|

| Illustration: Rebecca Gelernter |

California condors are one of the most intensively managed endangered species. Too often, they don’t make it. Rex Sanders reports. Illustrated by Rebecca Gelernter. |

|

| |

Swooping low across a canyon inside Pinnacles National Park, California condor #444 appeared to be in fine health. “Ventana” hatched in 2007 from a nest in Big Sur, and she paired five years later with #340. The next year they fed their first chick regurgitated food scavenged from miles away. That food came from a dead animal—rotting, stinking and crawling with maggots.

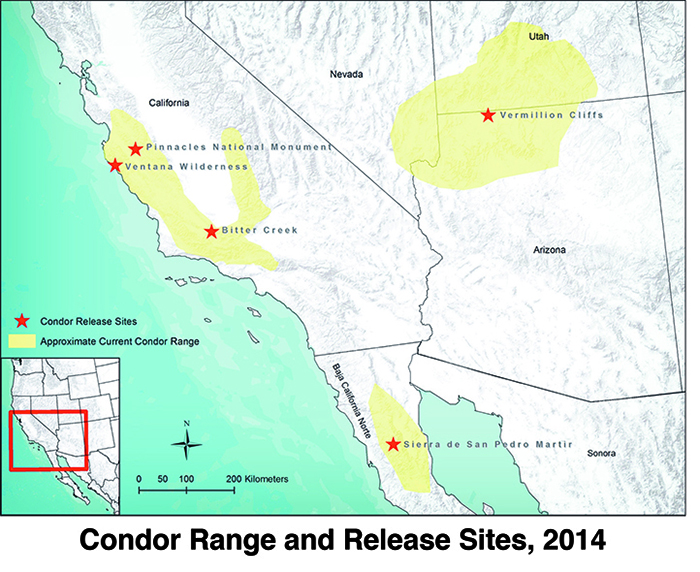

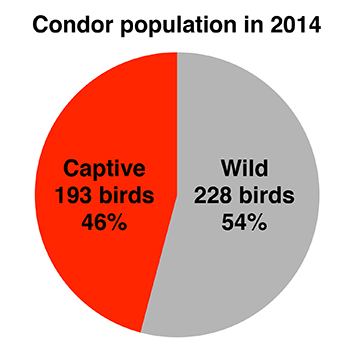

But one of the condor’s favorite meals, the gut pile left behind after a hunter kills a deer or wild pig, threatens the survival of this critically endangered species. Every year, researchers must trap about one-fifth of the free-flying condors in the western United States and Mexico to treat them for poisoning from fragments of lead ammunition in their food. Other workers lug carcasses to feeding stations and spend long hours monitoring the birds’ travels. Wild condors, now numbering about 230, would go extinct without this sustained, multi-million-dollar program of research, breeding, tracking and treatment.

Despite these efforts, lead poisoning kills about five condors each year. Many other birds spend their lives in captivity or endure awful detox treatments in zoos. Condor biologists and veterinarians will not accept that we might destroy a piece of prehistoric nature in this way. But too often, the lives they enable are difficult ones.

Melissa Clark, a field biologist for the Ventana Wildlife Society, noticed something unusual on a condor webcam late in the day on August 15, 2014. Ventana was acting lethargic and clumsy, classic symptoms of lead poisoning. Clark and colleague David Moen hustled to the feeding site near Big Sur, hoping to capture her before sunset. Instead, she roosted for the night high in a nearby tree. The next morning, they found Ventana on the ground, too weak to escape. Clark and Moen captured her and drove her to the Los Angeles Zoo for emergency treatment. This would be Ventana’s second round of lead detoxification since May.

Extensive intensive care

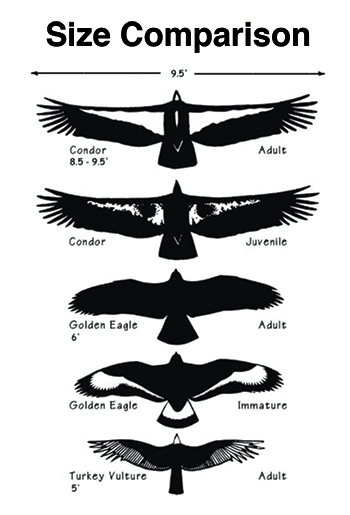

California condors are the largest land birds native to North America. With an average wingspan of 9.5 feet, they can soar for hours without flapping. They once ranged from Baja California to British Columbia, and inland to the Rocky Mountains. More than 500 of them may have flown over North America before European explorers arrived. In the late 19th century, habitat destruction, trophy hunting, and lead poisoning began to ravage the population. By 1982, only 21 condors remained in nature. After much debate over keeping condors wild versus ensuring their survival, condor managers captured them all in 1987 and began a breeding program. Crews released some of the birds starting in 1992. Nearly half remain in captivity for breeding and research, never soaring over oceans and cliffs. “Some people call it a conservation-dependent species,” says Moen.

|

Credit: Tim Huntington, Ventana Wildlife Society |

| California condor #444 “Ventana” soars over the Big Sur coast. |

Despite a diet infested with bacteria and parasites, condors can live for more than 60 years. Adults have a ruff of black feathers below a bald reddish head and neck, which helps them stay clean when feeding on the guts of carrion. They are social birds; it’s common to see up to 20 condors waiting their turn to feed on the same bloated carcass.

Ventana started life as an egg laid by a captive female in the Los Angeles Zoo. Condor crews carefully transported the egg to Big Sur. They climbed 70 feet to place it into an existing nest—a wildfire-carved hollow inside a redwood tree. Under the watchful eyes of her foster parents, she became one of the first two condor chicks to hatch in central California in more than a century. “I remember climbing into the redwood nest in 2007 and seeing her for the first time,” says Joe Burnett, condor program coordinator for the Ventana Wildlife Society. “She could fit in the palm of my hand!”

One hunter at a time

Ammunition reform is one of the most fraught aspects of the condor conservation program. Hunters can switch to non-lead bullets, typically made from copper alloys, to help the birds eat safely. However, many hunters object to the higher cost of copper ammo, how it fires and how it penetrates targets compared to lead.

Alternative ammunition isn’t even manufactured for some common guns. And a few hunters consider the condor’s management scheme a waste of taxpayer money. “I think it’s a futile effort to keep something going that by nature is not fitting into the environment we have today,” said cattle rancher Mike Shields in a recent radio interview.

|

Credit: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service |

|

A law passed in 2008 banned lead ammo in California’s condor country. But this measure didn’t reduce poisoning, despite hunter education events and copper ammo giveaways. So in 2013, California legislators passed a law banning lead ammunition for hunting statewide. It’s been a tough sell—but that’s Scott Scherbinski’s job. He’s the wildlife health outreach coordinator for Pinnacles National Park, and he’s a lifelong hunter trying to convince other hunters to switch.

Scherbinski likes to directly and honestly address difficult issues, including how much the alternative bullets cost and their availability. He also bluntly describes what happens to condors and other scavengers who eat lead fragments. At a typical event, he says, “There’s always a couple of folks standing toward the back with their arms crossed. Eventually they will come up and say, ‘I expected this to be a bunch of environmentalists trying to convince us of something that wasn’t true.’” Scherbinski thinks outreach and communication will continue making a difference in attitudes and ammunition use.

|

Video: Rex Sanders |

Ben Smith of the Institute for Wildlife Studies discusses ongoing efforts to convince hunters to use non-lead ammunition in California condor ranges. (Click on image to go to Vimeo page.) |

|

Tony Phelps switched years ago. He guides wild pig hunters in the rugged hills south of Pinnacles. “At first I was a little discouraged because [it was] an extra 20 or 25 bucks a box,” he says. “At the end of the day it’s actually a better bullet.” He makes sure his clients shoot copper bullets, too. And he’s concerned about the impact of lead bullets on other wildlife: “That’s not my goal, to have secondary animals die from a bullet that I shot.”

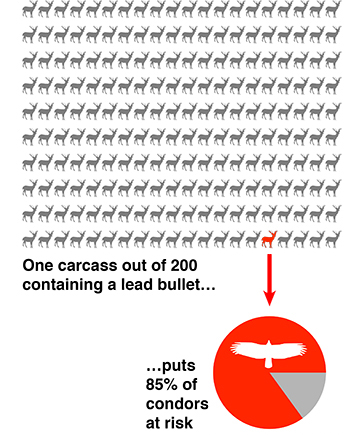

The challenge is steep: Just a handful of hunters shooting lead bullets can threaten condors. According to a recent analysis, a condor has at least an 85 percent chance of eating a lead-contaminated carcass even if only one out of 200 carcasses contain lead fragments. A sliver of lead the size of a fingernail clipping is all it takes to poison a bird.

On the condor trail

Moen drives up and down the Big Sur coast to keep tabs on free-flying condors. “We’re climbing into nests, hiking off trail up steep canyons, hauling carcasses—it all adds up,” he says. “I’m constantly going to the chiropractor in this job.”

At the Ventana Wildlife Society Discovery Center in Andrew Molera State Park, Moen fetches a well-worn pickup truck. Soon we’re zooming south on Highway 1. Moen is lean and muscular, with a close-cropped beard and a broad smile. After he warms up, the road miles disappear into long discussions about humanity’s relationship with nature. He often pauses to point out condor roosting sites, Native American shell mounds and other spots unknown to tourists. “One of the [Native American] elders told me: ‘White folks are really good at killing condors, you’re really good at bringing them back, but you are not so good at living with them,’” he recalls.

|

| Credit: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service |

We pull over at a patch of gravel lined with boulders at the cliff’s edge, several hundred feet above the Pacific Ocean. We have a view south along the Big Sur coast for about 20 miles. From the cluttered back seat of the truck, Moen extracts a handheld radio receiver. It’s connected by a 3-foot-long cable to what looks like a smaller version of an old rooftop TV antenna. Almost as soon as he points the antenna down the coast, the receiver starts beeping. “That’s oh-four,” Moen calls out as he scribbles a code onto his clipboard. “Just south of us. Probably be flying by any time.”

A pair of tourists points down the cliff to a condor. Moen leans over the edge and reads the condor’s wing tag through his binoculars. “470, see him right there with the pink head?” He records the numbers from three condors he spots below us. Condors like to hang out here, waiting for the waves to deposit sea lion carcasses on the rocks. A few years ago a much larger feast appeared. “A baby gray whale washed up down there,” Moen explains. “Every condor in the flock fed on it for four months.”

|

Photo: Rex Sanders |

David Moen of the Ventana Wildlife Society tracks California condors carrying radio tags along the Big Sur coast. |

|

Soon after a condor takes its first flight, called “fledging,” trackers like Moen climb to the nest and attach a high-visibility patch to its wing. Scientists use the unique number on each patch, like Ventana’s #444, to track the bird throughout its life. Most free-flying condors also carry a radio tracker. The louder the beep on Moen’s receiver, the closer the bird. Moen and other trackers try to find every radio-tagged condor in their assigned area every day. Some condors carry a GPS tracker instead that sends hourly positions via satellite. Ventana carried one of these.

The radio tracker transmits a special signal if the bird stops moving for a while. This signal usually means the condor is dead. If biologists can’t pick up a normal signal for several days, or if the GPS dot freezes, condor managers dispatch an airplane to search for the exact spot. Moen or a colleague then bushwhacks into the backcountry to retrieve the corpse. Scientists want to know what killed it.

Doses of poison

Ventana quickly learned where to find easy meals. At secret ridgetop sites around California, condor managers place dead cows inside fenced pens every three days. These unleaded meals help the birds survive. But condors eat plenty of other carcasses—with no way to tell if they carry lead fragments.

|

Credit: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service |

Webcams at the feeding sites can tip off biologists to unusual behavior, like Ventana’s episode in August 2014. Before that, scientists had trapped her more than 15 times in seven years. Each time the crews drew a small sample of her blood, then placed one drop into a portable lead analyzer. If Ventana’s blood lead level was below 35 nanograms per deciliter, they set her free. A human carrying that much lead risks high blood pressure, kidney failure, and spontaneous abortion.

All condor blood samples are frozen and shipped to UC Santa Cruz toxicologist Myra Finkelstein. She measures the quantity of lead and the ratio of lead isotopes in condor blood and feathers and in lead fragments. She can use the isotope ratios to rule out certain sources of lead poisoning, such as old paint on abandoned fire towers where condors sometimes roost. Lead levels in a condor’s blood represent a snapshot of recent lead poisoning, while their feathers preserve traces of lead exposure over the past few months—just as human hairs record metals in our diets.

Podcast produced by Rex Sanders. Click on image to play.

From live birds, field crews snip an inch or two off the trailing edge of a long wing feather and send the trimmings to Finkelstein. She slices those into 3/4-inch-long samples representing four to five days of feather growth. Then, in a specially protected clean lab, Finkelstein digests the feather using nitric acid and a hot plate. Ultimately, the sample becomes about 1/2 teaspoon of rusty-orange liquid in a small vial.

Each condor sampling creates 20 to 30 vials derived from two feathers, plus several vials of blood. Finkelstein carefully walks each tray of vials a few minutes across campus to a lab housing an inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer. This device, frequently found in trace metal analysis labs, vaporizes each sample using a 17,000°F stream of ionized argon gas. Then the mass spectrometer separates the elements by weight and counts the atoms. The hulking machine can measure metals like lead to one part in a quadrillion. That’s like detecting a single drop of oil in a cube of water 1,200 feet on each side.

One batch of samples takes Finkelstein about eight full work days. All that effort leads to two or three numbers. For blood and feathers, she calculates a lead concentration. For blood, feathers and lead fragments, she computes two ratios of lead isotopes. Too often, she says, her analyses rule out all plausible sources of lead—except for bullets.

Condor ICU

In human children, any amount of lead in their blood can cause developmental delays, learning difficulties, weight loss, and physical pain. Scientists cannot measure the IQ of condors, and their pain isn’t always obvious. But once a field team captures a condor for lead poisoning, the problems become clear.

For example, condors can spend up to a year in captivity during treatment. “We’ve had birds in the zoos for so long that their mates think they are dead,” says David Moen. “They move on and re-mate with somebody else. And then you release that one, and then what? You’ve just created a funky situation.”

At the Los Angeles Zoo, Mike Clark has been a condor keeper since 1989. On one video, he speaks with a calm, clear voice while he strokes a king vulture like a family pet—and the vulture nuzzles him back. Condors arrive for their lead poisoning treatment in a large dog kennel. Clark removes the bird and wraps it in an “aba,” a cloth jacket that keeps it calm. Every bird is X-rayed to expose any metal fragments or injuries. Most birds arrive with elevated lead levels but no metal fragments. These birds receive multiple rounds of chelation therapy, a chemical treatment that scours lead from their bloodstream. Each round requires five painful injections daily for five days, plus shots for antibiotics and other drugs. Once their blood-lead levels fall below 35 micrograms per deciliter, the birds are placed into large pens to regain weight and fitness before returning to the wild.

|

Source: Finkelstein et al. 2012, PNAS |

Some cases are much more challenging. A lead fragment caught in the bird’s digestive tract can paralyze and inflame muscles in that area. The condor will continue eating, but if food doesn’t move through its system, it will slowly starve. For some birds, condor keepers use their hands to push food from the bird’s crop—a food storage pouch in their neck—into their stomach. A few condors must be anesthetized so handlers can remove lead fragments and rotting food using forceps or surgery.

“We’re damned if we do, damned if we don’t,” says Clark. “If we don’t do surgery now, we’re going to lose it to lead. If we do surgery, will it survive?”

Some condors, like Ventana, are so far gone that they can barely move. A kind of condor intensive care unit houses these birds. In Ventana’s case, veterinarians twice transfused blood from captive condors into her body. Most birds getting blood “tend to brighten up, they get bright-eyed and they want to eat more,” says Clark. But the last-ditch transfusions didn’t help Ventana. “It’s just dying right in front of you, and there’s nothing you can do about it,” says Clark.

Ventana died on August 26, 2014, ten days after arriving at the Los Angeles Zoo. She was seven years old.

“To lose her so quickly and abruptly to lead was very disheartening,” says Joe Burnett, who had climbed to see her as a chick. “To see her struggling to hang on in those final days was something I never want to witness again.”

Top

Biographies

Rex Sanders

B.S. (systems ecology) University of California, Riverside

Internship: U.S. National Park Service, Point Reyes National Seashore

For more than 35 years, I’ve happily worked alongside research scientists at the U.S. Geological Survey in a supporting role. I created and ran a few unofficial outreach projects, including the popular Q&A service “Ask A Geologist.” Outside of work, I loved explaining everything from the Big Bang to molecular genetics to local history. (Friends called me “Rexipedia.”)

At my wife’s suggestion, I started writing articles for an online backpacking magazine. I mentioned those pieces to my boss during a routine weekly meeting. A few minutes later she asked, “How would you like to move into science communications?” One unlikely event led to another, and here I am, learning a new trade. Soon I hope to lead much larger audiences on grand walks through scientific fields.

Rex Sanders’s website

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Rebecca Gelernter Rebecca Gelernter

B.A. (behavioral biology) Boston University

Internship: Queen Mary University, London

Rebecca Gelernter is a science illustrator and graphic designer from New Haven, CT. She has worked and volunteered extensively in natural history museums. Rebecca’s artistic interests are primarily birds and dinosaurs. Later this year she will be interning at Queen Mary University of London, working with a paleontologist on restorations of extinct animals.

Rebecca Gelernter’s website

Top |