|

Documenting Eden

Researchers race to record the biological wealth of an African island nation threatened by development, as Jane J. Lee reports. Illustrated by Sean Vidal Edgerton and Michelle Bourne.

Illustration: Sean Vidal Edgerton

Robert Drewes leans forward reverently, an eager suitor awaiting his beloved. “There she is!” he breathes. “First plant I’ve ever fallen in love with—beautiful, beautiful.” The begonia doesn’t look like much: delicate yellow petals squashed against some newsprint, its once-vibrant colors dried to muted tones. But Drewes, curator of amphibians and reptiles at the California Academy of Sciences (CAS) in San Francisco, remembers her as a young beauty, entwined with a tree trunk in a rainforest on the island of São Tomé.

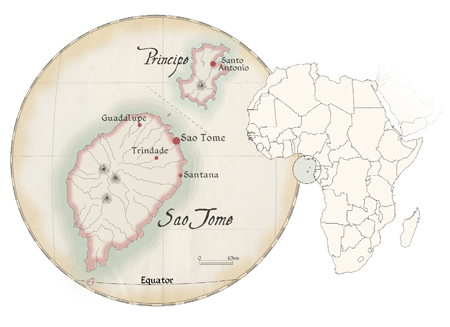

The African Republic of São Tomé and Principe, off the western coast of central Africa near Gabon, rivals the Galapagos in its concentration of birds and other species found nowhere else. At just under 1,000 square kilometers, São Tomé and Principe harbor 28 unique bird species, compared to the Galapagos’ 22 unique species in an area eight times larger.

But São Tomé and Principe’s biological cornucopia lies within spitting distance of untapped oil fields. And international companies are eyeing this country’s rainforests and beaches for hotels, ports, and other projects. Giant tree frogs, sand dollars shaped like octopuses, and three-meter-tall begonias could all vanish as this developing nation tries to clamber out of poverty.

CAS researchers are well aware of the sludge-laden waterways of oil-rich nations like Nigeria. They’ve also seen denuded rainforests and depleted soils created by poor land-management practices elsewhere. So, Drewes and his colleagues have scoured the rainforests and waded up the rivers of São Tomé and Principe, determined to record what they can before the denizens of this tiny Eden disappear.

Government officials in Africa’s second-smallest nation juggle the need to feed their people with a desire to preserve the beauty of their islands. But in a country that’s cycled through 16 governments in 20 years, a consistent plan is impossible. The CAS scientists think it’s best to be comprehensive: they’re working with all levels of government and talking to island residents, young and old, about what they stand to lose if they don’t take action.

Their slogans of protection, simple to remember, emblazon posters they plan to hand out to schools, churches, and government agencies: Only on São Tomé. Only on Principe.

The center of the world

The São Tomé and Principe islands are half of a four-island archipelago that runs northeast through the Gulf of Guinea, about 250 kilometers off the west coast of Africa. The other two volcanic islands, Annobon and Bioko, are also inhabited and belong to Equatorial Guinea.

|

Illustration: Michelle Bourne (click on image to see larger map) |

|

|

About one-third the size of Rhode Island, and with a population of about 200,000, São Tomé and Principe lie near the geographic center of the world. The island of São Tomé is about seven degrees east of the Prime Meridian, and the equator crosses the southern tip of the island. Portuguese explorers discovered São Tomé and Principe, named respectively for Saint Anthony and King John III of Portugal, in the late 1400s. They were uninhabited and ripe for colonization. Portuguese remains the national language today.

Initially a hub for sugar production and the export of African slaves, by the mid to late 1500s São Tomé was the largest producer of sugar in the world. Crops like cocoa and coffee followed in the 19th century.

Portuguese explorers in the late 1800s conducted some of the earliest studies of the ecology of São Tomé and Principe. Modern scientists have worked sporadically on these islands since then, but many plant and animal groups remain understudied or are completely unknown.

“Think of how crazy it is, now in the 21st century, to go to a couple of islands that are this poorly known,” marvels Drewes. “These utterly fell off the map. And it’s incredible that we can go over there. . . and find new stuff! Every time we go.”

Drewes has spent much of his 40-year career on the other side of the continent in eastern, central, and South Africa. But at the urging of a friend who lives and works on São Tomé, Drewes visited the little island in the late 1990s. “I sort of fell in love with the place,” he remembers. So he submitted a proposal to use the Academy’s in-house funds to lead a CAS expedition to São Tomé and Principe.

The initial Gulf of Guinea expedition in 2001 was the largest such endeavor in the Academy’s history. “It was 12 people, off and on, for 2 months,” says Drewes. “We did the whole thing for something like $10,000, if you can believe it.”

“This is the kind of thing the Academy has been doing for a long time,” says Tom Daniel, curator of botany at CAS. But he adds that past exploratory expeditions didn’t involve as many scientific disciplines or scientists as the ongoing Gulf of Guinea project. The institution’s last great comprehensive expedition went to the Galapagos in the early 1900s. “It’s really kind of rediscovering our roots in some ways,” Daniel muses.

Species explosion

The expeditions range from nearshore ecosystems to high mountain jungles. The researchers often have their hands full, literally, of rare and undescribed species. For example, Richard Mooi, curator of echinoderms (sea urchins and their relatives) at CAS, found one of the world’s most understudied sand dollars sitting in a bowl on an islander’s coffee table. “Just like hors d’oeuvres, or cookies. . . a bowl of cookies,” Mooi remembers.

When Mooi asked about them, the islander directed him to the only beach on São Tomé where dead ones wash up. Strong rip currents and waves taller than a man’s head make it hazardous to get to the colonies of animals living just offshore. Mooi and Drewes almost drowned trying to swim out to collect live specimens.

As Mooi delicately pulls a sand dollar test, or shell, out of its protective cardboard box, he grins. “It kind of looks like that guy in ‘Pirates of the Caribbean,’” he says. Two slanted, elongated holes at the top of the test give it a sinister look. Combined with the finger-like projections on the bottom half of the animal, it does resemble tentacle-faced Davy Jones.

Such rare animals and endemic species—organisms found nowhere else—are par for the course on many islands, especially old ones. São Tomé and Principe are at least 13 million and 31 million years old, respectively. Often, an island’s isolation means plant and animal immigrants don’t have to contend with the same challenges faced by their mainland relatives, such as predators, or competition for food or mates. Given enough time, this can lead to fantastic descendants of many mainland species.

|

| Slideshow: Go into the research realm at the California Academy of Sciences with photos by Jane Lee and Academy scientists and photographers. (Click image to launch show.) |

|

|

Clambering up a rickety metal ladder in the CAS collections room, Drewes pulls out an example. In the jar is a tree frog endemic to São Tomé. In life, this bright green amphibian’s brilliant orange toe-tips make it look like it hopped through the dye used to color orange traffic cones. But tucked away on a shelf with more than 22 million other specimens in an earthquake-proof room at CAS, these frogs look like huge, olive-colored jelly beans. The alcohol used to preserve specimens leaches away colors over time.

Drewes and his team found the tree frog during a collecting foray at high altitudes in the forest. “We know they’re fairly widespread above 1,000 meters in the original forest because we can hear them in the canopy,” says Drewes. But they’ve only spotted them in the water-filled holes of one giant tree. The researchers monitor that tree whenever they go back, but they keep its location secret. “Something that gaudy? Think of the pet trade,” says Drewes.

Botanist Tom Daniel has had his own share of discoveries on the islands. “The flowering plants are probably one of the better known groups there. Nevertheless, on the last trip we found a whole family that had never been recorded from islands in the Gulf of Guinea,” he says. That’s like a lion researcher heading into the savannah and discovering a completely new group of carnivores. “There are still things that come to light and blow us away,” says Daniel.

The CAS researchers have also brought back enough mosses and mushrooms to keep a small army of botanists content for years. Previously, only four mushroom species were known to science from these islands. CAS researchers recorded more than 200 species—about 60 to 80 of which may never have been seen by scientists before.

Usually, researchers describe about 25 new species of mushroom each year from around the world, explains Dennis Desjardins, a mushroom expert at San Francisco State University, in an email. “So finding 60 to 80 potentially new species from two small islands is a big deal,” he says.

This biological bonanza is not easy to come by. Researchers on the first expedition lived in a house with no air conditioning. The power cut out every day. On the equator there’s really only one kind of weather—and it’s unrelenting. The heat turns your head into a pressure cooker, warming your blood and setting up a pounding tempo. Sweating doesn’t help much, since the high humidity prevents most of it from evaporating.

The islands are also remote. “We’re doing work that can be very dangerous,” says botanist Daniel. “You’re sort of out of the reach of good medical care. If you break a leg or something up the mountain, they’ll get you down, but it’s going to be a while before you really get any attention.”

But the islanders are welcoming. Residents are generous with their time, resources, and knowledge of the flora and fauna, and the CAS researchers always hire local guides whenever they can.

The resource curse

The CAS team is the first major research group to explore São Tomé and Principe, says Hartmut Walter, a retired biogeographer from UCLA who maps where species occur.

Walter notes that most species extinctions on Earth in the past 500 years have occurred on islands. The threat is greater on smaller islands, where there’s less of a chance that some pocket of an endemic population could survive habitat destruction. “São Tomé is more important [than the Amazon] because it’s so small and unique,” he says.

“Deforestation for timber is the greatest concern,” says Gerhard Seibert, an expert on this tiny island nation at the Center for African Studies in Lisbon, Portugal. Traditional houses on São Tomé and Principe use wood in their construction. Seibert adds that erosion on beaches due to illegal extraction of sand for construction projects is another big worry. “Entire beaches have simply disappeared,” he says. “Deforestation for timber is the greatest concern,” says Gerhard Seibert, an expert on this tiny island nation at the Center for African Studies in Lisbon, Portugal. Traditional houses on São Tomé and Principe use wood in their construction. Seibert adds that erosion on beaches due to illegal extraction of sand for construction projects is another big worry. “Entire beaches have simply disappeared,” he says.

But at the same time, telling people that they can’t use their natural resources isn’t practical. “People need to work,” says Walter.

That’s why many islanders were excited when seismic studies in the late 1990s indicated there could be billions of barrels of oil just offshore. “São Tomé and Principe were compared to Kuwait,” says Paulo Cunha, former project manager of the São Tomé and Principe advisory group at the Earth Institute at Columbia University. “Oil was considered to be their way out [of poverty].”

The signing bonus the country got for an initial sale of stakes in an offshore oil field they share with Nigeria topped out at $500 million. “I think at the time, this was five times the revenue for this country,” says Seibert.

Mindful of the curse of corruption and environmental degradation in oil-rich nations like Equatorial Guinea, the São Toméan president in 2004, Fradique de Menezes, asked the Earth Institute for help. The Institute’s advisory group helped the government draft an oil revenue management law that outlined plans for spending future oil income. Mindful of the curse of corruption and environmental degradation in oil-rich nations like Equatorial Guinea, the São Toméan president in 2004, Fradique de Menezes, asked the Earth Institute for help. The Institute’s advisory group helped the government draft an oil revenue management law that outlined plans for spending future oil income.

But whether the government adheres to this law remains to be seen. The environment has been granted a reprieve of sorts: giddy predictions heralding a new oil bonanza haven’t materialized. Exploratory wells drilled by Chevron and other companies found deposits, but they weren’t large enough to make extraction commercially viable, says Seibert.

Moreover, the oil off the coast of São Tomé and Principe is in thousands of feet of water, and the equipment needed to extract it is expensive. “It’s possible that advances in technology will allow these fields to be commercially viable,” says Seibert. But those advances won’t happen tomorrow.

Only on these islands

For now, the greatest fear Robert Drewes harbors for São Tomé and Principe is habitat destruction. He feels it’s his calling to show island residents the plants and animals they share their home with. “They need at least to be aware of what they stand to lose when they have decisions to make,” he says.

Toward that goal, Drewes added an education and outreach component to the expeditions. CAS researchers send back abstracts of the papers they publish on their discoveries, translated into Portuguese. Whenever they are in-country, they make time to give talks to local communities about what they’re finding.

“On Principe, Bob [Drewes] or I can give a lecture and there are going to be people there from all walks of life, pretty much representing the whole island,” says CAS botanist Tom Daniel. “You’ll go out the next day and everyone on the island knows who you are.”

Drewes has spent years building relationships with island residents. “Places like São Tomé and Principe are a little bit distrustful of people who come and promise things. The fact that we’ve been going back, regularly, is important for both us and them,” he says.

Drewes has enlisted the help of island resident Roberta dos Santos, a former teacher at São Tomé’s only high school, on the best ways to reach her compatriots. Dos Santos works with a local community-based organization that focuses on education and training in agriculture, the environment, and health, and she appreciates what Drewes is trying to do. “He [talks] to kids in school to let them know how important are the animals we have in the islands,” writes dos Santos, whose first language is not English, in an email.

Daniel says a basic understanding of what kinds of organisms occur, where they occur, and how they function in their habitats is imperative. “Not only are we dependent on such knowledge for our food, clothing, shelter, and medicines, but as we modify the planet, knowing these things might prove to be our future salvation,” he says. Daniel says a basic understanding of what kinds of organisms occur, where they occur, and how they function in their habitats is imperative. “Not only are we dependent on such knowledge for our food, clothing, shelter, and medicines, but as we modify the planet, knowing these things might prove to be our future salvation,” he says.

As part of their outreach efforts, Drewes and Daniel, with the help of CAS education specialists Roberta Ayres and Velma Schnoll, are now reviewing proofs of colorful posters to send back to São Tomé and Principe. They feature collages of animals found only on the islands, along with names and descriptions in Portuguese. “We’re going to every school, every hotel, just passing them out,” says Drewes. “The whole point is recognition. They don’t have to know what they are, but the message is there.” Only on São Tomé. Only on Principe.

The Academy only funded the first Gulf of Guinea expedition. Since then, Drewes has had to cobble together money from various public and private sources to return to the home of his first botanical love. It may be more than a year or two between expeditions—but he is willing to wait. “I’ve got all this other stuff I’m supposed to be doing,” he says wryly, including managing the Academy's reptile and amphibian collection.

When they do return, CAS scientists will be realistic about the outcomes. “We’re in no position to be able to tell them what to do,” insists Daniel. “All we can say is ‘Wow, look what we found here. We think this is fantastic. This is only here. Cherish it.’”

Story ©2011 by Jane J. Lee. For reproduction requests, contact the Science Communication Program.

Top

Biographies

Jane J. Lee Jane J. Lee

B.A. (integrative biology and English) University of California, Berkeley

M.A. (biology, emphasis marine biology) University of California, Los Angeles

Internship: San Jose Mercury News (Kaiser Family Foundation health reporting internship)

As an undergraduate, I was shocked to learn that biology majors did things other than go to medical school. Why hadn’t I known this earlier? I spent the rest of college digging up fossils, chasing hummingbirds, and scouring tropical reefs for sea slugs. As I watched the ecological principles I learned in class play out right in front of me, I felt like I was discovering a secret world.

I loved my graduate school project on deep-sea jellies, but I realized that being an academic specialist was too limiting. Doing outreach work with inner-city students showed me that my passion lay in sparking an interest in others rather than in doing research. Science writing grounds me in a fascinating realm while letting me share my secret world with a wider audience.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Sean Vidal Edgerton Sean Vidal Edgerton

B.S. (ecology and evolutionary biology) and B.S. (plant sciences) University of California, Santa Cruz

Internships: Centre ValBio, Ranomafana National Park, Ranomafana, Madagascar; Entomology Department, Smithsonian Institution (Washington D.C.)

Main influences come from tropical biodiversity, species richness, and wildlife conservation (as well as past travels and experiences). I love to give voice to organisms that are not given the spotlight as well as educating the public on the their influence upon their environment, including those species relatively unknown.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Michelle Bourne Michelle Bourne

B.A (environmental science and policy) California State University, Long Beach

Internship: Denver Botanic Garden

I was born and raised in Long Beach, California, and practiced drawing and painting since childhood; there was never a year in school that I didn't take at least one art class. However, I decided to pursue study in the sciences after participating in a field ecology program in Grand Teton National Park during high school. It was there that I began to see the merging of art and science from the old naturalists like Olaus Murie, but it wasn't until I found the Science Illustration Program that everything just clicked. My love of art, nature, and cartography are all given expression as a scientific illustrator. As an illustrator, I hope to share the beauty and complexity of the natural world with as many people as I can. Please visit my web site to see more of my work.

Top |