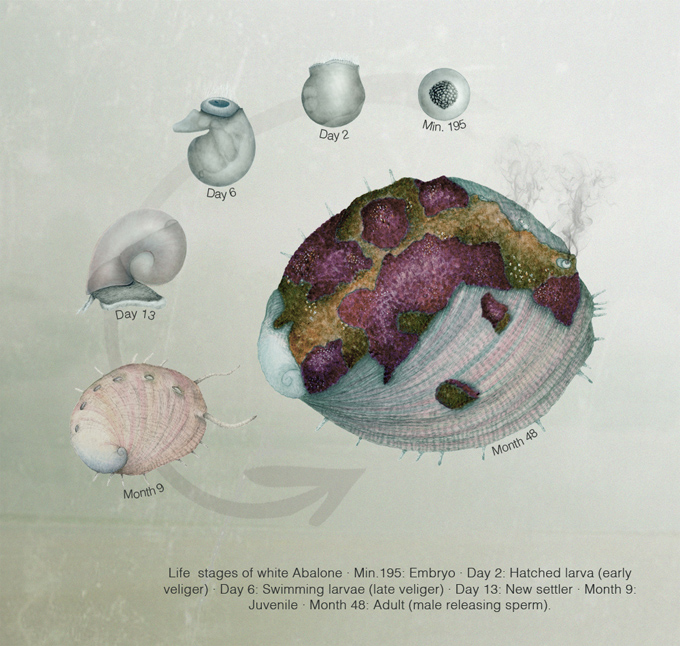

Scientists struggle to bring white abalone back from the brink of extinction, but time is running out. Ryder Diaz wades in. Illustrated by Kelly Lance and Carolina Rivera Alvarez.

A male white abalone soaks in a bucket of hydrogen peroxide. A fringe of long, thin tentacles peeks out from under his reddish-brown shell. The sea snail plants his muscular foot firmly against the bottom of the tub. Hydrogen peroxide usually puts an abalone in the mood to spawn, coaxing him to shoot sperm through holes in his shell. The bucket of clear liquid should turn a murky white. But all that emerges from this lonely snail is a small cloud, like a faint puff of smoke.

“They’re giving us all the gametes they’ve got,” says Kristin Aquilino, a postdoctoral researcher at Bodega Marine Laboratory, 60 miles north of San Francisco. For two years, Aquilino has traveled to labs and aquaria across California, where she has struggled to breed captive white abalone. The animals should spawn millions of sperm and eggs — but something is holding them back.

Intense fishing in the 1970s devastated white abalone populations. By 2001, the delicacy was the first marine invertebrate to land on the endangered species list. The few desolate animals that remain in the ocean are like islands, too far from a mate to reproduce. “We can’t leave the last male and last female and assume they’ll start all over again,” says Bodega Marine Lab director Gary Cherr. “It’s not Adam and Eve.” Intense fishing in the 1970s devastated white abalone populations. By 2001, the delicacy was the first marine invertebrate to land on the endangered species list. The few desolate animals that remain in the ocean are like islands, too far from a mate to reproduce. “We can’t leave the last male and last female and assume they’ll start all over again,” says Bodega Marine Lab director Gary Cherr. “It’s not Adam and Eve.”

Scientists must play matchmaker for white abalone to endure. But the timid animals won’t cooperate. Every year, more wild and captive abalone vanish, infected by disease and parasites or expired from old age. Now, after almost a decade of failed attempts, the first babies to survive in captivity munch on algae in Cherr’s laboratory. A small grey tub cradles the future of the species. But at the moment, there are only 24 of them.

This small band of snails is historic, but Cherr hopes it’s just a preview. In February 2013, he shuffled the lab’s group of adult white abalone into a new facility where he can tweak light and temperature. Cherr thinks he can boost each abalone’s stock of sperm and eggs if he can get the conditions just right. Bodega scientists already have managed to curb disease and parasites. In a few years, the researchers hope to return white abalone to the sea. But as the troop of captive adult abalone grows older, Cherr’s team is racing against time.

“If there’s not some sort of restocking out in the ocean in the next 10 years,” says Cherr, “they’re pretty much gone.”

Destined to die

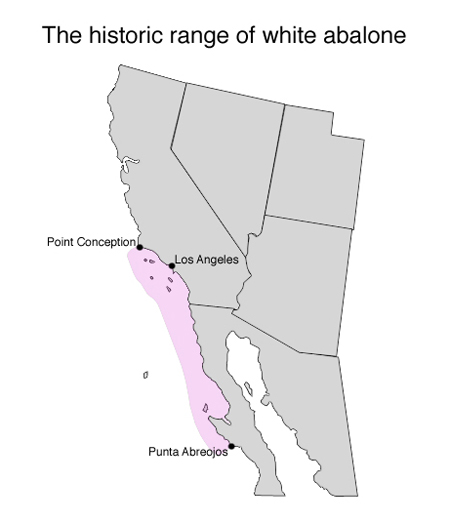

Early last century, white abalone nestled deep in the ocean and chomped on kelp and other algae, far from the pry bars and baskets of fishermen. Starting at Point Conception, near Santa Barbara, white abalone lived along an 800-mile strip of coastline that dipped down into Mexico. Southern California fishermen harvested species of abalone — the reds, blacks, and greens — that covered shallow rocks. Whites, the deepest-dwelling of all abalone, mingled out of reach in dense fraternities up to 200 feet deep.

|

Graphic: Ryder Diaz |

|

|

These large marine snails clung to rocks using their muscular orange feet like suction cups. Over their 30-odd-year lifetimes, white abalone twisted and rubbed their rough algae-coated shells into the rock’s surface, leaving behind marks of their persistence: oval footprint-like indentations. During the day, the creatures were quiet. In the shadowy nights, the congregation of abalone stirred. Snails reared up on their haunches and stretched outward, grasping for bits of floating algae to eat.

But by the late 1960s, their cover was blown. A new breed of divers donning SCUBA gear descended to greater depths to pry dinner-plate-sized white abalone off the rocks. “You could basically eat [them] right out of the water,” says Bruce Steele, a 40-year veteran diver. Other abalone flesh was tough, forcing processors to thwack three-pound oak mallets against the light-colored meat. But white abalone were instantly tender, says Steele.

Their reputation as the tastiest of California’s abalone — with a flavor similar to squid or a sweet oyster — may have risen because whites also were rare. Their fishery peaked in 1972, with 65 tons of animals landing on California docks, still just a fraction of other abalone numbers. By the late 1970s, all abalone became harder to find. When one patch dried up, fishermen moved to the next. “It wasn’t fishing as much as mining,” says biologist Tom McCormick, owner of Proteus Sea Farm in Ojai, California.

By 1979, the hauls of whites trickled to none. California ended all commercial abalone fishing in 1997. In a 2008 report for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), a group of scientists argued that 99 percent of the wild white abalone population had been lost since the 1970s. The remaining 1 percent were so isolated that each one might as well have been alone.

Every year, female white abalone can spurt three to six million eggs out of the holes in their shells, like tiny fountains. The eggs perch on nearby rocky shelves. A male must be within a cozy ten feet or so for sperm and egg to marry. But in most places along the California coast, abalone simply are too far apart.

“The population is already functionally extinct,” says Melissa Neuman, NOAA’s white abalone recovery coordinator. With every passing season, the animals grow older and disappear.

Something in the water

In 2000, scientists from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) collected a group of adult white abalone from the ocean. With a dozen of those snails, Tom McCormick spawned more than 100,000 juveniles by 2003. Reddish-white shells of endangered white abalone coated the walls of his tanks in Oxnard, fed by a constant stream of water from the sea. Then one warm summer, some animals began to die.

McCormick was used to the rhythm of death. He mixed buckets of eggs and sperm to create tens of millions of embryos. As with many species that spawn millions of children, most of them die. “You might lose 99 percent of them, but you’re still going to have an awful lot,” says McCormick. But the tempo of this death toll kept rising. Muscular bodies began to shrivel. They lost their grip on the sides of the tank, peeled off, and sank. Within a few months, thousands of empty shells piled up.

McCormick sent a sample to the Bodega Marine Lab, run by the University of California, Davis. The abalone tested positive for a bacterium that causes withering syndrome: a disease that killed throngs of wild black abalone but had never been seen in whites. Bacteria had flowed into the tanks with ocean water. In cold water, the white abalone were safe. But when the temperature rose above 64°F, the disease took hold.

The bacteria invade cells lining an abalone’s digestive tract. There, they multiply inside swelling masses, which eventually burst. Bacteria spews out and poisons nearby cells. Some hitch a ride out of the animal in feces, to be swallowed by another unlucky abalone.

Sick animals stop eating. “They are living off their big foot muscle,” says Jim Moore, a wildlife pathologist at Bodega. He points to a magnified photograph of thick, pink muscle fibers of a healthy abalone. In diseased abalone, those fibers are thin and shrunken. Starved abalone can die after 3 or 4 months. In the end, tens of thousands of McCormick’s abalone perished. “It was pretty traumatic,” he recalls.

The animals that survived were shipped to four labs and aquaria throughout Southern California and to Bodega as well. With about 60 adult abalone in captivity today, the recovery team doesn’t want to put all its abalone in one basket. Cherr’s group at Bodega leads the research arm of the project. The cold Northern California waters pumped into his newly built lab keep the withering-syndrome bacteria dormant. The animals that survived were shipped to four labs and aquaria throughout Southern California and to Bodega as well. With about 60 adult abalone in captivity today, the recovery team doesn’t want to put all its abalone in one basket. Cherr’s group at Bodega leads the research arm of the project. The cold Northern California waters pumped into his newly built lab keep the withering-syndrome bacteria dormant.

But if abalone are going to repopulate the sea, it must happen soon. Wild animals are nearing the end of their life spans, isolated on rocky reefs. Laura Rogers-Bennett of the CDFW collected the first group of wild abalone in 2000. “We were all pretty shocked that we could put together a seven-day cruise with a whole dive team and come home with [just] 18 animals,” she says.

Today, only one of these original abalone is alive. The ones that wait in labs are their children or grandchildren; all are at least a decade old. Researchers hope to get permission to collect more animals from the wild and breed them before the snail’s time runs out.

The spawn is on

In spring 2012, when that male abalone let loose a small puff of sperm, Aquilino almost missed it. The team had waited all day for a male to part with his gametes. Eighteen animals lingered in plastic tubs in a UC Santa Barbara lab, but only two females released eggs. Yet with no sperm, it was a wasted effort. Ironically, males — a sex known for its excess of gametes — have the most trouble in captivity.

A volunteer recognized the tiny billow of sperm. Aquilino rushed over, dipped in her pipette, and extracted all of the cloud she could see: less than one-tenth of an ounce. “It was fortuitous that we got sperm at all,” she recalls, her brown eyes gleaming behind thin-framed glasses. “It’s on the verge of a miracle that we have any juveniles.”

|

Postdoctoral researcher Kristin Aquilino at Bodega Marine Laboratory, north of San Francisco. Photo: Ryder Diaz |

|

|

Aquilino grew up in land-locked Iowa. Fascinated by water, she tromped down to the pond by her house every day to search for frogs. After a stint in Wisconsin for college, she finally got her hands in the ocean in graduate school working at Bodega. She studied snails, mussels, limpets and algae in the harsh rocky intertidal. Aquilino joined the white abalone project after completing her Ph.D. because she wanted to stay by the ocean. Now, she feels a dogged responsibility to help these snails reproduce on their own again. She may hold the future of this animal in her hands.

Aquilino doesn’t set males and females together into one tub for a romantic afternoon, because the ratio of sperm to egg is a precise recipe. The rule of thumb, says Cherr, is that five to ten sperm should attach to each egg. With too many sperm, more than one can fertilize an egg — an unfortunate spectacle called polyspermy. In an overfertilized egg, cells grow and divide where they should not. Eventually, the Frankenstein-like embryo dies.

The small squirt of sperm in Santa Barbara created 300,000 embryos. Aquilino and two CDFW researchers packed Tupperware containers full of embryo-loaded seawater into large ice chests and stuffed them into a car. New high-tech rearing facilities were waiting up north, but it was at least a seven-hour drive. Every 30 minutes, Aquilino pulled over to check that the water was a comfortable 50 to 54 degrees. At 2 a.m., they arrived at the lab for a 24-hour wait to see whether the embryos resting on the floor of the tub would hatch.

Aquilino was ready for disappointment. The last time she tried, all the embryos died and lingered at the bottom of the tub like little shipwrecked boats. But the next night, microscopic bean-like abalone larvae propelled themselves upward through the water. They beat tiny cilia that fringed one end of their bodies like tufts of hair.

Aquilino fawns over videos of magnified swimming larvae. “I’ve got these really adorable photos,” she says. “If you look at it straight on, it’s got this ring of cilia; it looks like a sun with two little eyes in the middle.” For more than a week, the abalone stayed that way, relying on their stores of yolk. To make the switch to a crawling sea snail, the minuscule larvae must suction themselves onto plates loaded with their first solid meal: diatoms. During this transition, both in the lab and in the wild, most die.

“I was up at night sure it wasn’t going to work,” says Aquilino. She spent more than three months changing filters, checking temperatures, and monitoring the lights, twice a day, for animals that were essentially invisible. People from NOAA would call and ask how many abalone there were. She couldn’t answer. “My daily routine was to take care of these animals that I didn’t even know existed,” she recalls. Then one day, she saw a tiny shelled juvenile glued to the side of the tank. A weight lifted from her; something was alive.

|

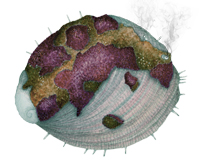

Illustration: Carolina Rivera Alvarez |

|

|

Seven months after that 2012 spawn, Aquilino plunges her hand into a tub of cold water and carefully pulls out a scrap of opaque wavy plastic. Juvenile abalone, each reddish-white and smaller than a dime, stick to the surface and quietly scrape red algae and diatoms into their mouths. “I still worry about them all the time,” says Aquilino. She carefully tucks a wisp of red algae against an abalone.

Nearby, two other identical tanks wait empty. Out of 300,000 embryos, only 24 animals survived — just 0.008 percent. The number is dishearteningly small. “If we could get 5 [percent], we’d be doing happy dances all over the lab,” says Aquilino. The truth is, she’d be happy with 1 percent.

Raising babies

In a cavernous room at the Bodega Lab, pumps hum and push cold ocean water through white pipes crisscrossing the walls and ceiling. Water rushes through a gauntlet of filters and gets zapped by UV light, killing bacteria.

If abalone arrive at the lab with withering syndrome, the animals get a bath in a tub of antibiotic for 24 hours, then get 24 hours to rest, four times in a row. One week later, Jim Moore repeats the treatment. “We want to make sure it’s gone,” he says.

There are other threats. Tiny worms and clams can drill deep into an abalone’s shell, weakening it and spreading infections. To combat parasites, the team applies nontoxic wax to the reddish shell, turning it stark white. The wax smothers unwelcome residents. Over time, it peels off naturally. “I like to compare our disease treatment methods to a Wine County spa experience,” says Aquilino. “Cleansing antibiotic baths and exfoliating shell-waxing treatments.” There are other threats. Tiny worms and clams can drill deep into an abalone’s shell, weakening it and spreading infections. To combat parasites, the team applies nontoxic wax to the reddish shell, turning it stark white. The wax smothers unwelcome residents. Over time, it peels off naturally. “I like to compare our disease treatment methods to a Wine County spa experience,” says Aquilino. “Cleansing antibiotic baths and exfoliating shell-waxing treatments.”

The therapies work; the lab’s 18 adult abalone are healthy. Now, Cherr and Aquilino want them to hand over more gametes. The team is hoping that the new facility — the first dedicated to white abalone research — will help. Wild adult abalone can be crammed full of sperm and eggs, but the scientists rarely see ripe gonads among their captives. And of the gametes that the snails do relinquish, many embryos seem to be duds, never hatching into promising larvae. Some scientists wonder if hormones and herbicides flushing out to sea might play a role. Others think it’s age. “These animals have been in captivity a long time, and they’re getting elderly,” says Cherr.

It’s a delicate task to recreate an abalone’s natural environment in a concrete room. Cherr is eager to tinker with new sets of lights, creating different lengths of “night” and “day,” and to fiddle with water temperature. With two years of matchmaking under their belts, Cherr seems prepared. “I feel like we will be able to do this,” he says. “But there’s no question there’s some luck involved.”

Despite the small number of young abalone bred last year, the team expects this year’s spawns to lead to hundreds of thousands of tiny abalone. After all, such a windfall happened a decade ago before withering syndrome struck.

Scientists have plans to deal with a surge in white abalone. Artificial reefs made of sliced-up cinder blocks — called Abalone Rearing Modules, or ARMs — now sit within several marine protected areas where the abalone once flourished. The blocks are collecting tasty algae that, scientists think, will one day be eaten by masses of baby abalone. The ARMs will shelter young animals from predators and let scientists keep tabs on them.

But for now, the team will try again to spawn 60 adult white abalone. “We’re not going to give it forever,” says Neuman, who secures funds from NOAA. “There’s only so much money and time we can put into the effort.” Until then, Aquilino will be standing by with her pipette in hand, ready to take whatever the abalone give her.

Story ©2013 by Ryder Diaz. For reproduction requests, contact the Science Communication Program office.

Top

Biographies

Ryder Diaz Ryder Diaz

B.A. (metropolitan studies, gender and sexuality studies) New York University

M.S. (population biology) University of California, Davis

Internship: KQED Radio, San Francisco (Kaiser Family Foundation health reporting program)

As a child, I spent a lot of time in the dirt. I was always hammering together scrap wood and abandoned metal springs in my backyard, or probing under twigs and leaves to examine the slimy things hiding beneath. I was a pretty filthy kid.

I went to graduate school to study ecology because my research let me stomp around in the muck and build contraptions to study bees. My hygiene improved, but my childhood drive to tinker and dig remained.

Now, I unearth scientific journeys and construct stories about them with words and with sounds. I love writing about the latest mystery, the bizarre discovery, and the science that changes lives. When I add the sounds of radio, I bring my audience right beside me, inviting them to explore our world together.

Ryder Diaz web site

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Kelly Lance Kelly Lance

B.A. (fine art) University of Nevada, Las Vegas

Certificate (natural science illustration) University of Washington

Internship: Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute

Kelly Lance is a natural science illustrator with a focus in marine life and paleontological reconstructions of the Cenozoic Era.

Kelly Lance web site

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Carolina Rivera Alvarez Carolina Rivera Alvarez

B.S. (biology) Universidad de Antioquia, Medellín-Colombia

Internships: Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum, Honolulu, HI; Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, Washington, D.C.

I have worked in Science mainly as an entomologist in museum-based projects since beginning my undergraduate studies. Although I mainly have a scientific background, I have always been interested in art and have taken art courses all of my life. However, art was so unrelated to my career that I just considered it as a hobby. When I started to be part of research projects that included working in natural history museum exhibitions, I realized that I could actually blend science and art as a scientific illustrator.

Caroline Rivera Alvarez web site

Top

|