|

| Illustration: Fiona Lee MacLean |

As drought threatens the Santa Cruz water supply, division paralyzes the city. Becky Bach clarifies the alternatives. Illustrated by Fiona Lee MacLean and Leah Hammon.

A fallen fir blocks the creek’s flow, forming a shallow pool. “There’s one!” a woman cries out, pointing at a pencil-length fish, its shiny outline barely discernible. “That steelhead’s one, maybe two years old,” says biologist Don Alley, identifying the fish that brought this small group to the banks of Fall Creek on a sunny January afternoon.

Fall Creek, a tributary of the San Lorenzo River, should be gushing. Yet this year, it barely trickles. Only two inches of rain had fallen by midwinter, less than one-tenth of the region’s norm. By June, Santa Cruz County grimly marked its second straight abnormally dry year. Headlines across California heralded a “drought emergency,” but the 60,000 residents of Santa Cruz were worse off than most.

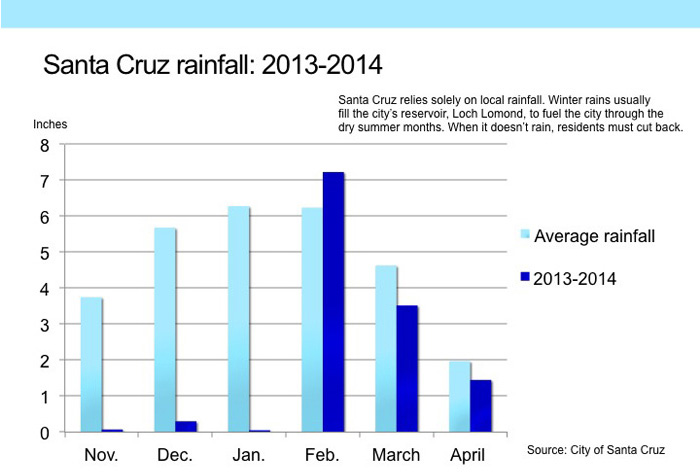

The city’s water weaknesses seem surprising. Santa Cruz perches beside the Pacific Ocean—a town of surfing and sailing where you can watch whales each winter. The San Lorenzo River—which beckoned Franciscans to its sandy banks in 1791—slices the city in two. Yet despite the water, water everywhere, for drinking there’s only the San Lorenzo, a few streams, and a sliver of an aquifer already imperiled by saltwater. Most California communities derive at least some water from the supple Sierra snowpack. Not Santa Cruz. Here the equation is simple: no rain, no water. That’s why the city dammed Newell Creek in the 1950s to form Loch Lomond, a reservoir that sustains Santa Cruz through the dry summers. It’s a scenic 175-acre water tank, but it still depends on regular rainfall. Water shortages always hover mere months away.

Despite a few droughts, Santa Cruz prospered. The lower San Lorenzo teemed with salmon and the city swelled. In 1965, the University of California opened a new campus in the redwoods above town, adding hundreds of students, then thousands. To slake the community’s growing thirst, the city purchased a private well system south of town and siphoned ever more water out of the river. Planners scoured the hills for a new reservoir site. Yet all was not as perfect as the postcards sold on Beach Street portrayed. Years of logging and road building upstream left the San Lorenzo clogged with silt, which smothers fish eggs. Salmon populations plummeted; the federal government declared both steelhead and coho salmon imperiled in the mid-1990s. Reservoir plans fizzled.

Now, to comply with federal regulations, the city must slash its supplies: the fish need more water to navigate tricky in-stream obstacles. Cutting back might work if it rains regularly. But in a drought—or in a climate skewed by rising temperatures—all bets are off. Forget fish, there won’t be enough water for people.

And as supplies shrink and fish struggle and the sun beats down on central California, Santa Cruz clashes. The community is locked in a paralytic debate that seems as immutable as the drought.

Desal delays

Well before the current drought, the city’s leaders had a plan. They’d found a new source that showed no signs of drying up. Thanks to advances in materials science, the cost of desalinating seawater was steadily dropping. San Diego and other Californian cities were eyeing the technology used in the Middle East to provide potable water, and Santa Cruz joined in. Tapping the ocean seemed the best solution.

A Santa Cruz-size plant sported a $115 million price tag just to build, much less to operate. And an energy-gobbling plant directly challenged the city’s efforts to reduce carbon emissions. Moreover, the plant would siphon water from the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary, an ecological treasure trove hosting more than 500 types of fish.

But come drought, or climate change, or fish-saving cutbacks, a plant would dependably crank out water—just power it up.

In 2005, the city partnered with its southern neighbor, the Soquel Creek Water District, and dove into preparations. Together, they conceived of a 2.5-million-gallon per day plant in a westside industrial area, close to Natural Bridges State Beach. Preliminary polls showed a slim majority of Santa Cruzans supported the idea, so the city’s leaders plugged forward.

|

Rick Longinotti of Desal Alternatives at the San Lorenzo River in Santa Cruz. Photo: Becky Bach |

|

But as planning progressed, a small group of protesters led by electrician-turned-therapist Rick Longinotti morphed into a community-wide network of opponents. The issue ignited deep-rooted passions. As a large engineering solution to outdo nature, the plant embodied everything residents of this left-of-liberal berg detest. Opposing desalination let activists combat climate change, or population growth, or most any cause of their choosing, right in their hometown.

This is a city where the radio DJ oinks on air, locals rally to “Keep Santa Cruz Weird,” and anarchists repair bikes at a “church” downtown. Sports fans cheer on the university’s fighting banana slugs and deadheads flock to its Grateful Dead Archive. Santa Cruz has yoga and bookstores and vegan cafés galore, not to mention redwood forests and wide beaches.

“Santa Cruz has always been sternly environmental and [desalination] is just anti-environmental at its core,” says Gary Patton, an environmental attorney and former county supervisor. “It’s not the way we should approach our relationship to the natural world.”

Activists plastered “Desal Sucks!” bumper stickers on their cars and crowded community meetings. Powered by an inchoate anti-growth, anti-fossil fuel, anti-corporate sentiment, 72 percent of Santa Cruz voters spoke clearly at the polls in November 2012: any desalination project must face an election to proceed.

Less than a year later, the city released a draft environmental report for a desal plant. The hefty document elicited hundreds of critical comments from local residents. State and federal regulators also assailed the city’s work, faulting everything from the adequacy of its analyses and its proposed alternatives to its math. (With dry bureaucratese, an Aug. 13, 2013, letter from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife captures the disparity: “The draft EIR states that there is a low likelihood of occurrence for the brown pelican; CDFW disagrees… there is a high likelihood of occurrence for the brown pelican.”) If Santa Cruz chose to pursue a plant, it might need to redo the multimillion-dollar report. Less than a year later, the city released a draft environmental report for a desal plant. The hefty document elicited hundreds of critical comments from local residents. State and federal regulators also assailed the city’s work, faulting everything from the adequacy of its analyses and its proposed alternatives to its math. (With dry bureaucratese, an Aug. 13, 2013, letter from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife captures the disparity: “The draft EIR states that there is a low likelihood of occurrence for the brown pelican; CDFW disagrees… there is a high likelihood of occurrence for the brown pelican.”) If Santa Cruz chose to pursue a plant, it might need to redo the multimillion-dollar report.

The city’s longtime water director, Bill Kocher, announced his retirement in early August 2013. Then on Aug. 20, the mayor and city manager issued a joint statement, making public what everyone already knew: the plant didn’t have the public or regulatory support to proceed.

When anyone talks about desalination in Santa Cruz, Kocher’s name comes up. After leading the department for nearly three decades, Kocher is vilified by desalination opponents as the driving force behind the plant. “It became mine. I was the face of it,” he acknowledges. Kocher’s position as a founding member of a statewide desalination advocacy group, CalDesal, fueled the community’s distrust.

The 65-year-old new retiree insists the desal debacle didn’t push him out. But it did mark a suitable stopping point. “Had it not been unraveling, I would have hung in there,” Kocher says. “I didn’t intend to die in that job. Somebody else can take it on from here.”

That somebody is Rosemary Menard, a local unknown who hails from Reno. Kocher now plays with grandkids and rides his Harley, but he still believes the city needs that desalination plant.

“We’re on a collision course,” he says.

Against the flow

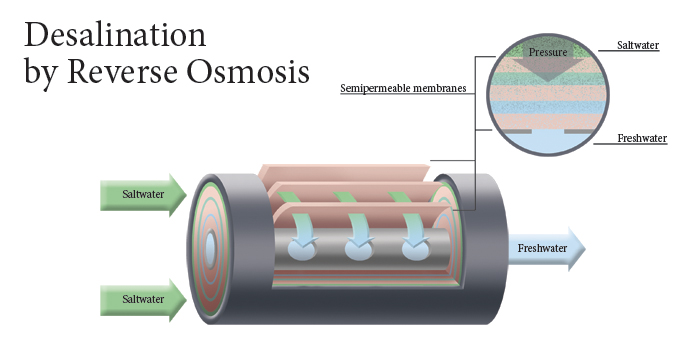

The plant that might be dead would suck in nearly 70 gallons of seawater a second. Water would whoosh through a 12-foot-long tube-shaped screen suspended about 10 feet above the seafloor, just past the kelp forests that hug Santa Cruz’s shoreline. The screens would block critters larger than two millimeters wide.

|

Illustration: Leah Hammon |

Pumps would pull water onshore through a pipe nearly three feet across. Then, at the desalination plant itself, water would shoot through fine-grained filters, leaving the salt behind in a process called reverse osmosis. The plant would generate about 3.8 million gallons of briny waste each day. The discharge would mix with the city’s treated wastewater and return to the ocean, with a final salinity akin to saltwater.

Energy tops the concerns of nearly everyone involved. In a year, the proposed plant would consume about 10 million kilowatt-hours of electricity and emit about 3,500 metric tons of carbon dioxide—a calculation that includes power and associated costs such as delivery trucks. The City Council pledged to keep the plant “carbon neutral” by adding solar panels to city structures and purchasing about 2,000 metric tons per year of certified emissions offsets.

But that’s not adequate, says Longinotti, who now leads the group Desal Alternatives. Say you pay a logger not to cut down trees, he says. Does that reduce the demand for wood or paper? “The whole offset concept is fraught with really dubious claims,” Longinotti maintains.

Other activists cite the plant’s potential to spur population growth as a key problem. More water means more people, they say. Water would allow the university to balloon, jamming city streets and exhausting its resources. The issue strikes at the center of the discord: Does the city really need more water? Or could it get by on what it has now?

The answer has three key ingredients: rain, fish, and people.

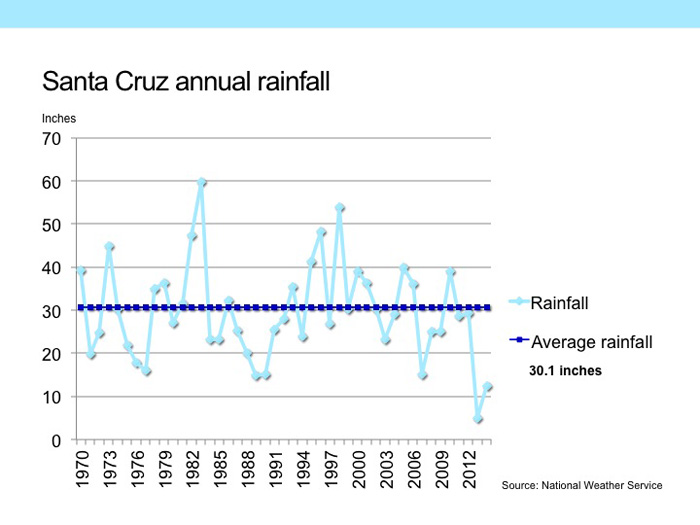

Start with rain. During most winters, there’s no problem; the city averages 31.35 inches of rainfall a year. The San Lorenzo River surges, providing ample water for both salmon and the city’s pipes. The city funnels some of this flow into Loch Lomond, which usually swells to its full 2.8-billion-gallon capacity. That’s enough to carry the city through the dry summer months.

Loch Lomond can withstand one dry winter. More than that, however, spells shortages. And this year’s total of 13.55 inches redefines dry. To cope, Loch Lomond will shrink to “a really scary place,” says Don Lane, the city’s vice mayor. “Then we cut back in ways we haven’t seen before. The daily life of the community gets truly disrupted.”

|

|

Graphics: Becky Bach |

Climate change may worsen the city’s plight. A 2012 U.S. Geological Survey study predicts shorter winters, longer summers and more variable rain in the Santa Cruz Mountains. Even if total precipitation remains steady, the city would need more water to squeak through a lengthy dry season.

Next, figure in fish. To suss out the city’s supply, subtract the minimum “fish flows” young salmon need to reach the ocean in the spring and then return as adults several winters later to lay eggs upstream. The city has been negotiating these levels with state and federal fisheries agencies since the 1990s. All agree the fish need more water than they have now. A deal might take effect before fall 2014, according to Chris Berry, the city’s watershed compliance manager.

Severe drought makes the debate moot. “This is that year in your career as a fisheries biologist you hope you never see,” says Jon Ambrose of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. “If there’s no water in the creek, all of the conservation in the world isn’t going to help.”

Dry decisions

Conservation seems the simplest solution to the city’s water worries.

Santa Cruz residents use 100 gallons per person per day, on average, one of the lowest per capita rates statewide. That’s just over 3 billion gallons per year. Annual demand peaked in the late 1990s at nearly 4.5 billion gallons, but dipped following the recession and several major business closures. “For about 30 years, all it’s been doing is wiggling,” consultant Bill Maddaus told the city’s Water Commission in March. That’s good, he said. Although the city grew, its water use remained unchanged.

Maddaus and his colleagues recently analyzed 39 new conservation measures—ranging from washing machine rebates to landscape retrofitting. The proposals would save a few hundred million gallons a year, enough to maintain the holding pattern as the city—and university—expands. “On a long-term basis, the best we can do is hold even,” Maddaus says.

Yet the city’s most ardent environmentalists advocate radical cutbacks. “We feel like Jeez Louise, why don’t we try to live within our limits?” Patton says. That approach underlies the philosophical gap between desalination supporters and those against it. The city shouldn’t need more water. Just use what’s there, no more.

Kocher heard that argument often. “The problem is when you are in charge of the delivery of a resource—something as important as water—you really can’t be risky with that,” he says. “The trick is you have to run a water agency in accordance with what the statistics say demand will be, not what people wish it would be.”

Podcast produced by Becky Bach. Click on arrow to play.

The city has examined other alternatives. During wet years, Santa Cruz could transfer some of its San Lorenzo water to the neighboring Soquel Creek Water District to recharge its overdrawn aquifer. Then, in dry years, Soquel could return the favor. But the aquifer needs years to recuperate; until then, only Soquel Creek would benefit. These trades would require costly pump and piping upgrades as well as a touchy renegotiation of water rights with the State Water Resources Control Board.

Water trading has an evident drawback: Transferring water requires water to transfer. In a prolonged drought, there might not be water for anyone.

Santa Cruz also might supplement supplies by recycling wastewater, although it is now illegal to directly reuse treated wastewater. “The next front is to allow it to be used in surface reservoirs that are later used for drinking,” says Richard Mills, who leads water recycling and desalination efforts for the California Department of Water Resources. The state plans to release new recycled water regulations by 2016.

A dry future?

For now, Santa Cruz residents are coping with mandatory cutbacks of 25 percent, which took effect May 1. Stricter rationing may be in store. “This year is going to be a great test,” says Rick Longinotti. “We’re going to get a real live experiment in who is going to suffer and how much.”

Meanwhile, a new 14-member city advisory committee will examine water supply alternatives. If the group recommends a desalination plant—though few think that is likely—the earliest eligible election to approve desal is spring 2016, pushing the plant’s opening beyond 2020. Dry winters could stretch the endangered coho salmon and the parched community to their limits.

As longtime water commissioner Andy Schiffrin asks: “Is the community willing to live with [desalination’s] costs and impacts, or does it really want to see its lifestyle changed in a very significant way in times of drought?”

While debate drags out for decades, the members of the city council, the water department staff, and the activist community all shift. It’s a phenomenon Kocher knows well. “Every four to eight years, it’s a whole new cast of characters and suddenly you are right back where you were,” he says. “We’re a funny community like that. I don’t know how you get anything done.”

Sidebar: Desal in Action

A grating roar escapes through an open door of a small building tucked beside Highway 1. It’s the only hint the structure houses one of California’s few municipal desalination plants.

Since 2005, the Sand City Water Treatment Facility has transformed salty water buried below the nearby beach into supplemental drinking water for the businesses and 350 residents of Sand City, a cluster of shops and hotels north of Monterey. Like Santa Cruz, Sand City must reduce its reliance on river water, says Anthony Lindstrom, a supervisor for the plant’s operator, California American Water.

For a desal plant, it’s tiny. It can produce about 100 million gallons of freshwater per year—just one-ninth the capacity of the plant eyed by Santa Cruz leaders.

Next to the plant’s door sits a basket of earplugs. White hard hats fill a box nearby. Fluorescent lights illuminate a maze of metal pipes connecting tanks of all sizes. Many sport primary-colored labels—1450 GAL, CO2 feed, SODIUM HYPOCHLORITE. Water drips from the piping, pooling on the concrete floor. “If the water is saltier, the pressure needs to be higher,” shouts foreman Robert James above the din.

Like most modern desalination plants, the Sand City facility removes salt by pushing water through fine-meshed membranes in a process called reverse osmosis. The membranes resemble layers of cardboard coiled like wrapping paper into a tube. Water squeezes through the pores, leaving the chubby sea-salt molecules behind. Pumps power the separation, gobbling energy and emitting an all-encompassing akkakkakkakkkakk that tops 100 decibels—as loud as a good seat at a rock concert. It takes 9,000 kilowatt-hours of electricity to desalinate one million gallons of water, pushing the plant’s average monthly utility bill above $13,000, Lindstrom says.

Although the membranes strip salt from the water, other treatments boost it to drinking water standards. First, pre-filters remove dirt and other coarse materials. Chlorine and ultraviolet radiation disinfect the water before it heads outside, bubbling up through a giant vat of white calcite crystals. The reverse osmosis membranes are so effective they strip out all minerals, leaving the water undrinkable. The calcite raises its pH. Water leaving the plant is then mixed with water already in the community’s pipes.

The Sand City facility may soon have company: At least 33 plants are in the planning stages statewide. By 2016, the massive Carlsbad Desalination Project should crank out 50 million gallons per day for people in and near San Diego.

© 2014 Becky Bach / UC Santa Cruz Science Communication Program

Top

Biographies

Becky Bach Becky Bach

B.A. (biology and government) Wesleyan University

M.S. (ecology) University of California, Davis

Internship: Stanford University School of Medicine

My mom taught me how to write at the kitchen table of our Kansas home. I hated every minute of it. I’d rather have been playing soccer or exploring the wilds of suburbia.

Somehow, I stumbled onto the staff of my college newspaper. Having a press pass squashed my self-consciousness. It was a license to ask interesting folks almost anything, and I thrived on the paper’s esprit de corps. When I left academia, I yearned to share my neat new knowledge; science journalism was the career for me.

But first, I had more exploring to do. After stints at several newspapers, a winter monitoring the homeless, and five adventurous years as a park ranger, I’m ready to return to writing. This time, I’m seeking stories with curious characters, critical research and, most importantly, real-world implications.

Becky Bach's website

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Fiona Lee MacLean Fiona Lee MacLean

B.A. (environmental studies) Connecticut College

Internships: Sea Birds Lab, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution; Seymour Marine Discovery Center and Younger Lagoon Reserve, UCSC

My work as a naturalist taught me the importance of science illustration. I was always pushed to find new ways to connect myself and others to the outdoors. Using my trusty drawing habit to focus attention, I developed a keen sense of art as a tool for deepening observation, strengthening connections, and fostering curiosity.

I am dedicated to a life outside and I am intent on fueling a similar passion for the outdoors in others. I look forward to working toward this goal by illustrating nature in situ for research expeditions, institutions, and personal thru-hiking projects.

Fiona MacLean's website

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Leah Hammon

B.A. (archaeology) Boston University

I never expected to do anything serious with art. It was always just a hobby: doodles in notebooks and a few elective classes in high school. I went into college undeclared, with little clear idea of what I wanted to do. I ended up fascinated by archaeology, and went to a field school in Guatemala, working on a dig at a Maya site. I drew soil and architecture profiles as well as several burial excavations. I really enjoyed creating those drawings and began researching science illustration; I am excited for future opportunities to pursue this career.

Leah Hammon's website

Top |