|

| Illustration: Reid Psaltis |

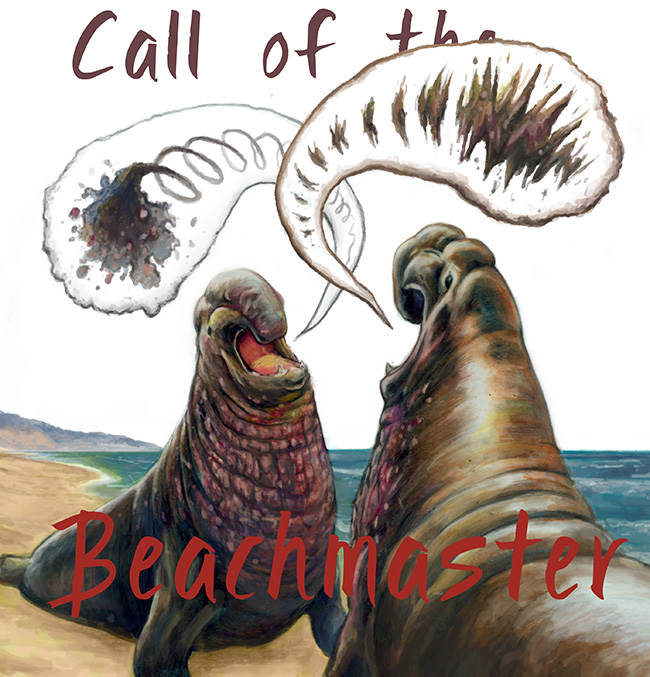

Elephant seals recognize enemies by their thunderous threats. Nala Rogers tunes in to these signature calls. Illustrated by Reid Psaltis and Georgina Podany.

A young male elephant seal known as U145 is about to make his move. He has spent the morning watching a dozen female seals lounging on a strip of beach at California’s Año Nuevo State Park. Now a sleek female on the edge of the group is weaning her pup and returning to sea, leaving the spot where she has lain for the past month. Her pup opens huge, liquid-dark eyes and calls after her, a shrill banshee cry.

The dominant alpha male heaves his battle-scarred bulk after the departing female. She is one-third the size of most males, and if she were alone, the subordinate males by the waterline would try to force her to mate. But while the alpha male escorts her and claims one last tryst in the surf, he leaves his harem unguarded.

U145 flops eagerly toward the females, but an older like-minded male cuts off his path. U145 rears up, throws his head back, and voices a challenge. His clattering call surges over the din of mothers and babies like a cavalry charge.

From her perch on a dune, an athletic young woman in rubber boots holds out a 3-foot-long microphone covered in fake fur. Caroline Casey, a graduate student in Colleen Reichmuth’s lab at UC Santa Cruz, records U145’s clap-threat call. It’s as loud as a jackhammer. The other male wheels, calls back, and lunges. The seals slam together, slashing with their long canines. Blubbery bodies shake from the impact.

U145 is a 5- or 6-year-old subadult, no match for the adult male. He recoils from the onslaught and lurches away, bleeding from his mouth and chest.

Casey lowers the microphone and looks down at the winner. She had marked him with hair dye moments before the fight; “23J” still glistens on his massive back. Why did U145 challenge the stronger male?

“I bet he didn’t know exactly who it was until 23J vocalized,” Casey says.

Casey has spent years decoding calls like 23J’s. She can identify many males by their clap-threat calls alone, and she has discovered that male seals recognize each other by voice, too. But while clap-threat calls serve as personal signatures, they are also threats—aggressive roars unlike the friendly signatures many species use to recognize kin. Now Casey and Reichmuth are studying how the calls change, both across populations and through the arc of a single seal’s life.

Roaring back

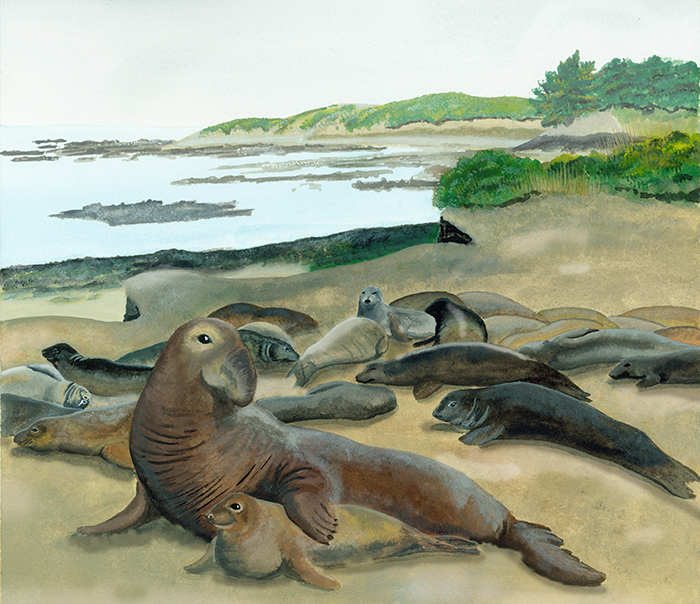

Northern elephant seals were easy prey for 19th century hunters. They are expert swimmers, diving deeper for their meals than almost any other mammal, but they are clumsy on land. Each winter they haul out on beaches to form dense breeding colonies. They don’t eat or drink during their months on the beach, so they rest to conserve energy. When they have to move, they lurch through the sand like bloated caterpillars.

Elephant seals aren’t afraid of humans. Hunters used to slaughter them by the thousands, rendering their blubber for oil. By the 1870s, people thought the species was extinct. But a tiny remnant survived on Isla de Guadalupe, a rocky outcrop 150 miles west of Baja California. The Mexican government began protecting them in 1922, and since then their population has rebounded. By 2010, more than 200,000 elephant seals lived along the Mexico and California coasts. Today, several thousand of them haul out each year at Año Nuevo—and their displays are wildly popular with tourists.

Graphic: Nala Rogers

As the seals established new colonies during the 20th century, they developed distinct local dialects. Clap-threat calls consist of rhythmic bursts of sound, and the rhythm was faster in the older southern colonies than at Año Nuevo, 60 miles south of San Francisco. Burney Le Boeuf, a pioneer of elephant seal research, first described these dialects in 1969.

“At some of these places, there were embellishments to the fundamental vocalization,” says Le Boeuf. He is recovering from pneumonia, and his declaration is punctuated by a fierce bout of coughing. “For example, at San Nicolas, the male might go 'Brrrrrrrrrrat-tat-tat-tat-tat-tat-tat-tat-Brrrrrrrrrrrrrrr.'”

These days, Le Boeuf is a bald, grizzle-faced guru whom Casey calls “the grandfather of elephant seals.” His hundreds of publications cover half a century of research, mostly at UC Santa Cruz. His wiry arms gesture with authority as he expounds on his life’s work.

Le Boeuf heard the slow, simple dialect of Año Nuevo's seals grow faster and more complex as the colony grew. The calls of adult males never changed, but the colony’s average call shifted as young seal immigrants brought their southern accents.

As the elephant seals multiplied, their dialects continued to blur. Casey is analyzing these changes. She has recorded calls from all the beaches Le Boeuf studied, plus several new ones that the animals colonized more recently. At Año Nuevo, the calls became more diverse and complex. Casey has not yet analyzed her recordings from other colonies, but to her trained ear, it sounds like the dialects Le Boeuf described have largely disappeared.

Researchers believe all of today’s northern elephant seals are descended from fewer than 100 survivors. The modern seals are so inbred that genetic testing cannot reveal a pup’s father. These shared genes mean that when two seals behave differently, their behaviors were probably shaped by learning and other environmental factors. Individual seals vary dramatically in their approaches to calling, fighting, and even mating.

“It’s kind of like the country bumpkin who falls all over the female trying to mate with her, as opposed to the Italian lover who is a little bit more subtle in his approach,” says Le Boeuf. “I mean, you have these personalities, but you don’t have the genetic differences, and that’s amazing.”

Where everybody knows your name

As soon as the departing female slips into the water, the alpha shuffles his 5,000-pound body back to his harem. He roars at the intruders crawling among his females. His thick fleshy nose dangles, vibrating with the force of his voice.

|

Illustration: Georgina Podany |

The females ignore him. Once, people thought females might select mates based on the males’ clap-threat calls. But after years of study, researchers concluded that female elephant seals don’t choose their mates at all. Instead, they choose patches of beach on which to give birth and nurse their pups. Males compete for access to groups of females: harems that range in size from a few seals to more than 100. When females enter estrus a few days before weaning, the alpha male usually gets to sire next year’s pups.

At the sound of the alpha’s roar, the invaders flop away hastily. Such peaceful outcomes are typical of elephant seal confrontations. Fights are dangerous, and they cost precious energy. Sometimes males exchange calls and threat displays, but even when both males call, one usually backs down before starting a fight. This led some researchers to suspect that the calls contain clues about each seal’s fighting ability, warning competitors away from battles they are sure to lose.

But Casey and Reichmuth’s recent research, accepted for publication in Royal Society Open Science, suggests that elephant seals don’t use clap-threat calls to size up unfamiliar rivals. Instead, says Casey, “It’s more or less a name they learn to recognize. So if Bob vocalizes and you’ve fought with Bob previously and he’s kicked your butt, then you’re going to remember, ‘Oh man, I can’t mess with Bob again.’”

To figure out what the clap-threat calls mean, Casey recorded 15 adult males multiple times. She broke down the recordings into ten acoustic measures of timing patterns and sound frequencies, which we hear as rhythm and pitch. Three of Casey’s ten measures were indeed linked to body size. However, neither the calls nor the seals’ body size showed any relationship to their rank among peers. The team observed this vocal unpredictability on the beach.

|

Photo: Colleen Reichmuth / UCSC |

| UC Santa Cruz graduate student Caroline Casey records the clap-threat call of a male elephant seal at Año Nuevo State Reserve. |

|

“When you have an alpha with a very distinctive call, you can ask yourself, ‘Who sounds most like him?’” says Reichmuth. “It’s usually not the other high-ranking male. It may be somebody on the other side of the sand dune who’s all alone.”

Each seal gave the same call in the same way, regardless of the situation, year after year. Two acoustic measures really stood out: the average pitch and the pulse rate. Pulse rate, says Casey, is the speed you would choose if someone told you to tap your foot in time to an elephant seal’s call. It is the same measure Le Boeuf used to define elephant seal dialects 46 years ago. Using just the pulse rate and the average pitch, a computer program could match a call to the correct seal about 60 percent of the time. If the calls had been random, the program would have picked the right seal only 7 percent of the time.

The acoustic analysis confirmed that each male had a unique call. But to find out what this distinctiveness meant, Casey and Reichmuth had to ask the seals themselves. They went back to Año Nuevo, found seals who were minding their own business, and played calls from a rival. When a seal heard a male who outranked him, he would usually flee. If he heard a subordinate, he behaved aggressively, calling or moving toward the speaker.

Next, they played the same recordings at San Simeon State Park, a colony 160 miles south of Año Nuevo. But while the Año Nuevo seals knew the concussive voices, the San Simeon seals heard recordings of strangers. The results were stark: “They did nothing. They sat there. We tested 20 animals, and just three out of the 20 had any response,” says Casey. “Those signals are only relevant if you have previous experience with that individual."

Calling all animals

Male elephant seals aren’t the only animals to recognize group members by their calls. Many mother animals recognize their babies by voice. This skill is well-honed in species that leave their young alone in crowded colonies, such as many bats and seabirds.

Podcast produced by Nala Rogers. Click on image to play.

“When a parent goes off to forage and brings back food for the chicks, it often needs to find a chick among hundreds of thousands of chicks in the colony,” says Peter Tyack, scientist emeritus at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. “They’ll use vocal cues to recognize one another.”

Tyack is a world expert on dolphin signature whistles, one of the best-known examples of signature calls. Signature whistles have distinct melodies, says Tyack. Dolphins develop their signatures as babies, and they use them throughout their lives to stay in contact with friends and family.

Most species use signatures as a welcome, inviting others to come closer, but the signature clap-threat calls of elephant seals are aggressive. Moreover, most threat calls in other animals are like dog barks: simple calls voiced by both sexes, and escalating with the level of threat, says Michael Noad, who studies whale songs at the University of Queensland, Australia. In contrast, elephant seal clap-threat calls come only from males—and they don’t get louder or faster to match the situation.

In some ways, a clap-threat call is like the song of a bird or a humpback whale. (“I would call it a song, except that it doesn’t sound beautiful,” Casey confesses.) Songbirds use their songs to chase away rival males, and they often recognize the songs of males that live nearby. Some researchers believe humpback whale songs also drive away rivals. But birds and whales also sing to attract mates. Elephant seals don’t.

“There’s no real need for [elephant seal] males to have a call that the females like, because the females don’t have to like anything about the males,” says Noad. “What females need is a limited resource, which is part of a beach. The males are able to dominate that bit of beach and so build up a harem.”

In contrast, says Noad, male humpback whales must attract mates because they can’t control anything the female wants. “The female simply wants a bit of shallow water,” he says. “There’s plenty of that.”

Learning the lingo

The lifespan of a male elephant seal is about 12-14 years. Mature males rarely call except to threaten rivals, but subadults between about 4 and 6 often vocalize alone. These early efforts are erratic—and loud.

Burney Le Boeuf used to spend breeding seasons in a house on the beach, near a spot where elephant seals could swim into a narrow channel between two cliffs. “A young male will go in there and start vocalizing, because there’s an echo-chamber effect,” Le Boeuf recalls. “His vocalization sounds a lot louder than it would if he were out in the open. And you can’t help but get the idea that this male is practicing.” The din used to keep him up at night.

Casey is starting a new project to discover how seals develop their signature clap-threats. Some evidence suggests that southern elephant seals mimic the calls of older males, but no one has studied call learning in the northern species. Despite the northern elephant seals’ small gene pool, researchers can’t yet dismiss the possibility that differences in calls reflect differences in genes.

Casey hypothesizes that their calls emerge like the songs of birds. Songbirds have a critical period in early life when their brains form a “template” of what their song should sound like.

“They’re not actually singing at that time. They’re just listening. And they form these memories,” says Elizabeth Derryberry, a behavioral ecologist who studies birdsong at Tulane University. “Then they go into this phase when they’re babbling like babies. So they’re making sounds, and they’re actively comparing those sounds to their memories and then refining them.” In most songbirds, the songs eventually crystallize into adult forms.

Casey plans to record young male elephant seals and track them as they grow up, pinpointing when their vocalizations crystallize into “names.” She also hopes to study the only captive male northern elephant seal, a 2-year-old named Coolio, who was injured as a juvenile and is now being raised at the Pittsburgh Zoo & PPG Aquarium. If elephant seals imitate the calls of older males, the isolated Coolio may develop a call unlike anything Casey has heard before.

Master in the making

The morning breeze at Año Nuevo bears the ocean’s fresh scent. In warmer weather, says Casey, the smells of dead pups and urine-soaked sand would waft over the dunes, too. The surviving pups nurse, sleep, and raise wide-open mouths to emit piercing cries. Mothers rumble in reply.

It’s late in the breeding season, but Casey has spent the winter studying dialects at other colonies. She was hoping to hear familiar calls here, but the Año Nuevo community has just undergone a major turnover. Only a few of the dominant males she remembers from past seasons have returned. “They presumably just drifted to the bottom of the ocean and died somewhere,” she muses. “Or they’re, you know, on a tropical island. I like to think that they just drink Piña Coladas when they retire.”

She whoops in delight when she spots 7500, an older subadult whom she recorded in the previous two years. Those earlier calls were a jumble of inconsistent sounds, which Casey describes as “vocal vomit.” He never managed to infiltrate a harem. Instead, he spent most of his time at the edge of the colony resting or vocalizing to himself.

Casey extends her fur-covered microphone as 7500 faces off against another young male. The two subadults are sleeker than full-grown males, with more refined noses and fewer scars. They rear up, roar, and thump the ground with their chests. 7500’s call is a set of long, throbbing bursts, one of the loudest calls this season. The local alpha perks up and charges forward with a bellow. The youngsters flee.

Casey caught it all. She will need to record 7500 a few more times to determine whether his clap-threat call is a crystallized signature, the sound his foes will recognize in years to come. He is about 6, on the cusp of maturity. In two years, if he survives, he could be master of the beach.

© 2015 Nala Rogers / UC Santa Cruz Science Communication Program

Top

Biographies

Nala Rogers

B.A. (biology) University of Utah

Internships: Nature Medicine, Science

As a child, I struggled to explain why the things I found—slimy or many-legged, perhaps delicately waving their antennae—were wonderful. People recoiled before I got to the best parts. So I kept them to myself and explored alone.

Later, when I shared discoveries with biologists, they understood. Their ideas ignited my own. I joined a scientific team and measured thousands of tiny bones to learn how voles fight. Amidst this clan, I was home.

Eventually, that home wasn’t enough. I realized that our knowledge of nature is immense, but most of it stays trapped in the sanctuary of academia. Now, I am learning how to share it. I write about science so that people can enjoy the slimy and the tentacular from the safety of the printed page.

Nala Rogers's website

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Reid Psaltis Reid Psaltis

B.A. (studio art) Western Washington University

Internship: American Museum of Natural History, exhibits department, New York

Reid Psaltis is an illustrator from the Pacific Northwest. While he only started in science illustration recently, his art has always focused on zoological subjects. After studying oil painting in college and creating and publishing independent comics in the following years, he finds the field of science illustration to best suit his interests and skills. After completing his internship he looks forward to whatever illustration opportunities come his way, particularly those that involve dinosaurs.

Reid Psaltis's website

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Georgina Podany Georgina Podany

B.S. (biology) Adelphi University, Garden City, NY

Internship: Delta River Overlook archaeological dig site, Fairbanks, AK

Georgina Podany is a science illustrator born and raised in New York. She spent her summers romping through the tall evergreen forests of the Adirondack Mountains, and here she discovered a deep love for the natural world. Following her passion for science, Georgina studied biology as an undergraduate, but also developed an interest in anthropology and archaeology along the way. It was through a class taught by an archaeological illustrator that she learned how to combine her love of art with her love of science. After an internship working at a dig site in central Alaska, she intends to pursue her passion for archaeological fieldwork and illustration.

Georgina Podany's website

Top |