|

The Salmon Snatchers

They attract tourists, harass fishermen, and devour endangered fish. Sascha Zubryd dives into the noisy world of California sea lions. Illustrated by Stephanie Rozzo.

Illustration: Stephanie Rozzo Illustration: Stephanie Rozzo

The writhing, barking mass of California sea lions on San Francisco’s Pier 39 has devoted fans. “This is incredible!” says visiting businessman Ed Cataldl of Stow, Massachusetts. He’s watching two large males battle over a corner of the most crowded dock. They smack their chests together and shove, trying to knock each other into the water. They bare their teeth and bellow at the top of their lungs. “Look at those two guys going at it,” Cataldl shouts over the din, pointing. “I’ve been here an hour and they’ve been like this the whole time.”

Tourists frequent the pier year-round to see this spectacle. In fall 2009, they gawked at a record 1,706 sleek brown bodies basking just yards from their flashing cameras. But by the end of November, the sea lions took to the waves and left San Francisco behind.

No one knew where they had gone or whether they would return. Biologists speculated that the predators traveled northward along the Oregon coast, chasing the fish and squid that are staples of their seafood diet. It's a diet that puts sea lions squarely in the middle of a thorny conservation problem.

Some California sea lions (Zalophus californianus) camp out near coastal streams where endangered salmon and steelhead gather, gobbling as many as half of the fish. They also compete with fishermen at sea. Humans and sea lions eat many of the same species, including squid, salmon, hake, herring, sardines, anchovies, and steelhead. Sea lions sometimes lurk near fertile fishing grounds, filching fish right out of fishermen’s nets and even snatching salmon off the ends of lines. There’s nothing the fishermen can do: Harassing marine mammals like sea lions is against federal law. Some California sea lions (Zalophus californianus) camp out near coastal streams where endangered salmon and steelhead gather, gobbling as many as half of the fish. They also compete with fishermen at sea. Humans and sea lions eat many of the same species, including squid, salmon, hake, herring, sardines, anchovies, and steelhead. Sea lions sometimes lurk near fertile fishing grounds, filching fish right out of fishermen’s nets and even snatching salmon off the ends of lines. There’s nothing the fishermen can do: Harassing marine mammals like sea lions is against federal law.

That law, the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972, has allowed the sea lion population to flourish. About 300,000 of them now live along western North America, from Alaska to Baja, California. The hordes chow down on endangered fish populations, and competition with fishermen can be fierce.

Scientists use satellite and GPS tags to follow the pinnipeds’ movements as they lounge in the sun, migrate along the coast, and hunt miles offshore or inland in rivers full of fish. “Understanding how sea lions interact with fisheries is important for managing the problem,” says marine biologist James Harvey of the Moss Landing Marine Laboratories, near Monterey. “They’re one of the dominant marine mammals along the coastline, and they need a fair amount of prey.”

The conflict between these hungry predators and fishermen goes back decades. It isn’t going to clear up on its own.

Peering at the pier

Most people see sea lions only on near-shore rocks or at wharves, where the blubbery masses and fishy stench draw a crowd. On a rainy afternoon in January 2011, at least 200 people braved the drizzle at Pier 39 to see dozens of the animals, which have gradually started coming back to the docks after their exodus.

“Most if not all of the animals here are male,” says volunteer Tim Vogel of the Marine Mammal Center in Sausalito. The females stay year-round with their pups at their mating grounds in the Channel Islands off the coast of southern California, Vogel explains to the tourists. Males migrate north to San Francisco and beyond to colder waters where prey is more abundant, returning to the islands in June and July to mate each year.

|

Sascha Zubryd and a guide take a look at San Francisco's popular marine loiterers. (Click on image to see video.) |

|

|

California sea lions are abundant, but that wasn’t always so. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, hunters went after sea lions’ blubber for oil, their whiskers for jewelry, and their male genitalia (known as “trimming”) for use as an aphrodisiac in Chinese medicine. Poachers raided breeding grounds and killed adults and pups for their hides, nearly wiping out the population at San Miguel Island in 1908. In the 1930s, hunters killed tens of thousands of sea lion bulls—so many that the California Department of Fish and Game expected the species to vanish forever. Until the early 1970s, fishermen who caught sea lions stealing their catches often killed their competitors on the spot.

Since 1972, the protected population has thrived. Scientists still estimate sea lion numbers the old fashioned way—by going out in boats or flying overhead and counting them. Remote tracking instruments also reveal their behaviors in more detail. Devices that look like chunky beanies with a single antenna sticking straight up are glued to a sea lion’s head or back. Simple tags beam an animal’s geographic location to orbiting satellites. Sophisticated GPS tags tell scientists not only where an animal is, but how often and how deeply it dives, and whether it’s in the water or sunning itself on dry land.

Using these tags, scientists have learned that sea lion bulls hunt within 25 kilometers of shore—sometimes for three or four days at a time—and dive as deeply as 150 meters. When warm-water events like El Niño send their prey swimming out to sea, though, the bulls travel as far as 450 to 600 kilometers out to sea. Females typically stay much closer to shore and hunt within 100 meters of the surface.

Let go of my fish!

Tracking where sea lions go and what they eat helps scientists understand when and why they compete with fishermen. Tagging an animal isn’t cheap; a simple satellite tag costs $2,000, and more versatile tags are pricier. But sea lions cost fishermen a lot more than that by damaging their equipment and snapping up their catch.

For instance, researchers at Moss Landing Marine Laboratories found that sea lions in Monterey Bay stole almost 65 percent of the salmon that fishermen had already hooked in 1997. The complete study, spanning 1997 to 1999, suggested sea lion theft and damage cost the region's commercial fishermen between $250,000 and $500,000 each year.

The impact varies from year to year, according to marine biologist Michael Weise, the study’s lead researcher. “How many animals are going after the fishing boats really depends on oceanographic conditions,” says Weise, who now works at the Office of Naval Research in Washington, D.C. A significant shift, such as El Niño, causes sea lions' prey to move to colder waters. “At those times, the animals will certainly be looking for an easy meal, and salmon boats are often their target,” says Weise. The problem is acute in Monterey. The impact varies from year to year, according to marine biologist Michael Weise, the study’s lead researcher. “How many animals are going after the fishing boats really depends on oceanographic conditions,” says Weise, who now works at the Office of Naval Research in Washington, D.C. A significant shift, such as El Niño, causes sea lions' prey to move to colder waters. “At those times, the animals will certainly be looking for an easy meal, and salmon boats are often their target,” says Weise. The problem is acute in Monterey.

In years when fishermen lose a large proportion of their catch to sea lions, they’re bound to respond. “It can be a significant portion of their income,” says Weise. “There’s a lot of emotion involved in this.” During El Niño years in Monterey Bay, Weise saw fishing boats with herds of sea lions following in their wakes before they’d even left the harbor. “The fishermen would do everything they could to shake them, but they often weren’t successful,” he recalls. “Seeing it first-hand riding in the boats with these guys—you can see the frustration.”

Despite laws protecting sea lions, fishermen sometimes take matters into their own hands. That’s when beachgoers and rescue workers find sea lions washed ashore, shot dead. In 2009, veterinarians at the Marine Mammal Center treated 19 sea lions with bullet wounds. In 2010 they treated nine, and at least five more were found shot on the Washington coast near Seattle. Although anyone convicted of shooting a marine mammal can be fined tens of thousands of dollars and even serve time in jail, convictions are rare. Most of the sea lions drift miles away from where they were shot, or they sink to the sea floor.

River monsters

Sea lion voraciousness has come to a boiling point at the Columbia River in Oregon. These once-endangered pinnipeds are now driving another species closer to extinction. The most ambitious predators travel a whopping 230 kilometers upriver to the fish ladders at Bonneville Dam, a bottleneck for Chinook salmon as they struggle upstream.

“Easy-to-catch fish all in one place—it’s a literal smorgasbord for them,” says Bryan Wright, a marine biologist with the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. “Once they learn that, they keep coming back again and again.”

The banquet affects sea lions dramatically. A typical full-grown bull tops out at 360 kilograms. But at the dam, Wright has seen animals pushing 700 kilograms.

To track their motions and behaviors, Wright and his colleagues fitted 26 California sea lions with satellite tags. The data revealed that some individuals gorge themselves on endangered salmon and steelhead, but others never swim upriver. The researchers don't know what makes a sea lion first decide to swim toward the dam; it's possible that naïve animals tag along with more experienced compatriots who have learned where the feast is. To track their motions and behaviors, Wright and his colleagues fitted 26 California sea lions with satellite tags. The data revealed that some individuals gorge themselves on endangered salmon and steelhead, but others never swim upriver. The researchers don't know what makes a sea lion first decide to swim toward the dam; it's possible that naïve animals tag along with more experienced compatriots who have learned where the feast is.

Sea lions hunt salmon and steelhead farther downstream as well. The impact is significant, Wright says: About 100 sea lions scarf up roughly 3,000 spring Chinook salmon every year. During its average lifespan of 17 years, a male sea lion might return to the river every winter. In 2010, a good year for the sea lions, they snagged about 6,000 Chinook. That’s more than 2% of all the fish. In some previous years they chomped through 4% of the Chinook, taking a big bite out of the haggard population.

When one protected species threatens another like this, conservation policy gets complicated. First, the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife tried to scare the sea lions away using underwater firecrackers and rubber buckshot fired from shotguns. Sea lions scattered at first, but their desire for easy meals won out.

Relocating troublesome sea lions doesn’t work either. In 1988 and 1989, researchers loaded 39 California sea lions into horse trailers and drove them nearly 2,000 kilometers from the Ballard Locks in Seattle to the southern California coast, near Long Beach. Within a few weeks, 29 of the animals were right back at the Ballard Locks, devouring fish. “We joked that they almost beat us back up the coast,” says James Harvey, one of the researchers involved. “We knew what would happen, but we still had to try.”

In 2006, the Oregon, Washington, and Idaho Departments of Fish and Wildlife petitioned the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) for permission to kill the most egregious offenders. The Marine Mammal Protection Act allows state governments to kill a California sea lion preying on endangered salmon, but only if the animal has consistently been seen eating the fish and can’t be chased away. In 2006, the Oregon, Washington, and Idaho Departments of Fish and Wildlife petitioned the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) for permission to kill the most egregious offenders. The Marine Mammal Protection Act allows state governments to kill a California sea lion preying on endangered salmon, but only if the animal has consistently been seen eating the fish and can’t be chased away.

NOAA approved the petition in 2008, and for the first time since 1972, a state government could deliberately kill a marine mammal legally. As of October 2010, the Washington and Oregon agencies had taken 40 sea lions from below Bonneville Dam, ten of which have new homes in zoos and aquaria. Five animals died during capture. Scientists anesthetized the other 25 and then gave them a fatal overdose of barbiturates.

[Editor's note: In November 2010, the U.S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals overturned NOAA's authorization to remove problem sea lions, directing NOAA to address "flaws" in its analysis of the sea lions' impact upon salmon populations. NOAA issued a revised authorization in May 2011, permitting the states to kill up to 85 individually identified problem sea lions each year. The authorization extends through June 2013.]

Catching the culprits

Do these radical measures actually protect fish in the Columbia River? It's hard to say. Scientists observe that even without the 40 biggest eaters, some sea lions continue to frequent their favorite coastal sushi bars in the river, including at Bonneville Dam. Whether these diners slurp up as many fish as their predecessors is unclear.

Wright and his colleagues will fit seven new GPS tags onto male sea lions during summer 2011, with more to follow. The data, Wright hopes, will reveal how much time sea lions actually spend hunting for fish while they’re swimming in the river. If the time the hunters spend foraging at the dam yields significantly more fish than they would catch spending that time at sea, it would help explain why the predators are so hard to chase away.

But to tag an animal, researchers first must catch it.

A sea lion trap is nothing fancy—it’s just a floating wooden dock surrounded by a chain link fence, with a gate sitting ready to drop shut. Sea lions often leap onto rocky outcroppings or docks to bask in the sun. “We’re at the animals’ mercy as far as when they want to haul out and if they haul out in our trap,” says Wright. “There could be hundreds of sea lions on the docks but none in the trap for a week, and then 20 of them clogging up the trap in one day.” A sea lion trap is nothing fancy—it’s just a floating wooden dock surrounded by a chain link fence, with a gate sitting ready to drop shut. Sea lions often leap onto rocky outcroppings or docks to bask in the sun. “We’re at the animals’ mercy as far as when they want to haul out and if they haul out in our trap,” says Wright. “There could be hundreds of sea lions on the docks but none in the trap for a week, and then 20 of them clogging up the trap in one day.”

When that happens, the researchers move in fast. Their small barge is equipped with cattle-chute-like compartments designed to hold the sea lions as the scientists work. The floor of the first compartment is a scale. The second has curved metal bars that adjust to fit each sea lion snugly, restraining it while the scientists tag its flippers, hot brand its backside, and measure its length and girth. They also glue a transmitter just behind the animal’s head before letting it plop back into the water. “It doesn’t seem to faze them that much,” says Wright. “The next day we see the same animals back up on the trap again.”

The work has strong support from managers of the Columbia River fisheries. “They are very concerned about how many salmon are being lost,” says Wright. “Even though it’s natural for pinnipeds to eat salmon, conflict arises in these artificial situations like the dam. It presents this very contentious, complicated, intractable problem.”

The blubbery sausages on Pier 39, alternately brawling and lazy, are far from these fatal conflicts. But the challenges of how sea lions interact with humans—and human commerce—are foremost on the minds of the scientists who’ve spent decades trying to understand these animals.

“I’d love to be able to talk to sea lions and get the straight answers,” says Harvey. “Unfortunately, it’s not that easy.”

Sidebar: Death by Algae

In recent years, rescue workers have found hundreds of sea lions with bizarre symptoms along the west coast of North America—and the number is increasing. They have seizures, swim in tight circles, and weave their heads back and forth like cobras. The culprit: a neurotoxin called domoic acid.

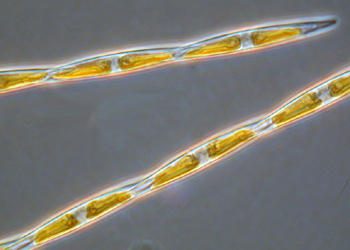

Domoic acid is produced by tiny algae sometimes found in red tides. It acts like a signaling molecule in the brain, making cells send abnormal messages. The same toxin that causes amnesic shellfish poisoning in humans is making sea lions senile.

|

Photo: Dr. Rozalind Jester/Edison State College |

Pseudo-nitschia, a marine diatom, produces the neurotoxin domoic acid under stress. |

|

|

Amnesic shellfish poisoning’s symptoms mirror those of Alzheimer’s disease: confusion, memory loss, seizures. Afflicted sea lions and other marine animals become disoriented. Without treatment, most of them die.

“It almost fries their brains,” says marine biologist James Harvey of the Moss Landing Marine Laboratories. “They do crazy things and go in all different directions.” One sea lion swam in circles for three days straight. Another got halfway to Hawaii before the signal from its satellite tag was lost.

More sick animals could mean more algae, or something could be stimulating the algae to produce more toxin—such as higher levels of nutrients from fertilizer runoff. “We don’t know exactly what turns on the production of domoic acid,” says Harvey. The increase in cases may partly be due to rescue workers and veterinarians recognizing symptoms that went undiagnosed before, he adds.

Researchers at the Marine Mammal Center in Sausalito treat sick animals with anti-seizure medication. The scientists have found that domoic acid poisoning in sea lions happens in El Niño years. But rather than building up immunity to the toxin over time, the animals get much sicker the second time they’re exposed. This could affect human seafood lovers who’ve unknowingly eaten shellfish with traces of domoic acid—if they’re exposed again, they could suffer permanent brain damage.

Story ©2011 by Sascha Zubryd. For reproduction requests, contact the Science Communication Program office.

Top

Biographies

Sascha Zubryd Sascha Zubryd

B.S. (psychology) University of California, Davis

Internship: Woods Institute for the Environment, Stanford University

I come alive when I talk about science. Whether I’m asking about marine ecology or writing about endocrine-disrupting chemicals, I light up. I’ve found myself vehemently defending evolutionary theory from inside a bathroom stall, sitting at a bar holding the interest of self-proclaimed potheads with an explanation of endogenous cannabanoid receptors, and discussing the causes of eutrophication in streams on a second date (he was a keeper, by the way).

It took an astute college mentor and the challenge of reporting about bisphenol A to point me toward science writing as a career. I had a hard time believing I could make a living doing something so interesting, so much more rewarding than listening to marketers pitch the environmental benefits of their latest drain cleaner—the one with “Toxic” on the label. What could be better?

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Stephanie Rozzo Stephanie Rozzo

B.S. (ecology and evolutionary biology) University of Arizona, Tucson

Internships: Bird Life International; UC Berkeley Sagehen Creek Field Station

As a child, I was happiest when I was drawing or playing outside with my pets. My love for animals grew into a love for science and nature, so I earned my undergraduate degree in ecology and evolutionary biology. I also took courses in drawing, color and design, and scientific illustration quench my thirst for art education. Shortly after graduating, I was employed as a zookeeper, working toward the conservation of animals through educational outreach while keeping the animals safe and healthy; however, something was missing. I was lacking time to draw and paint. When I realized that I could merge both passions as a scientific illustrator, my mind felt enlivened. I'm excited to now be working toward environmental education as an illustrator. Visit my website to view more of my work.

Top |