Walking with Pumas

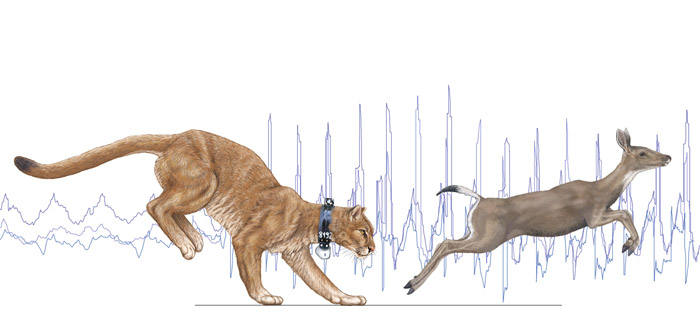

Santa Cruz biologists are tracking a consummate predator, the elusive mountain lion. Nadia Drake heads for the hills. Illustrated by Corlis Schneider.

Illustration: Corlis Schneider

It’s after dark, and I am standing six feet away from a snarling, angry mountain lion.

We’re in the mountains above Santa Cruz, in a small clearing on a gently sloping hillside. Gleaming amber eyes peer out of the darkness like two flaming spheres. Caught in a cage, the lion—a young male—is pacing like a grumpy circus tiger and pausing to hiss at visitors.

“Everybody be quiet,” says UC Santa Cruz wildlife ecologist Chris Wilmers, who asks us to regroup a short distance away and let the lion calm down. In the dark, the earthy smell of dead deer wafts from a makeshift thicket concealing the half-eaten carcass we’d stumbled upon earlier that day.

Wilmers, an energetic environmental scientist with a dry sense of humor, arrived at UCSC four years ago to study one of California’s most mysterious and misunderstood animals. His team fits pumas with high-tech collars that open a portal onto their quiet, shaded, and sporadically violent world. The gadget-packed collars constantly record each lion’s location and its activities, such as running, eating and sleeping. Data should reveal how pumas handle living in the Santa Cruz Mountains—a wilderness habitat divided by roads, dotted with houses, and surrounded by water or concrete.

“Right now, biologists are limited to knowing where animals are, but they don’t know what they’re doing,” Wilmers says. Successful conservation efforts depend on understanding the connections between an animal’s behaviors and its habitats, he adds.

So far, Wilmers and his wranglers have collared 24 lions; as of mid-2011, they were tracking 10 of them. The shy, nocturnal pumas prowl through underbrush, silently springing into trees when threatened. “They’re professionally secretive; they hide all the time. They kill by being able to sneak up on things,” says Paul Houghtaling, the team’s primary field biologist. “But people and lions work different shifts, mostly. The sun goes down and the night shift comes out.”

In pursuit of 4M

That same morning, Houghtaling is hot on the trail of puma 4M, a small male wearing a GPS-equipped collar. The collar emits radio signals easily tracked by equipment in Puma Project trucks. Riding around, we pick up 4M’s signal and pull over to establish a stronger link, hoping to download several weeks of location data off the collar. Although 4M is out of sight, he’s only several hundred meters away, moving through the redwoods near Ben Lomond.

Houghtaling stops the truck on the edge of a steep canyon. With a large, metal antenna in one hand and a small receiver in the other, he climbs to the roof of the cab, scampering around piles of equipment and sawed-off deer antlers. From the roof, he aims the antenna toward the canyon’s edge, swinging it from side to side. Soon, a faint, rhythmic chirping punctuates the receiver’s static, and Houghtaling points the antenna at the sound’s source. We still can’t see the lion, but he’s out there. Holding still, Houghtaling tries to secure the wireless link.

Photo: Nadia Drake

|

Field biologist Paul Houghtaling with radio equipment used to track tagged pumas in the Santa Cruz Mountains. (Click on image to see larger photo.) |

|

|

“Dang,” he says, looking up from the receiver after a minute. The connection had been lost. “He’s probably just over that ridge. We’ll have to move to a different spot.”

Puma 4M is a “small guy who really covers some ground,” Houghtaling says. At 117 pounds, 4M is about 20 pounds lighter than most male mountain lions in the area, but he traverses his 180-square-kilometer territory once every two weeks.

These insights about puma 4M are typical of this project, which launched in 2008 and includes collaborators from the California Department of Fish and Game. Daily fieldwork is tightly coordinated and includes tracking animals, investigating recent lion activity, and pounding the dirt roads with houndsmen and their cat-treeing dogs. Biologists keep track of kill sites, territory size, and movement in and out of the Santa Cruz Mountains. They trap and collar animals only after gaining permission from property owners.

GPS transmitters on the collars record location points every two hours. Then, researchers download and plot these points on a Google Earth map. Each point encodes the time, elevation, and temperature.

Tight clusters of points can indicate a kill site. Deer are a puma’s preferred dinner, attracting the cats to a region. (“Lots of deer grows lots of lions,” Wilmers says.) When the project's researchers notice a cluster of points, they visit the location, often looking for buried leftovers.

“We’re building a model that predicts how often and what they’re killing,” Wilmers says. “It’s kind of important for everything because lions have their influence by killing things.” Predator activity trickles down through an ecosystem and affects prey populations, smaller predators, and even vegetation—as Wilmers observed while studying wolves in Yellowstone National Park. He hopes to identify similar relationships in these mountains.

One common assumption, not yet studied in detail, is that pumas function as a “keystone” predator in the Santa Cruz Mountains, as do wolves in their ranges. Keystone predators are vital for healthy ecosystems. “They keep the prey population below carrying capacity,” Houghtaling says. “Otherwise, things like disease and starvation are going to be prey population regulators. The animals are going to suffer.” One common assumption, not yet studied in detail, is that pumas function as a “keystone” predator in the Santa Cruz Mountains, as do wolves in their ranges. Keystone predators are vital for healthy ecosystems. “They keep the prey population below carrying capacity,” Houghtaling says. “Otherwise, things like disease and starvation are going to be prey population regulators. The animals are going to suffer.”

What if the puma population could no longer fill its role? Deer populations—and the ticks they carry—might explode. That’s happened in the eastern United States, where cougars have disappeared. Decreased vegetation from increased deer munching could lead to erosion and affect the water supply. Numbers of smaller predators, such as coyotes, also could skyrocket—and unlike pumas, coyotes regularly prey upon household domestic animals like cats and dogs.

But for researchers to assess the impacts of pumas on the local forest ecosystem, they must learn more about their day-to-day lives.

Boldly going where no gadget has gone before

Those daily diaries are now being written, thanks to the project’s new tracking collars. The collars contain magnetometers, which sense the Earth’s magnetic field like little compasses and indicate which direction a lion is facing. They also house fingernail-sized accelerometers, which record speed and 3D movements, 64 times per second. Together, these two gadgets can paint a detailed picture of a puma’s behavior.

Accelerometers produce distinct data signatures for different kinds of movement. “If the animal is walking, every time the foot hits the ground it’s going to send a little jolt through the skeleton, and that’ll show itself in the data,” Wilmers says, nodding in time as he demonstrates mock lion footfalls. “If the animal is running, every time it hits the ground, it’s going to really spike. If it turns its head, we’ll know which direction it’s looking,” he says, still miming footfalls and head motions. So far, project scientists have deployed nine collars containing accelerometers, each riding on a lion’s neck for one or two years. Five animals currently sport the techno-bling accessory. Accelerometers produce distinct data signatures for different kinds of movement. “If the animal is walking, every time the foot hits the ground it’s going to send a little jolt through the skeleton, and that’ll show itself in the data,” Wilmers says, nodding in time as he demonstrates mock lion footfalls. “If the animal is running, every time it hits the ground, it’s going to really spike. If it turns its head, we’ll know which direction it’s looking,” he says, still miming footfalls and head motions. So far, project scientists have deployed nine collars containing accelerometers, each riding on a lion’s neck for one or two years. Five animals currently sport the techno-bling accessory.

Accelerometers, Wilmers explains, are the same things that make an iPhone or the Wii platform respond to a user’s motions. To demonstrate, he pulls out his iPhone and fires up an app. “This is the one my kids love,” he says, slashing the phone through the air. The screen lights up with simulated light-saber graphics and accompanying sounds as his hand parries and thrusts.

Marine-mammal researchers have used accelerometers for years—including UCSC marine biologist Terrie Williams, co-principal investigator on this project. However, Wilmers is one of the first scientists in the world to use them on terrestrial mammals. Former UCSC graduate student Matthew Rutishauser worked on developing the collar’s technology because he wanted to learn more about mountain lion activity.

“I can’t go out in the woods and stealthily stalk an animal for weeks on end,” Rutishauser says. “It’s kind of Orwellian or Star Trekkian. You’re melding this gadget and sticking it on an animal, and in the end you’re finding out some really interesting things about what the animal does.”

Rutishauser calibrated the accelerometer using dogs and treadmills. “One dog was really good on a treadmill,” Rutishauser recalls. “We had a video camera, put the accelerometer on, and filmed the animal, recording stride lengths and pace.” Pippin—a gray and black spotted dog—walked and ran on the treadmill, producing a bouncing, sinusoidal, wave-like pattern in the data. The waves varied in amplitude with Pippin’s speed, allowing scientists to identify his activities. Rutishauser calibrated the accelerometer using dogs and treadmills. “One dog was really good on a treadmill,” Rutishauser recalls. “We had a video camera, put the accelerometer on, and filmed the animal, recording stride lengths and pace.” Pippin—a gray and black spotted dog—walked and ran on the treadmill, producing a bouncing, sinusoidal, wave-like pattern in the data. The waves varied in amplitude with Pippin’s speed, allowing scientists to identify his activities.

A critical next step is getting the accelerometer and GPS to speak intelligently with one another. UCSC computer engineer Gabriel Elkaim, another project co-principal investigator, explains the need: “If the animal is chasing something, instead of wanting GPS once an hour, I might want GPS once a second because it tells me how fast he is cornering, how hard he is running, what speeds he is bursting up and down to. If the animal is asleep, we don’t need to sample at a high rate and can put everything in its lowest power mode until he moves.” A critical next step is getting the accelerometer and GPS to speak intelligently with one another. UCSC computer engineer Gabriel Elkaim, another project co-principal investigator, explains the need: “If the animal is chasing something, instead of wanting GPS once an hour, I might want GPS once a second because it tells me how fast he is cornering, how hard he is running, what speeds he is bursting up and down to. If the animal is asleep, we don’t need to sample at a high rate and can put everything in its lowest power mode until he moves.”

Elkaim plans to test prototypes using a local icon: the famed wooden Giant Dipper rollercoaster at the Santa Cruz Beach Boardwalk, which darts, dives, and whips around corners to thrilling effect. It’s a perfect place to test a GPS receiver’s ability to register fast speeds, steep hills, and rapid shifts in direction—all motions likely to arise while riding on the neck of a hungry, hunting mountain lion.

Finding felines in fragmented forests

By late morning, Houghtaling still hasn’t gotten 4M’s data. We move on, this time searching for a female, 2F, and her two male cubs. The rhythmic radio signal from her collar echoes in the truck, and Houghtaling stops to download her data.

At nearly two years old, 2F’s cubs are ready to leave their mother—but they haven’t. This intrigues the team, and it gives them another chance to collar the cubs before they set out on their own. “Males are the champion dispersers. They’re the ones who maintain gene flow,” Houghtaling explains as he studies 2F’s GPS locations. At nearly two years old, 2F’s cubs are ready to leave their mother—but they haven’t. This intrigues the team, and it gives them another chance to collar the cubs before they set out on their own. “Males are the champion dispersers. They’re the ones who maintain gene flow,” Houghtaling explains as he studies 2F’s GPS locations.

Small, geographically isolated populations—like the estimated 50 to 100 Santa Cruz mountain lions—eventually suffer from decreased genetic diversity because animals can’t easily enter or leave. Here, the mountains are ringed by the Pacific Ocean, large freeways, and developed areas.

“The long-term prognosis for a population like this is not very good, if they’re not interbreeding with other populations,” Wilmers says. The declining Florida panther is a classic case of harmful inbreeding effects, he notes: “They’ve got a population of 80 or so individuals, and they’re starting to have all these genetic defects like single testicles and infertile animals.” He keeps a sample of DNA from each captured puma and plans to analyze gene flow in the population.

The project’s data might help guide the creation of wildlife corridors that animals could use to travel safely, instead of chancing a dash across large freeways or winding mountain highways. In addition to corridors, Wilmers says a network of open spaces within populated areas could help animals move around, preserve ecological relationships, and keep populations healthy.

Back in the field, Houghtaling notices a triangular cluster of points about 100 meters from the road, recorded last night between 2 a.m. and 6 a.m. The most recent GPS reading is only several hundred meters away: 2F is still in the area, most likely with her cubs. He checks to make sure we have permission to be on this property. “Most people we run into are supportive of our research. But some people aren’t fans of it,” he explains. Back in the field, Houghtaling notices a triangular cluster of points about 100 meters from the road, recorded last night between 2 a.m. and 6 a.m. The most recent GPS reading is only several hundred meters away: 2F is still in the area, most likely with her cubs. He checks to make sure we have permission to be on this property. “Most people we run into are supportive of our research. But some people aren’t fans of it,” he explains.

Houghtaling finds we do have permission. “Let’s go see what’s going on,” he says, nimbly heading into the woods.

Overhead, two ravens are engaged in swooping courtship acrobatics as we crunch through leaves, looking for clues to last night’s activities. “We’re going to have to be pretty quiet,” Houghtaling finally says. “They’re pretty close by, and we don’t want to scare them away.”

Poking around near the cluster yields only the distinctive tracks of pumas—large, oven-mitt-sized imprints in the mud, leading farther downhill.

On our way back to the truck, we stumble across a freshly dead, half-eaten deer, its back leg broken and looped over its head, stomach ballooning like a massive gray conch shell. “See how the ribs are eaten through? That’s a good sign of lion activity,” Houghtaling says casually.

Photo: Nadia Drake

Photo: Nadia Drake |

The partially-eaten deer. Typically, pumas will cache a large animal kill and return to feed from it several times. (Click on image to see larger photo.) |

|

|

He gets on the phone, calling in reinforcements. A fresh kill means the lions will likely return this evening, especially since they’re still nearby. There are three we could capture.

Two researchers arrive with the project’s two cage traps and a snare. We haul the 2-meter-long cages down the hill, strategically planting them near the fly-ridden deer. Houghtaling anchors the snare to a tree, creates a bushy thicket from tree branches, and stashes the tempting deer carcass in the middle.

Meanwhile, we’re camouflaging the cages with more tree branches. Our bait is sawed-off legs from the fresh kill, dangling at the back of the enclosures. For lean times, the project maintains a stock of fresh-frozen roadkill. “We have many giant freezers full of deer,” Wilmers says.

Now it’s clear why Houghtaling has a box of antlers in his truck. “They take up too much space in the freezer,” he says.

Mountain lions have drawn the ire of hikers and farmers for years. Lion attacks on humans and livestock earn sensational coverage, but since 1890, only 16 attacks on people have been reported in California. Six of them were fatal. Today, pumas run into trouble when they’re caught messing with livestock—goats are a common temptation—but it’s only legal to shoot them with a valid state-issued depredation permit.

Photo: Nadia Drake

Photo: Nadia Drake |

Before attaching the tracking collar, scientists measure puma 9M's teeth, height, weight, paw size, and keep track of his vital signs during the entire sedation period. (Click on image to see larger photo.) |

|

|

For much of the first half of the 20th century, California placed a bounty on the puma. Between 1907 and 1963, hunters killed nearly 12,500 lions. In 1969, California legislators reclassified the puma as a “game mammal,” with no bounty. Then, in 1990, voters passed a ban on cougar hunting. Now the population is rebounding, standing at around 5,000 cats.

But as human populations expand further into the wild, interactions between the two are becoming more frequent. “We are looking at the nuts and bolts of how these animals are surviving and what’s changing with levels of human interaction and development,” Houghtaling says.

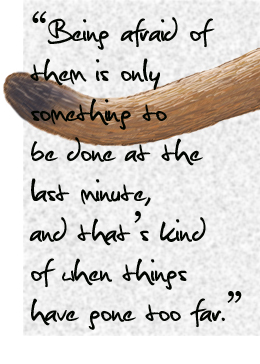

Conrad Jones, a wildlife biologist with California’s Department of Fish and Game, says the project will answer some key questions about animal movement and human-lion interactions. “I’m the guy who receives the call when people are worried,” Jones says, adding that larger numbers of people in lion territory lead to more sightings. “But the number of sightings versus the number of attacks is pretty one-sided. Being afraid of them is only something to be done at the last minute, and that’s kind of when things have gone too far.”

Occasionally, researchers need to retrieve cats who’ve died from gunshot wounds or been hit by a car. But the scientists are neutral observers, dutifully keeping track of the data. “It’s just as important to know how they die as what they do when they’re alive,” Houghtaling says.

Close encounters of the lion kind

At 8:30 p.m., I get a call saying one of the traps has snapped shut. Each is remotely monitored using a radio-tagged sensor programmed to change its rhythmic beeps if the trap goes off. One of Wilmers’s graduate students has monitored the traps since sunset, a lonely duty in the mountains.

Photo: Nadia Drake

Photo: Nadia Drake |

Graduate student Veronica Yovovich carries 9M away from the road so that he may find his bearings safely when he awakes. Team members stay with the puma until he is alert. (Click on image to see larger photo.) |

|

|

We head up, entering the dark forest punctuated by the faux sounds of dying animals coming from sound boxes placed near the traps to attract carnivores. In the distance, an amplified voice from a conservation camp run by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation adds to the auditory weirdness. “It’s creepy out here,” Wilmers observes, while waiting to move into the clearing.

One of the cage traps is full. The lion inside is indeed one of 2F’s cubs: a young male with a green ear tag, caught once before when he was a tiny kitten with big blue eyes. Now, his bottomless yellow eyes are gleaming in our headlamps as we approach the cage.

Wilmers taps on one side of the cage to distract the agitated animal while Yasaman Shakeri, a project field biologist, creeps around the other side and uses a jabstick to administer a tranquilizer. The cat, called 9M, settles down and is soon dozing. Field personnel quickly get to work taking vital signs and blood, measuring every conceivable feature, from paw width to tooth length, and constantly monitoring his temperature.

At 100 pounds, the cat is large enough to safely leave his mother. “But he’s got a lot of bulking up to do before he’s big and savvy enough to play king of the hill with a resident male,” Houghtaling says.

Then the collar goes on, and the Puma Project has another participant. In another hour, 9M will be up and stumbling around under the watchful gaze of Shakeri, who will stay with him and make sure he doesn’t wander into a road.

It’s nearly midnight before the team starts packing up, disassembling the camouflaged cages and snare set just hours earlier. The deer? That stays there.

As we leave, the stars are shining brightly overhead and somewhere in the woods, a young puma is probably happy to see his mom and brother again.

Postscript: Two weeks after this story was reported, mother lion 2F and her cub 9M separated. 9M was on his own into the spring, Houghtaling said, “in his transient phase. He’ll take a year, year-and-a-half to get some experience and bulk up.” But in June 2011, 9M was shot and killed after he attacked a goat.

Story © 2011 by Nadia Drake. For reproduction requests, contact the Science Communication Program office.

Top

Biographies

Nadia Drake Nadia Drake

A.B. (biology, psychology, dance) Cornell University

Ph.D. (genetics and development) Cornell University

Internship: Science News (Washington, D.C.)

Trees and I go way back. My first science experiment involved jumping out of one (with feathers) and trying to fly. Then, I engineered tree-forts. And now, I have returned to the redwoods of my childhood to study, live, and write.

I love the controversies, discoveries, and processes of science. But research was an imperfect career for me. My dissertation topic—the role of genomic imprinting in mouse growth and olfactory learning—was exciting, but the everyday labwork was not. I enjoyed writing primers on epigenetics for undergraduates, not designing primers for PCR reactions.

When I finally acknowledged the signs, my destination was obvious. I needed to return to what I loved: the redwoods, and writing. Now I can climb into those groves of knowledge and share them, without first having to grow them from seeds.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Corlis Schneider

B.S. (marine biology) University of California, Santa Cruz

Internship: New Zealand Marine Research Centre

There is so much beauty in science. It is a pleasure to share that through illustrations. Finding the Science Illustration Program at CSU Monterey Bay was a life-changing experience. It has allowed me to combine my passion for science and art. I am continually curious about the natural world—especially the ocean environment.

I love what I do, and I hope to inspire others about science, the natural environment, and art. Please visit my website to see examples of my work.

Top |