|

| Illustration: Melissa Snider |

Hundreds of horses die at the track every year. Cat Ferguson asks whether anything can change. Illustrated by Melissa Snider and Becca Berezuk.

It is a Saturday afternoon at Santa Anita, the famed Los Angeles racetrack. Ponies jog in pairs, jockeys in bright silks bouncing on top. They line up in the starting gate, a dozen metal cages in a neat row. When the doors snap open, thousands of pounds of muscle hurtle at nearly 40 miles per hour atop ankles not much wider than a human’s. Hooves clad in feather-light aluminum slam into the dirt, shooting massive concussive force through delicate limbs, all the way to the top of the shoulder. Too often, these limbs give way under the strain, crushed or wrenched or slammed to their breaking point.

For every thousand horses that break from the gate in the U.S., two will die—that’s twenty-four a week on average. Many are euthanized on the track, shielded from the crowd’s prying eyes by a barrier, or a few hours later, when a vet determines there is no hope. Some deaths are the unpreventable consequences of sport, heaving bodies jostling in tight turns and surging limbs tangling on fast tracks. But others stem from preexisting injuries, missed by trainers or caught and then masked by powerful drugs.

Sue Stover, a veterinarian and researcher at the University of California, Davis, believes things can be better. With help from one of the country’s best research programs—every horse that dies at a state-regulated racetrack in California undergoes a necropsy—she is a leader in the fight to make racing safer for both horses and riders.

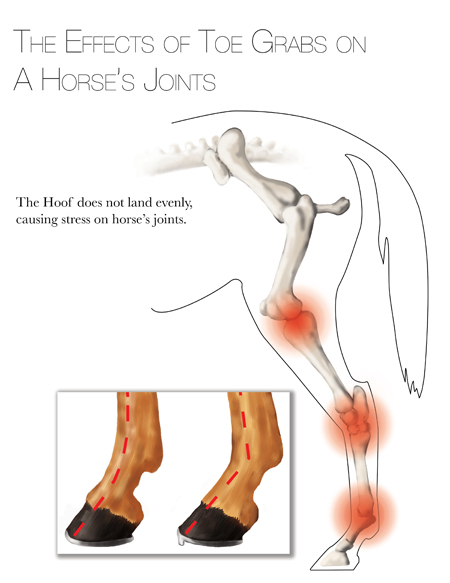

Arguably her biggest success came in 2007, when California voted to ban high toe grabs on racehorses’ shoes. Thin half-moons of steel rim the front of the shoe, biting down into the dirt. Trainers believe they give the horse extra footing on the track. Stover showed that the higher the toe grab, the higher a horse’s likelihood of dying at work.

To do so, she used epidemiological data from the necropsy program, and she tracked working horses for months to assess their injury rates. Her team also tests racetrack surfaces by hammering them with a fake hoof, runs cadaver legs through mechanical testing to assess how much pressure and pull they can take, and uses computer models to simulate how each step affects muscle and bone.

There are plenty of other data about the lives—and deaths—of these equine athletes. But is the racing industry too steeped in its own culture to respond?

A lab sized for horses

Stover meets me in a parking lot at UC Davis. She is lanky, wearing jeans and a t-shirt. Her handshake is firm, with thin fingers. Right away, she asks whether I plan to write something negative; in the past, she says, her quotes have appeared in articles that made racehorse people unhappy, and she values their support. “We prefer to prevent wrecks, rather than fix them later, whether it be journalism or horses,” she says.

She takes me into an enormous concrete room with soaring ceilings. In the middle stands a Mustang 2200, a treadmill for horses (see a video here). A short stretch of track, about three horse lengths long, rotates along under four navy blue poles that stand straight and then bend, meeting in the middle ten feet above the ground. The treadmill can go up to about 38 miles per hour, close to the speed of a thoroughbred running flat-out. She takes me into an enormous concrete room with soaring ceilings. In the middle stands a Mustang 2200, a treadmill for horses (see a video here). A short stretch of track, about three horse lengths long, rotates along under four navy blue poles that stand straight and then bend, meeting in the middle ten feet above the ground. The treadmill can go up to about 38 miles per hour, close to the speed of a thoroughbred running flat-out.

Trixie, a chestnut thoroughbred who wasn’t fast enough for the track, steps calmly onto the treadmill and begins to trot, and then canter. The clatter of hooves fills the space.

Researcher Heather Knych, who studies how drugs leave a horse’s system, tells me the horses take to the machine quickly. Trixie and her 15 herdmates are in the middle of Knych’s study on corticosteroids, the same drugs doctors inject into human joints stiff from overwork or arthritis. Knych studies inflammation and drug responses at the molecular level. The treadmill keeps the horses in shape, so their bodies eliminate drugs in a way that mimics how it happens in racehorses.

“How do we use medication for a horse's benefit and welfare, without putting them at risk for other injury or unfairly providing an advantage to those that are competing?” Stover asks. "And when shouldn't [we use drugs] because they're masking injuries,” Knych adds, glancing at Stover.

Stover and I head to her lab, featuring concrete floors with drainage grates and 15-foot-tall ceilings. Boxy contraptions sit in the middle; wide ventilation tubes swoop down to each one. Metal tracks cut across the high ceilings to move the artificial “hoof,” an upright cylindrical hammer that slams into a box filled with sand. The box, four feet deep, stands in for racing surfaces and reveals how they behave under pressure. Stover and her team take the machine to tracks around the state to measure their different properties: how they bounce back, how they compress under a foot, how far a hoof will slide.

Digging for dirt

Traditionally, horses have raced on turf—grass tracks similar to soccer fields—and dirt. Synthetic surfaces have arisen in the past few decades: mixtures of sand, clay, and polymers, coated in wax.

Largely because of Stover and other California researchers, synthetic surfaces were mandated at all major California tracks in 2006. These changes reduced fatal injuries by 37%. But the program has run into massive problems, due to both trainers complaining and issues with maintenance. Santa Anita ripped theirs out after three years, due to drainage issues; Del Mar, another Southern California track, is applying for a permit to return to dirt in 2015, which will make the track eligible to hold the prestigious Breeder’s Cup. That leaves just one synthetic track in the state, Golden Gate Fields, near San Francisco. Between 2012 and 2013, synthetic tracks had the fewest fatalities, but Santa Anita’s dirt wasn’t far behind.

Graphic: Cat Ferguson

Part of the team's work on safer surfaces involves examining bones from racehorses that die at the track. Stover leads me into a small room lined with metal shelves covered in boxes. Many are full of bones. She hands me a humerus, the lower of a dead racehorse's two shoulder bones. One end is as porous as worn sandstone.

"These are repetitive overuse injuries," Stover says. "This particular lesion is one of the main reasons that bone scanning was installed at Santa Anita. We know that well over 85% of horses that die from a bone fracture die because the bone has a weakness. The next step is, how do we detect the preexisting injury?" Stover runs a finger over the bone. "This horse, if it was allowed to heal, would have had normal performance afterwards."

Stover hopes to teach trainers and vets how to look for early warning signs, and which training regimens are closely associated with later fatalities.

A day at the races

I head to Santa Anita to see the track for myself. The daily racing program is sized to fit in a back pocket, sticking out a little for easy access. It costs $12, so I ask a woman to borrow hers. It’s the last bet of the day, and she hurries off before I can get her name.

On each page there are names and stats for the thoroughbreds racing that day. Next to almost every name, there is a bold capital L. A key at the bottom explains: these horses take Lasix, a powerful diuretic and coagulation drug. In racehorses, it’s used to stop exercise-induced pulmonary hemorrhage, when a horse’s lungs start bleeding. Horses susceptible to the condition are called “bleeders.”

Lasix is the only legal race-day medication in the U.S. It's outlawed in most other countries, though, both because it masks bleeding and because the diuretic effect can hide drugs from urine tests. But on days prior to the race, most horses will get plenty of drugs: non-steroidal anti-inflammatories, corticosteroid injections in sore joints, and various other bronchiodilators, painkillers, and even baking soda, poured through a tube into the stomach. Affectionately called a “milkshake,” the latter is supposed to neutralize lactic acid buildup in working muscles.

All of these injections, pills and tubes add up to a dangerous cocktail, one that can hide the pre-existing conditions Stover knows lead to fatal injuries. When I ask about one change she’d like to see on the racetrack, she pauses for several seconds and then clears her throat. “I’m going to put it in very soft terms, so please do that,” she says, waving at my notebook. She wishes racetrack people would “reconsider medication, so trainers and veterinarians can have an opportunity to work with the horse on a more knowledgeable basis.”

Drugs don’t just hide trouble; they can also create it. Anabolic steroids were outlawed in all racing in 2010, but a number of other medications, including clenbuterol, can mimic the effects, putting muscle mass on a horse quickly without building bone or strengthening muscles to support the bulk. In California, trainers must stop administering clenbuterol 21 days before a race. “If you put those meds into a horse, you’ll make them bigger and faster, but it’s like putting a V8 engine in a VW Rabbit. What’s going to happen? You’ll rattle the wheels off,” says Russell Cohen, a Kentucky-based vet and horse breeder.

Farrier Keith Bowen, who has been shoeing horses in California for four decades, agrees to show me around Santa Anita’s stable area. A good farrier travels from track to track as the horses they shoe move around the country to race. “A horse shoer’s not going to make them faster, he’s just going to keep them sound,” Bowen says. The wide differences in track surfaces sometimes mean changing the way a horse is shod.

“Synthetic has a way of stopping horses when the foot lands. It’s not a natural way of going,” Bowen says. He pulls a shoe out of the many boxes piled high in the back of his truck. It’s light in my hand, aluminum with rounded edges meant to slide on synthetics. “That’s the Synergy, that shoe there. They make some difference, but not a huge one, on synthetics.” It has a low toe grab, under the four-millimeter standard set in 2007 based on Stover’s research.

|

|

Illustration: Becca Berezuk |

|

Through post-mortem data and by studying horses in training, Stover showed that horses wearing toe grabs larger than four millimeters were 16 times more likely to be fatally injured on the track than those with flat shoes. The grabs tip the horse’s foot up in front and down in back, putting enormous pressure on ligaments and tissue, especially under the concussive pressure of a race.

In 2006, the California Horse Racing Board voted to limit toe grabs, then voted not to enforce it. A year later, the standard was finally adopted. Low toe grabs still double a horse’s risk of catastrophic injury, but the racing culture resists change, whether in shoes or on tracks.

Bowen puts the shoes away and takes me for a walk. Heading into one of the barns, he steers me into a side office. The walls are lined with framed photos of horses racing, jumping fences, standing in the winner’s circle. Bowen introduces me to Matt Chew, a trainer with a bluetooth earpiece and carefully chosen words that suggest media training. Chew invites me to watch a chestnut filly work out. She’s three, he tells me, but she's not yet ready to race.

Walking towards the track, he lists generations of horse trainers in his family. When I joke that he’s like racing royalty, Chew chuckles without humor. “A lot of people would laugh if they heard you say that.”

The sport of kings

When Bowen first introduced us, I couldn’t place Chew’s name. It is only as we climb the stairs to the top of the stadium that he reminds me why I’ve heard it before. He explains that he was in charge of the 50 horses who starred in the ill-fated HBO television series Luck, which was canceled after three of the show’s horses died at Santa Anita. Two suffered injuries on the track that required euthanasia. The third reared over on the backside of the track, cracking its skull open. I have trouble linking the man excoriated in the press as a horse killer with the man next to me on this chilly L.A. morning.

This keeps happening. In the paddock, where horses are saddled before a race, owners scratch their horses’ necks. Trainers talk to the press about their horses like they would about their children. These are horse people. And yet, horses continue to be drugged and to die in unacceptable numbers.

According to a poll by the Jockey Club, 80% of bettors take into account the possibility of illegal drug use when handicapping races. In November of last year, three trainers—one with more than $1.5 million in winnings in 2013 alone—were arrested and charged with defrauding bettors by illegally doping horses. “There are people in horse racing in prominent positions that have no reason to be there,” says Russell Cohen. “Being a breeder of well-bred horses, I wouldn’t allow 75% of people in this game to get involved with me.”

Chew knows well the highs and lows of racing. “The winner’s circle, that’s the best that life can give you, but on the other end, like dealing with a catastrophic injury, that takes you to a dark place.”

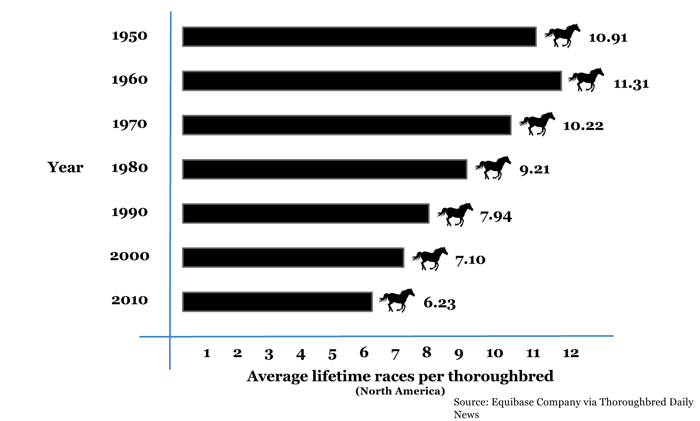

His eyes are on the track, thumbing his watch on and off for the chestnut filly galloping below us. “Everyone is so focused on percentages that trainers are deathly afraid of leading horses to the gate when they’re not going to win. Used to be, we’d throw them in a race and tell the jockey, don’t push them, just to teach them how to run. But now owners will hear, so and so’s good with first-time starters,” he says, glancing at me and then back at the track.

Most of these first-time starters are two years old, an age at which a horse’s knees are not yet fully developed. “There is conventional wisdom that racing horses at [that age] is akin to sending kindergartners to the Olympics. In reality, horses that make their first racing start later in life are at substantially increased risk of fatal injury,” says Mary Scollay, the equine medical director of the Kentucky Horse Racing Commission. “When a horse is in his two-year-old year, the bones are most adaptable to training. If you train the bones at that point they’re more able to sustain racing over time.”

It’s tough to confirm this, because so many horses start racing at two that a comparison is difficult to find. Indeed, horses who start racing later usually do so because they were injured preparing for a first race when they were two. But regardless of what epidemiological data might reveal, no one I talked to suggested starting a racing career later—especially since many major races, including all three Triple Crown starts, happen at three years old. No one wants to miss out on their chance.

Standing atop the stands, watching the horses—sleek and lean, thin tails streaming behind them—I thought of a conversation I’d had with Mick Peterson, executive director of the Racing Surfaces Testing Laboratory, a non-profit dedicated to finding the best surface possible.

“As far as I’m concerned, the injuries ruin it," Peterson said. "If you get so you’re comfortable with that, then your soul is dead. But by the same token, you watch Santa Anita first thing in the morning, and the horses are so happy. I look at the horses, and they’re doing what they want to do. We have a moral responsibility to protect them.”

© 2014 Cat Ferguson / UC Santa Cruz Science Communication Program

Editor's note: After a rash of horse deaths this summer at the Del Mar racetrack near San Diego, including four fatalities on Del Mar's new turf course, officials closed racing for eight days in August on the grass track. According to the Del Mar Times, racing resumed only after vigorous aeration and watering softened the course. Track officials also eliminated shorter turf races, called sprints, and have forbidden lower-caliber "claiming" horses from running on the grass, the Del Mar Times reported.

Top

Biographies

Cat Ferguson

B.S. (neuroscience) Northeastern University

Internship: Retraction Watch

The first time I wrote about science for real people, I read at least 15 papers on how our bodies respond to music. Each one was denser than the last. The article, just 400 words, ran in my undergraduate science magazine (circulation: 1,000). It was a fun but time-consuming hobby, separate from my destiny as a neuroscientist. I thought I could satisfy my investigative streak by pestering rats, eking out small truths with snapshots of their brains.

But every time I dug into journals or called a scientist, I grew fonder of translating Science into English. Soon I was running that magazine and pitching my first paid stories to national editors. I kept my head down and earned my degree, but I’m happy to leave the rats to the neuroscientists. I’ve got writing to do.

Cat Ferguson's website

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Melissa Snider

B.A. (studio art) University of California, Davis

Internship: New Zealand Marine Studies Centre

Melissa is an illustrator and California native who studied studio art, animal husbandry, and French before joining the Science Illustration Program. She enjoys working in gouache and watercolours; her favorite subjects include vegetables, insects, and horses.

Melissa Snider's website

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Becca Berezuk

B.A (environmental studies) College of the Atlantic, Bar Harbor, Maine

Internship: California Academy of Sciences

When I discovered scientific illustration could be pursued as a career, I knew immediately it was for me. I have always been interested in both art and science; I’ve studied botany, ornithology, ecology, natural history, photography, and fine arts. I hope to illustrate for a university, publisher, or in a research facility. I'm interested in working in natural science, botanical, and wildlife illustration. I want to use the tool of illustration to communicate research, help introduce theories, educate, and make innovation and discovery more approachable.

Becca Berezuk's website

Top |