|

| Illustration: D.J. Jackson |

Organic coffee is touted as an ecological boon, but there's a darker reality, as Nsikan Akpan reports. Illustrated by D.J. Jackson.

It starts with a patter. A few raindrops splat against broad jade leaves as Penelope Gillette treks through the jungles of Soconusco, Mexico. The 22-year-old quickens her pace, deftly navigating the slick moss as she descends the hillside.

Tempests strike daily during the rainy season here. Neither Gillette’s poncho, the tree canopy, nor the surrounding 6-foot-tall coffee shrubs will protect her from getting soaked. She and her two field guides beat the deluge and arrive at their field station, where she will log her field recordings on one of the rainforest’s smallest critters: the ant.

Rainforest ants help Gillette navigate the fraught realm of Latin American coffee cultivation. Her daily treks into the Mexican jungle were commissioned by Stacy Philpott, a UC Santa Cruz agroecologist who measures the ecological and economic costs of growing the beans. “Most people drink coffee, but very few people think about where it's cultivated or where it comes from,” says Philpott—especially the “organic” or “fair-trade” certifications so common at urban coffeehouses today.

People love organic and fair-trade coffee because they pair caffeinated warmth with environmental and social altruism. These gourmet brands avoid synthetic pesticides and offer better payouts to farmers, respectively, yet neither necessarily protects against the substantial deforestation linked to coffee cultivation. Driven by price fluctuations and outbreaks of crop diseases starting in 1970s, farms across Central and South America intensified production with “sun coffee”—higher-yielding crops grown in orchards without a natural tree canopy. Farmers—whether organic, fair-trade, or commercial—bought into the system, but neither the growers nor ecologists realized how this radical shift would affect the biodiversity hotspots that border most coffee farms.

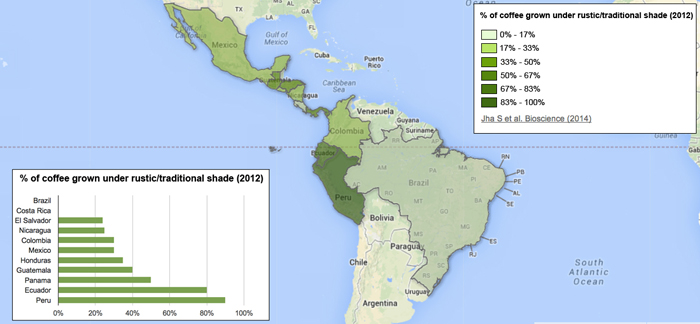

A recent survey of 19 major coffee-producing nations found that nearly half their farms have completely eradicated their original tree canopy. Brazil—the top producer of commercial, non-organic coffee—raises 90 percent of its supply with zero shade. Mexico, a leading supplier of organic brews, is considered a modest adoptee of sun coffee, growing only 20 percent—150,000 hectares—without tree cover.

But deforestation may ultimately cost farmers by displacing its tiniest creatures, such as ants. For Philpott, the farms’ abundant ants are six-legged mascots for eco-friendly agriculture that retains forests. They can reveal when soils become poor and can build cooperatives with other insects that make farms more successful. Ants may be small in stature, but her work shows they carry big value for a more sustainable future.

A slice of Ireland

Philpott leads annual expeditions from Northern California to the sweltering core of Mexico’s coffee empire, the southern state of Chiapas. Agriculture is the Chiapan lifeblood. Indigenous people began sowing corn on its fertile lands in 1500 BCE. Over the centuries, they added sorghum, soybeans, cacao, sugar cane, bananas, palm oil, and coffee—lots of coffee. Chiapas grows more than half the coffee in Mexico, which ranks within the top ten of global producers, with an annual output of 250,000 tons of coffee beans.

Dawn breaks, and Philpott’s team gathers for breakfast on the field station’s patio at Finca Irlanda, a 320-hectare coffee farm perched near the Sierra Madre mountain range. Finca Irlanda, or the “farm of Ireland,” was a pioneer in sustainable farming. It was the world’s first plantation to receive biodynamic certification in 1967. The forested plots prevent erosion and shelter wildlife—more than 240 bird species, 64 species of mammals, and 70 tree species. Fields of sun coffee garnish the farm too, making it ideal for comparing shaded versus unshaded cultivation.

|

| Click on map to see a larger version. |

Graphic: Nsikan Akpan |

When Philpott began her graduate studies at the University of Michigan in 1998, she knew three things would make her happy: insects, agriculture, and the tropics. Her advisors, John Vandermeer and Ivette Perfecto, had just returned from Southern Mexico, and couldn’t stop talking about it. They invited Philpott along the next season.

Philpott, a native of the Indianapolis suburbs, loved it from the beginning: “It was my first exposure to the ecological and social impacts of coffee, and I’ve gone back every year since,” she recounts.

“Stacy has done some ground-breaking research with regard to arboreal—twig-nesting—ants," Perfecto says, especially with the basic ecology of species assemblage or how organisms push, pull, fight, scratch, or help each other. These bestial societies define the livelihood of the habitat—and the coffee farm.

The drive to the field station begins by passing rows of commercial coffee estates until the paved road turns to rocky dirt. Even with four-wheel drive, the excursion up the mountains takes two hours, unless the hillside has washed into the road. Upon arrival, it’s best to keep one’s boots on. Poisonous coral snakes often crawl along the bedrooms and research labs of the field station. Then there are the rats, gigantic and always battling for the facility’s provisions of avocados. From this wilderness, Philpott’s team has tracked the lifestyles of tiny invertebrates crawling and buzzing around the region’s coffee plantations.

Ant security

Philpott quickly discovered these arthropods weave a protective vest over coffee landscapes. Her investigations showed that ants kill a buffet of coffee pests, including coffee borer beetle, which causes $500 million in crop damages worldwide each year. These services are not done pro bono. Rather, the ants get their compensation in honeydew harvested from green scales—flat bugs that cover the branches of coffee bushes. “If you hit a tree, they'll start swarming because they're that aggressive,” says Gillette of Azteca ants, a fierce protector of green scales.

Gillette and Kate Ennis, a doctoral student in Philpott’s lab, spent summer 2013 surveying habitats at different elevations. Ennis uses wax to make fake tree nests, which look like muddy bee hives, and then watches as two ant species engage in mortal combat for the new home. Or she places tuna with oil, which they love, in the middle of a field and then records ants as they arrive for the feast. The work is part of Ennis’s broader look into the community structure of coffee plantation ants and how these communities help control pests.

|

|

This slideshow of images from Penelope Gillette, assembled by Nsikan Akpan, shows the Chiapas research setting studied by UCSC's team. |

“The way they walk allows me to distinguish between two species,” says Ennis. “Some walk really quickly, while others walk really slow. Some sort of swagger or swivel their hips, while others crawl stiffly like big Tonka trucks.”

Philpott’s group has shown that when coffee habitats lose shade trees, these societies take a major hit. As a young scientist with the Smithsonian Institution’s Migratory Bird Center in 2005, she observed a frantic turf war between arboreal ants following tree pruning. After crashing to the earth, the survivors return to their former trees and scramble up the trunks, so they can build new nests. She found that Azteca ants don’t rebound as well as another species, Camponotus textor. Azteca ants are more savage defenders against the coffee berry borer and caterpillars, so tree pruning ultimately tarnishes the natural shield against pests.

Azteca ants aren’t the sole patrollers. During a 2013 investigation of eight tree-dwelling species, Philpott was part of a crew that found removing a single variety doubled the amount of coffee berry borer beetles in most cases. “A high species diversity of ants is important for their function as predators, so if you have fewer ant species, they're not as good at controlling pests,” Philpott says.

Ant communities also change in response to soil quality, according to an investigation by her student David Gonthier. Green scales flock to coffee plants rooted in top-notch soil enriched with nitrogen. Another ant species—Pheidole synanthropica—takes notice of the extra honeydew makers and clambers onto plants in better soil. Heartier plants mean more green scales—and more ants to dine on it all.

Bird beginnings

Coffee intensification and deforestation disturb nature’s cornucopia for more than just ants. Insect and bat pollinators flee. Rare orchids and ferns, which hang from tree branches, fall victim to the axe’s blade too. Furry mammals like coatis, kinkajous, and anteaters suffer their habitats’ destruction. But the biggest losers are undoubtedly songbirds.

Ecologists began recognizing the ecological damage wrought by sun coffee when migratory bird population in the U.S. and Canada nose-dived in the 1980s. Scientists rallied—and the U.S. Congress followed suit. “The argument was simple. The U.S. is an agricultural power, and you need insectivorous birds to control pests on your farms,” says Peter Bichier, a field ornithologist on Philpott’s team who joined the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center (SMBC) soon after it was commissioned in 1991.

SMBC ornithologists Russ Greenberg and Gene Morton led bird censuses from Panama to Chiapas in the 1990s. As they trekked from low-lying deltas to the highlands, they noticed that birds loved to roost in coffee plantations. Forest birds congregated in the coffee plantations with canopies that mimicked the regular rainforest. “A 20-hectare area in Chiapas had about 135 species of birds. It was just incredible,” says Bichier, who has the countenance of Paul Newman and the sturdy yet limber frame of a man who started hacking paths through underbrush as a rainforest guide in his early 20s.

The findings spurred SMBC to create a new specialty certification that would preserve wildlife. Bird-friendly coffee became the newest member of the gourmet coffee market in 1998. Unlike an earlier shade certification provided by the Rainforest Alliance, the SMBC criteria were founded on organic principles and had stringent requirements for the tree canopy. “We went to many certified organic farms during our survey, and there was hardly any shade. Back then, an organic label might have a nice jaguar on it, but I can guarantee you, there were no jaguars around there,” Bichier says.

The coffee you’re not drinking

Though widely considered better for the environment than organic, shade-certified coffee hasn’t mustered wide appeal. Of the 400 billion cups poured each year, one out of ten are specialty brews—and shade coffee only represents a sliver of that already small percentage. A 2010 poll by the National Coffee Association found that 75 percent of coffee drinkers had never heard of the SMBC or Rainforest Alliance brands, while only 6 percent had purchased them.

Podcast produced by Nsikan Akpan. Click on arrow to play.

The popularity barrier may fall on the side of producers as well. From the 1990s to 2010, the percentage of shade farming decreased in most Latin American countries. Meanwhile, some farms adopt shade cultivation, but skip the certification process.

Lorena Calvo, a farm owner in Guatemala, is one example. Her farm doesn’t hold organic or fair-trade certifications because “they are too expensive.” The extra business from the eco-labels does not cover those costs at current market prices. But as a former biologist, she knows that retaining trees saves habitat and migration corridors for animals.

Some gourmet coffee shops in the U.S. and Europe make a special point of finding these uncertified farms because shade produces better tasting coffee, according to studies. “We have two farms in Boquete, Panama that literally go right up to protected wildlife rainforests,” says Jesse Crouse, head of product development at the Santa Cruz-based Verve Coffee Roasters. “These farmers understand what is needed to produce coffee without messing up the ecosystem or future possibilities for that rainforest.”

Crouse flies across Central America with coffee exporters to track down shade-conscious small farmers. “I would say at least 60% of our coffee overall and about 90% of our Central American and South American coffee would be considered shade-grown,” says Crouse. “We pay very good premiums, sometimes triple the amount of a fair-trade minimum or market price,” says Crouse.

The tree spectrum

But are uncertified markets best for nature and farmers in the long run?

“Well, it's all about trust,” says Chris Bacon, an environmental sociologist and agroecologist at UC Santa Barbara. Traveling to Mesoamerica may build a powerful connection between importers and farmers, but on a broader scale, certifications add accountability. “Some roasters and buyers can show you the evidence, but SMBC developed a scientifically-based certification over decades that's comparable across Latin America.”

Philpott agrees. “If I took my mom to a coffee farm anywhere in the tropics, she would say, ‘Wow, this is a jungle!’ But could she tell if this shade coffee is good enough to protect biodiversity?”

When Philpott joined the SMBC team in 2004, she examined the sustainability goals of fair-trade and organic certifications. She found that those certifications didn’t necessarily protect as much biodiversity as nearby farms that met shade certification criteria. On the other hand, organic and fair-trade farmers earned higher—even though their plantations hosted fewer species of wildlife.

Even so, a diverse tree landscape can yield income when coffee prices dip, which they regularly do. Many shade farmers plant crops, such as banana or plantain trees, to supplement the natural canopy. Some farmers also grow timber species and sell the wood, sustainably.

Estelí Soto, a native of Chiapas and graduate student in Philpott’s lab, is exploring how shade trees retain natural networks of pest control. She tracks other enemies of the coffee berry borer, namely parasitoid wasps. These winged insects dive-bomb the borer’s larvae and inject eggs into them. It’s a fatal blow for the borer. Estelí Soto, a native of Chiapas and graduate student in Philpott’s lab, is exploring how shade trees retain natural networks of pest control. She tracks other enemies of the coffee berry borer, namely parasitoid wasps. These winged insects dive-bomb the borer’s larvae and inject eggs into them. It’s a fatal blow for the borer.

In the past, Mesoamerican coffee developers have released the wasps onto their farms to stymie borer outbreaks, but the predators have not established a foothold. Soto suspects that ants may explain why. “Everyone is on the same tree, battling for the same branch,” Soto says. She thinks the ants may mistake the wasps as a threat to the honeydew-producing green scales. The overprotective ants then attack the wasps, sabotaging the introduced methods of pest control.

For Soto, biocontrol research bridges the motivations of ecologists who want to build sustainable argoecosystems and the desires of farmers. Coffee producers are innately inquisitive about the biology that supports their endeavors, she says. They often ask scientists about insect pollinators or why traditional agrosystems like milpa are so successful. And once growers learn a new fact, they eagerly adapt the principle for their benefit—and the ecosystem’s. “After learning ants assist pollination, one farmer started tying strings between coffee plants and trees to let them travel from place to place,” Soto says.

After she finishes her doctorate, she wants to establish research facilities in Chiapas where farmers can learn about parasitoids and other natural tools of pest control. But her plan, along with broader sustainability for the coffee region, will depend on shade trees. Coffee intensification and tree loss reduces the abundance and diversity of parasitoid wasps too.

Most Mexicans appreciate the value of having coffee under shade, but the challenge is keeping those perceptions intact when prices fall, Soto says. “People who live off their plantations see the coffee as a provider for the house, but also care for their land like kin,” says Soto. They’ve done so for generations—and they want to keep it that way.

__________

Sidebar: Certifiable Picks

Each coffee certification program has different goals. Here is a quick rundown of the major ones, courtesy of Stacy Philpott of UC Santa Cruz.

Organic Certification

Like organic certification of any kind, the criteria for coffee focus on eliminating synthetic agrochemicals and promoting soil quality. Genetically modified crops are banned too. Primary objectives revolve around how to terrace farms to slow soil erosion and how to develop alternative control methods for weeds and pests that do not include synthetic herbicides or pesticides.

Fair-Trade Certification

Fair-trade certification addresses the socioeconomic needs of coffee farmers. By insuring a baseline price equal to a living wage, farmers can support the communities where they live. Most farmers obtain fair-trade certification by joining cooperatives. The cooperatives receive the price premiums connected with the label and dole the extra revenue into the community to pay for schools, clinics, and better roads. The social outcomes take priority. Fair-trade brands carry ecological standards on occasion, restricting many toxic pesticides and herbicides, while permitting some synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, fungicides, and herbicides.

Shade Certification

In this newest brand, the criteria address the vertical complexity of the farm. Two brands exist: Rainforest Alliance and Bird-friendly. Rainforest Alliance doesn’t require organic certification and is more popular due to less stringent requirements with tree diversity. Bird-friendly, operated by the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center (SMBC), is the most eco-friendly specialty certification. It requires organic cultivation and a complex tree structure based on the number of species, their heights, and how often the trees fruit or flower. This rigor ensures the most diverse rainforest habitats.

© 2014 Nsikan Akpan / UC Santa Cruz Science Communication Program

Top

Biographies

Nsikan Akpan

B.A. (biology) Bard College

Ph.D. (pathobiology and molecular medicine) Columbia University

Internships: Science News, National Public Radio

The mind is where our dreams lift us, where our terrors haunt us, and where every concept of human existence and the universe originated. Who wouldn’t want to learn more about how it works?

Science was always my muse, but in college I became enchanted with the brain. I witnessed mental disease drain the essence from loved ones and the grandparents of friends. It astonished me how the brain can work so elegantly, then suddenly grow so fragile. This juxtaposition drew me toward doctoral studies on therapies for stroke and Alzheimer’s disease.

My voyage through scientific research also took detours into immunology, ecology, and even geophysics. But I decided I'd rather explore these mysteries with words on a page—and in my mind, as it rambles through the landscape of scientific discovery.

Nsikan Akpan's website

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

D.J. Jackson D.J. Jackson

B.A. (visual art) Eckerd College, St. Petersburg, Florida

Internship: University of Queensland, Australia

I attended Eckerd College to fulfill my passion for science, but while I was there I felt I needed to make a choice between science and art. After graduating I found out that I could pursue both and made my way out to California to study scientific illustration. Now I'm off to explore and illustrate the amazing things nature has to offer.

D.J. Jackson's website

Top |