|

| Illustration: Terra Dawson |

Beer’s oldest tradition finds a new home in the San Francisco Bay Area, and Cynthia McKelvey visits for a few sour tastes. Illustrated by Terra Dawson.

Jay Goodwin tugs on a nail jutting from one of the hundreds of oak barrels in his warehouse. He frees the nail, and a narrow stream of golden liquid arcs into a small plastic cup. He hands me the cup, steps back and watches in silence. I press the cup around my nose and inhale. Pineapple permeates my nostrils, and the faintest sting of alcohol pricks the back of my nose. The vapors feel warm on my skin. “Smells like chardonnay,” I say. Goodwin quietly chuckles and I take a cautious sip. “Almost tastes like it, too.”

But this isn’t wine—it’s beer. This batch has aged in an old wine barrel for a year. It will be another two years before it joins the next generation of sour beers at Goodwin’s brewing company in Berkeley, The Rare Barrel.

Though sour beer is the oldest tradition of beer, dating back some 3,400 years, American breweries have only begun experimenting with the persnickety style. A lot can go wrong in the lengthy and delicate orchestration of art and science as brewers work with wild yeasts and bacteria that can transform beer from delightful to undrinkable at the slightest provocation. But when it goes right, the result is an intriguing medley of flavors that can be subtly tart, strangely musty, or satisfyingly tangy.

These alchemists keep tabs on their fermenting yeasts and bacteria, affectionately called “bugs,” to endow their beers with sour flavors and hints of the country farm. Depending on the brewer, the most memorable brews come from trial-and-error or careful planning and scrupulous execution.

There’s a market for these beers, and it’s growing; sour beer is gaining popularity in the San Francisco Bay Area. Because the beers can take up to three years to mature properly, they sell for a high price—as much as $13 for a 10-ounce pour. But the craft, not the money, drives these brewers.

Partners in brew

Making a good sour beer requires a lot of patience. Goodwin, 28, spent a year monitoring the temperature and humidity of his warehouse before he ever aged a single beer there. His office computer contains a spreadsheet of color-coded data where he tracks the pH, sugar content, temperature and age of every barrel. “All those things can really impact the flavor more than people realize,” he says.

|

Jay Goodwin (left) and Alex Wallash at The Rare Barrel in Berkeley. (Photo: Cynthia McKelvey) |

“[Goodwin] has a relatively short list of things he likes to spend his time on. But he goes as deep down that rabbit hole as possible,” says Alex Wallash, Goodwin’s business partner. Goodwin and Wallash, friends since their freshman year at UC Santa Barbara, decided to start The Rare Barrel in 2012 because they both loved sour beer but had a hard time finding it. Wallash said his friends and family thought the idea of an all-sour brewery was crazy. Thankfully, some investors were crazy enough to fund their project, Wallash says.

Wallash and Goodwin are cautiously optimistic about their new venture. Wallash is tall, long-faced and all angles. He is animated, frequently switching positions when he is speaking. Goodwin is shorter and stockier. Like many brewers, he has a full, round dark brown beard. He speaks with an even-tempered, tranquil voice that seems to hide more than it reveals. He prefers to work alone, free of distractions; even his assistant has yet to witness a brew day.

Members of The Rare Barrel's Founders Club can buy exclusive bottles and fill growlers at the tasting room. But due to limited supply, Goodwin and Wallash make most of their profit from their tasting room, open on Fridays and Saturdays in a small section of the barrel house. The 20- to 30-year-olds stand around oak barrels repurposed as tables, stout tulip glasses in hand. The room resembles a posh coffee shop. Everything is made from unvarnished wood, brushed steel, and subway tiles. Hanging tungsten light bulbs provide some dim light. Wallash manages the bar, overseeing employees and answering questions about the beers. Goodwin, on the other hand, takes Friday and Saturday nights off after a long week of brewing, barreling, blending and bottling.

“It’s an interesting concept because most places that are well known for their sour beer, like Russian River, have a regular beer selection as well. I think it’s just cool that [The Rare Barrel is] all-sour,” says 28-year-old James Lee, an Oakland-based distiller and fan of sour beer. He says that The Rare Barrel is unique because “the focus is not on the brewing so much as the blending and barrel-aging.”

The Rare Barrel's tasting room. (Photo: Cynthia McKelvey)

|

A beer’s journey

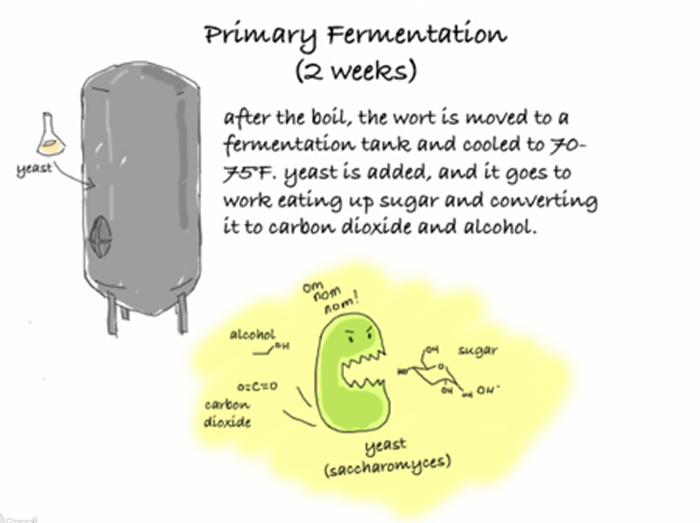

Brewing beer requires four ingredients: barley, water, hops, and yeast. The barley is steeped in water to release natural enzymes that break down starches into simple and complex sugars. Then adding hops to the mixture, known as the wort, seasons the beer. Finally a dose of yeast ferments the wort into beer. For a not-sour beer, the time between brew to bottle takes two to eight weeks.

In American ales and lagers, the brewer’s yeast of choice is generally called saccharomyces. Saccharomyces has evolved to metabolize sugars into alcohol and carbon dioxide without making too many other flavors, so brewers rely on it for a consistent product. But before the advent of sanitation and refrigeration, souring yeasts and bacteria found their way into beers and changed their flavors.

|

Interactive Graphic: A Timeline for Brewing Beer |

|

|

|

Click on the image for the full Prezi presentation. Graphic: Cynthia McKelvey |

Belgian monasteries and farmhouse breweries embraced these bugs as flavor makers. Some Trappist monasteries in Belgium have cultivated their “house” bugs for thousands of years. In the Belgian sour known as Lambic, the wort is poured into a “coolship,” a large, shallow pool exposed to the air. The wort sits overnight as strains of the wild yeast called brettanomyces descend upon the wort from the air and begin to ferment. Then the brewers transfer the wort to oak barrels, where it ferments and ages for several years.

Lambics and other Belgian sours are popular in Europe, but have only gained an audience in America in the last five years or so. Stephen Laborde, general manager at the Trappist and the Trappist Provisions bars in Oakland, says Americans—and their Budweiser palates—are new to sour beer because the craft brewing industry is still young.

Even though the Prohibition Act ended in 1933, the U.S. government did not allow states to legalize home brewing until 1979. Finally free to create and experiment, home brewers began making craft beers. Some started breweries and cultivated the American palate based on English styles of beer. English beer lends itself to bitter flavors rather than barnyard and tart flavors.

But there’s been a shift, Laborde says. Consumers are getting more adventurous and interested in trying new things. “It’s no news to anybody that kids these days latch on to whatever’s cool and hip; that’s why they’re called hipsters,” says the 44-year-old beer and wine industry veteran.

Despite the fickle hipster palate, Laborde thinks sour beer is not a fad. “What’s happening now is brewers are experimenting,” Laborde says. “They’re using the souring yeasts, they’re barrel aging, they’re doing coffee, they’re using fruit, they’re using other grains. The palette with which they paint the picture has expanded so much.”

Goodwin experiments extensively with his beers. He and Wallash have a wide margin of error in their business model. Goodwin dumps any beer that’s not right—up to 20 percent of all the beer he makes. It’s for the sake of quality control while allowing Goodwin creative freedom.

The market for sour beer is ripe. The Trappist specializes in Belgian beers and often has a few sours on their chrome taps. The modestly sized venue is cocooned in dark wood furniture. Along one of the walls is a church pew dotted with an array of customers of all ages sipping beer. They resemble birds perched on an electric line, each clad in a slouchy hat, some neck-deep in tattoos. At 4:30 on a Saturday afternoon the place is packed. The bartenders can barely keep up with the crowd.

Podcast produced by Cynthia McKelvey. Click on arrow to play.

Despite the growing taste for sour, India Pale Ales remain the beer du jour. The bitter, floral flavors still dominate as the Trappist’s top sellers. But Laborde says sours do almost as well. The consensus among brewers, bartenders, and customers is that sour beer attracts curious wine-drinkers and hardcore beer enthusiasts alike. Sours contain many similar characteristics to wine. They are about as acidic, with a pH near 3.5. Some sours are blended with fruits found in wines: raspberries, blackberries, strawberries.

“You get that bug, or that itch, where you’re looking for new interesting beer. Sour beer is where a lot of people end up finding that,” Goodwin says.

“I think that happens to a lot of people in their beer journey,” Wallash agrees. “There’s a set of people that after a certain period of time, sour beers capture their palate and it sticks.”

Laborde brings me a taste of one of his strangest sours: the Anchorage Galaxy White IPA. It’s quite unlike an ordinary IPA, with a whitish-yellow hue tinged with green. Its aroma reminds conjures my childhood, but I can’t pinpoint why. Laborde helps jog my memory: “It reminds me of when you go to a petting zoo, and there’s that….” He pauses and gazes at the ceiling. “Like, goat urine smell?” I scrunch my nose and laugh. “I was going to say rotting hay.”

Wild bugs

The intense barnyard flavor and aroma—more appealing than they sound—are from the wild yeast, brettanomyces, or “brett.” Anchorage brewed the IPA and then added brett at the bottling stage, Laborde says.

Brettanomyces doesn’t always make a beer taste funky, Goodwin says. “You can make a beer with brett that’s not sour at all, and you can make a beer with brett that’s not funky at all,” he says. “The funk flavor comes from putting brett in a stressful situation.”

|

Jay Goodwin among his barrels. (Photo: Cynthia McKelvey) |

During bottling, when saccharomyces has already fermented most of the sugar into alcohol, brettanomyces must turn to other sources of food. The yeast can eat many compounds, such as phenols, which are naturally produced by the grain, says Nick Bokulich, a Ph.D. candidate in food science at UC Davis.

“Brettanomyces is much, much slower,” than saccharomyces, says Bokulich. It bides its time, dining on a wider buffet of chemicals in the wort. Towards the end of fermentation, with little sugar remaining, brettanomyces consumes other chemicals and produces an array of byproducts that smell and taste funky, fruity, or tart. For instance, brettanomyces “chops off” a carbon dioxide from phenols, Bokulich says, to produce the smoky, sweaty smelling compounds as waste. But it’s hard to pick out any one compound that leads goat urine and rotting hay, or the pineapple flavor in Goodwin’s wort.

Bacteria play an important role in sour beer, too. Bacteria species belonging to the genus Lactobacillus consume sugar and create lactic acid. Lactic acid’s tartness is mild like peeling an orange, not sharp like biting a lemon.

“Part of our philosophy is to be as experimental as possible,” Goodwin says. Right now, he’s trying to get to know his bugs on an intimate level. He makes subtle manipulations between each batch: altering oxygen levels, brewing temperatures, and the ratios of strains of brettanomyces and lactobacillus.

Goodwin avoids putting his brettanomyces in “stressful situations,” so his beers are not very funky. They’re tart, but not overwhelmingly so. Like brettanomyces, Goodwin is taking it slow, biding his time. He says he might build a coolship, but first he needs to allow the yeast and bacteria to develop in his warehouse. As he brews more beer, the bacteria and yeast will build up in the air and become a part of the warehouse’s ecosystem.

Art vs. science

Down in Capitola, just south of Santa Cruz, a brewer with a rather different philosophy is at work. Tim Clifford serves his beers at Sante Adairius, tucked in a strip mall on a service road off Highway 1. He is more devil-may-care about his bugs, which he makes no effort to keep out of his other, not-sour beers.

|

Brewer Tim Clifford at Sante Adairius in Capitola, CA. (Photo: Cynthia McKelvey) |

Clifford runs a smaller operation than Goodwin. He brews and barrels in a brewery a little bigger than a two-car garage. One morning, Clifford invited me to watch him and his assistant Jason Hanson brew a porter. When I arrive, they are already mashing—steeping the dark, chocolatey barley in a large tub in hot water. Sweet, musty smelling steam rises from the tub as Clifford and Hanson take turns pushing the grain around with a giant metal spatula called a mash paddle.

After an hour, they transfer the brown, syrupy wort to a large kettle. Clifford dips a pitcher into the wort and pours me a small taste. It’s warm and viscous, almost the consistency of dish soap. Its sweetness overwhelms me with notes of chocolate and cinnamon. The liquid coats my tongue before sinking in, like water on dry soil.

Clifford says he once learned all the science behind brewing and then forgot it. For him, instinct and experience take him farther than chemistry. An overfull binder of notes collects dust on one of his shelves.

His tasting room is almost full by 2 p.m. on a Saturday. Cheeky signs are everywhere, like the “Der Tinkerhaus” plaque over the bathroom. All the customers are on a first-name basis with Clifford. One crowd comes down every week from Oakland just to hang out at Sante Adairius. Clifford encourages them to bring beers from all over the world to try along with his brews. His tasting room is almost full by 2 p.m. on a Saturday. Cheeky signs are everywhere, like the “Der Tinkerhaus” plaque over the bathroom. All the customers are on a first-name basis with Clifford. One crowd comes down every week from Oakland just to hang out at Sante Adairius. Clifford encourages them to bring beers from all over the world to try along with his brews.

Clifford prefers to call his sour beers “tart beers” because he feels it more accurately describes the flavors. His flagship beer, Saison Bernice, is brewed with brettanomyces. It’s hazy and golden with a medium body that finishes with a crisp tang. “I’ve found that most of my beers have been really wonderfully happy accidents,” he says.

When asked about Goodwin and The Rare Barrel, Clifford says, “They’re very scientific about it and very precise about it.” He describes their beers as “clean,” whereas his are “weird and funky and dirty.” Clifford is curious how Wallash and Goodwin will do with an all-sour brewery. It’s risky to bet on one style of beer, Clifford observes—but he says Goodwin is making a quality product.

Goodwin’s customers seem to agree. Two months after their tasting room opened, Wallash says that demand is already higher than they anticipated. Soon, they may run out of some of their beers on tap.

Quest for the Rare Barrel

Back at Goodwin’s barrel house in Berkeley, he pours me a taste of “SKUs Me.” S.K.U. (pronounced “skew”) stands for stock keeping unit, the name for the shelf space where beers are kept in stores. There often are more beers than SKUs in the Bay Area, Goodwin says. With the beer’s tongue-in-cheek name, “We’re kind of saying, ‘‘Scuse me, is there room for one more?’”

SKUs Me is made from the same golden ale recipe as the chardonnay-tasting wort from the barrel. It’s a bright golden hue with a gentle tint of orange. It tastes clean and refreshing but has just a little malt character. It’s unfunky and mildly tart. It’s an example of how a beer can be fermented and aged with brettanomyces and lactobacillus and yet be barely funky or sour at all.

|

Sour beers at The Rare Barrel take years to mature. (Photo: Cynthia McKelvey) |

Somewhere within the rows of stacked barrels is Goodwin’s optimal microbiome, The Rare Barrel’s namesake. Within a year, Wallash and Goodwin will invite select brewers, friends and beer experts to rate beers from the hundreds of barrels in their warehouse. From the top three, Goodwin and Wallash will select the one “rare barrel” as their starting culture for some beers in their next round of brewing. They will repeat the process every year, each rare barrel representing a small step toward establishing their signature style.

© 2014 Cynthia McKelvey / UC Santa Cruz Science Communication Program

Top

Biographies

Cynthia McKelvey

B.A. (biology) Oberlin College

Internship: Multiple Sclerosis Discovery Forum

I loathed science class in high school because I thought it was boring. Then David Attenborough came into my life. His documentaries, and some stellar college professors, completely changed my attitude. From chainsaw-mimicking lyrebirds to spring-loaded stingers in jellyfish, nature grabbed me and hasn’t let go.

Behind the microscope, though, I always felt like an imposter. I looked cool on the surface, making fish brains fluoresce and controlling nerve cells with electrodes. But the tedium of the protocols sapped my enthusiasm. Science lost its dazzle.

When a labmate suggested I listen to Radiolab, the concert of science, soundscapes, and storytelling captivated me. I had my “a-ha!” moment when I realized I loved the tale of the “a-ha!” moment. I wanted to thrill others with such tales. I started to write, and science dazzled again.

Cynthia McKelvey's website

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Terra Dawson Terra Dawson

B.A. (American studies) University of California, Santa Cruz

Internship: Coastal Marine Research Centre, Cork, Ireland

Terra Dawson began delving into her passion for the natural world as an undergraduate at UC Santa Cruz. The more time she spent in the redwoods, the more inspiration she drew from them. After graduating, she spent two more years working and exploring until one day she decided to revisit her old love, art. Her work has been exhibited at the Santa Cruz Museum of Natural History for the Guild of Natural Science Illustrators Art of Nature exhibit and at the Pacific Grove Museum of Natural History for the Illustrating Nature exhibit. From June through September Terra will be in Cork, Ireland as an illustrator intern for the Coastal Marine Research Centre. After that, who knows where you will find her....

Terra Dawson's website

Top |