|

Santa Cruz resident Dan Shapiro holds a vial full of the eggs of an intestinal whipworm, right before drinking it in Italy. Photo courtesy of Dan Shapiro. |

Would you infect yourself with parasites to treat a stubborn ailment? Julia Calderone slithers through the science. Illustrated by Jessie Jordan.

As Amy Stamm’s flight descended into San Diego, she was more excited than nervous. Ineffective treatments for multiple sclerosis had scarred her legs and hips with permanent craters. Now, an enticing new option lured her to cross the border into Mexico. A man picked her up from the airport, and together they zoomed to Tijuana. At a stripped-down medical office, a Mexican doctor sucked a clear liquid out of a vial, squirted it onto gauze, and taped it to the inside of her arm. Within a few minutes, her skin began to itch.

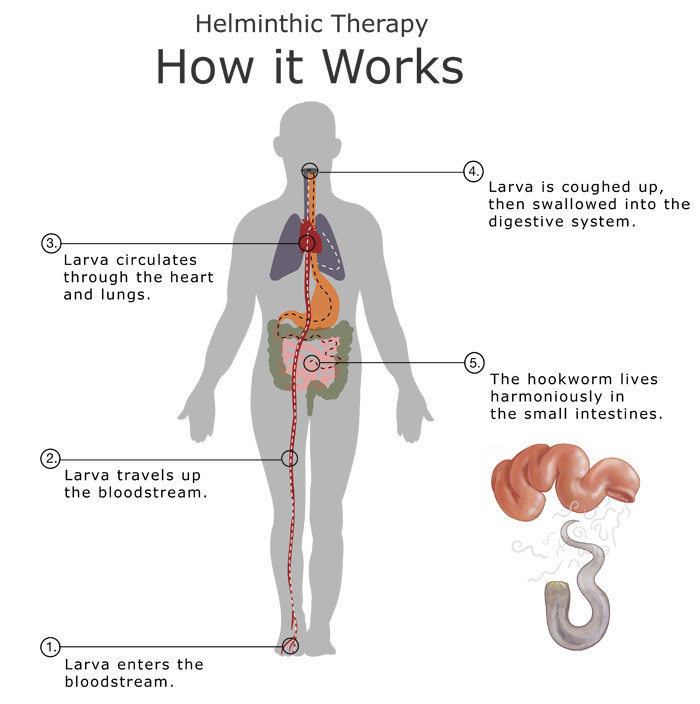

When Stamm removed the bandage that evening, she counted 35 red dots. Now all she had to do was wait five days for the 35 hookworms to circulate through the chambers of her heart and break into her lungs. Then she’d cough them up and swallow them into her gut.

Stamm is just one of possibly thousands of U.S. citizens who have infected themselves with parasitic worms, or helminths, in desperate attempts to restore their health—a therapy illegal in this country. Several studies hint that these worms may help calm allergies and other conditions, but the medical establishment isn’t yet sold. Even so, success stories—fueled by online chat groups and a few charismatic adherents—keep driving more people to become helminth hosts.

Obsession with cleanliness

American parasitologist Charles W. Stiles reported in 1902 that he’d found the “germ of laziness,” as severe hookworm infections caused anemia and weakened immune systems. John D. Rockefeller responded by forming a commission to eradicate hookworm from eleven states across the American South in 1909. Within five years, the parasite was essentially eliminated.

But a 1989 study by British epidemiologist David P. Strachan hinted that as industrial countries became more sanitary—with flushing toilets, cement sidewalks and well-regulated food industries—allergy rates skyrocketed. Because poorer, less-developed regions seemed to remain mostly allergy-free, Strachan postulated that cleanliness was somehow making people sick. Nearly ten years later, a 1998 study of about half a million children ages 13 to 14 in several dozen countries seemed to support Strachan’s hypothesis: people in English-speaking, Western countries appeared more asthmatic than others.

The “hygiene hypothesis” exploded. It not only seemed to explain the recent surge in allergies—which now affect 50 percent of industrialized human populations—but it potentially clarified the swell of other autoimmune and inflammatory conditions such as multiple sclerosis, inflammatory bowel diseases, lupus, type 1 diabetes and eczema. Some scientists believe even autism could arise in this way. The “hygiene hypothesis” exploded. It not only seemed to explain the recent surge in allergies—which now affect 50 percent of industrialized human populations—but it potentially clarified the swell of other autoimmune and inflammatory conditions such as multiple sclerosis, inflammatory bowel diseases, lupus, type 1 diabetes and eczema. Some scientists believe even autism could arise in this way.

Joel Weinstock is trying to find a gut-level explanation for these patterns. Now a gastroenterologist at Tufts Medical Center, Weinstock wondered in the early 1990s whether alterations in the gut’s flora—our complex ecosystem of billions of intestinal bacteria, fungi and protozoa—may cause our immune systems to misbehave.

“When you poop in the toilet, most people look at that brown item and think it’s just waste. But it’s actually about 50 percent bacteria,” says Weinstock. “They’re basically a living organism, producing vitamins and toning the immune system. They’re important.”

Repeated exposures to viruses, bacteria and probiotics program our human immune system when we are young. Such exposures instruct our cells to mount two types of immune responses: the "fight and kill" response, which causes inflammation and attacks foreign invaders, and the regulation response, which tamps down angry cells after their attack. But in extremely clean environments, where our immune systems aren’t acquainted with a broad array of foreign organisms, the regulation response can break down, says Weinstock.

“If something that gets in your body can be killed with a fly swatter, but your immune system decides to use the atomic bomb, that’s not going to be very good for your lungs, skin or other organs,” says Weinstock. This is what happens during an autoimmune disease—the body attacks itself.

Research teams eliminated possible man-made immune-wrecking culprits in the 1990s, like vaccines, specific types of food, and environmental contaminants. But Weinstock took a different approach. He “turned the mirror backward” and hunted for bugs we’ve cleaned up—bugs that, at one time, might have coexisted with us and kept us healthy.

Weinstock figured that most people in hyperclean environments are still exposed to viruses and most classes of bacteria. But helminths—these tiny worms that have evolved in animal guts for aeons—vanished when autoimmune diseases spiked in the late 20th century. Could their disappearance have left our immune systems unbalanced and confused?

Worm safety

A slew of animal studies in the 1990s suggested that helminths seemed to regulate the immune system by calming the inflammatory attack response. Weinstock wondered how helminths might alleviate symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. In humans, IBD symptoms can include abdominal pain, bloody stool, fatigue and a decreased sense of well-being. Weinstock exposed young mice with IBD symptoms to a variety of helminths, and found that infection seemed to reduce the chances of intestinal inflammation.

|

Illustration: Jessie Jordan |

But could helminths be safely used in humans? Weinstock’s team identified a parasite that pig farmers constantly encounter without falling ill: Trichuris suis ova (TSO), the eggs of an intestinal whipworm that lives in pork.

At the University of Iowa in the late 1990s, Weinstock gave a slightly salty cocktail of microscopic TSO to seven patients with Crohn's disease for three months. Three patients went into remission. The remaining four had significantly reduced symptoms.

In 2004, 29 patients with Crohn’s drank live eggs for six months. Nearly 80 percent reported a decrease in symptoms, and 72 percent fell into remission. None reported side effects. With the FDA’s blessing, Weinstock then teamed up with the pharmaceutical company Coronado Biosciences, which expanded the studies.

“Nobody got hurt, nobody’s eyes fell out,” said Weinstock. “But it’s still too early to say, ‘Well golly gee, this is going to be better than apple pie.’”

Jorge Correale then published a series of dramatic observations from Argentina in 2007. He followed two groups of 12 people with multiple sclerosis (MS)—a debilitating disease where a person’s own immune system eats away at the protective lining of their nerve cells. One group had active helminth infections, and the other was parasite free. After almost five years, MS activity in the group with helminths had virtually ceased. The non-infected group’s activity worsened. When four subjects later decided to eliminate their parasites, their MS symptoms reappeared.

These results excited MS researchers. John Fleming, a neurologist at the University of Wisconsin, began the first MS-related clinical trial using TSO in the U.S., which was published in 2011. Five newly diagnosed MS patients drank TSO every two weeks for three months. Throughout the study, Fleming monitored new and old lesions, or spots of nerve damage, with MRI scans. Fleming found that lesions fell more than three-fold by the end of the study. When patients stopped drinking TSO, their lesions jumped back up to their original levels. But in a second and longer phase of the study, which Fleming described in April at the American Academy of Neurology meeting, he found only a modest decrease in lesions in 15 patients taking TSO.

Another scientist encouraged to explore TSO was Dario Siniscalco, a biochemist at Second University of Naples, Italy. Siniscalco and others believe that autistic children have imbalanced immune systems—specifically, leaky gut, a disorder where the barrier of the intestines is damaged. Siniscalco and colleagues have treated almost 50 autistic children with TSO in the past three years. While he is still working to publish the results, he is thrilled by his early observations.

“Our kids [have] improved sociability and attention,” says Siniscalco. “They are able to follow and fix attention better than before the treatment.” They also became calmer, he says.

Podcast produced by Julia Calderone. Click on arrow to play.

Typhoid Mary

While scientists around the world were scrutinizing helminthic therapy systematically, Jasper Lawrence was constructing an underground business selling worms online.

Lawrence’s family immigrated from the U.K. to upstate New York when he was four. He recalls hovering over a humidifier with a tea towel on his head, suffering his first bouts of asthma and allergies. When he moved to Texas, his allergies turned violent. After running through a field of Timothy grass, his eyes swelled shut; his brother had to lead him home by the hand.

Later he moved to Santa Cruz, where he led the life of a wild child running barefoot through Ben Lomond. The soles of his feet were so tough he could extinguish cigarette butts with them and walk on brambles. He drank out of streams and slid down banks into thick clouds of dust that coated his lungs and mouth in dirt.

“I got a spectacular case of the shits and the pukes after drinking out of a puddle when I was nine,” Lawrence says. “A horrible green foul smelling vile substance coming out of both ends.”

This intense rapport with nature, he believes, temporarily relieved his allergies. But after moving back to the U.K. to live with his aunt when he was 13, his allergies returned. Lawrence went back to Santa Cruz at 23, married and had five children. When he was 27, he got stung by bees and went into anaphylactic shock. He later developed asthma that made him bark like a sea lion.

By the time he left his wife and moved back to the U.K. in 2004, he had become dependent on Prednisone, a drug commonly prescribed to treat allergies. He gained so much weight that he stopped weighing himself at 200 pounds. Shocked, his aunt mentioned a BBC documentary she had seen on helminthic therapy. He hopped on the computer to do research and didn’t budge until 3 a.m. Then and there, he decided to fly to Cameroon to infect himself with a parasite.

After identifying the most heavily used latrines in a Cameroon village, he bought two liters of palm wine, gathered piles of human excrement, watered it down, and crisscrossed the feces-laden area with his bare feet in 100-degree heat. A few nights later, he awoke in the middle of the night with a violent coughing attack that almost caused him to vomit. He had infected himself.

|

|

Illustration: Jessie Jordan |

|

The following spring, he burrowed his face into a cat and didn’t have a violent allergic reaction. After reading about Correale’s success treating MS, Lawrence kickstarted Autoimmune Therapies in the summer of 2006, an online business selling whipworm and hookworm for $2,000 to $3,000 per treatment.

When Lawrence first wrote about his self-infection and his business online, the response was violent and polarized. Some accused him of being a “modern typhoid Mary,” reintroducing a terrible scourge that had been eliminated. But to other, more desperate sufferers of incurable diseases, he signified hope.

“I’m generally not viewed in moderate ways. I’m either some kind of pariah or a messiah. And they’re equally disturbing, because of course I’m neither,” says Lawrence.

Lawrence had never studied medicine; he lacked even a college degree. He sought the expertise of his brother-in-law at the time, Marc Dellerba, who had a Ph.D. in chemistry and a master's in clinical biochemistry. Dellerba did an extensive review of the scientific literature to ensure the therapy’s safety and effectiveness, and Lawrence cultivated the worms by recreating the tropics in a bucket.

“What I most wanted was to not make someone ill. So I exercised what I thought was very high degree of caution surrounding this issue,” Lawrence says.

Lawrence and Dellerba originally teamed with Jorge A. Llamas, an alternative therapies doctor, and Garin Aglietti, another self-infected believer. They had patients fly into southern California and cross into Mexico for treatment. But this partnership ended shortly after its inception, and Lawrence continued to sell worms solo in Santa Cruz.

Llamas and Aglietti formed their own company, Worm Therapy, in Mexico. Today, one of Llamas’ patients is Amy Stamm.

|

|

|

Amy Stamm's arm shows the marks of burrowing hookworms after she infected herself in Tijuana. Photo courtesy of Amy Stamm. |

Stamm's doctors had originally put her on Copaxone, an MS drug that not only seared as it entered her skin, but chewed away at the fat cells near the injection site. When her MRI results worsened, her doctors switched her to an immune-boosting drug called Rebif, a brand of interferon, which covered her in bruises, disrupted her thyroid functioning, and gave her a fever. Waves of numbness coursed through her hands, her muscles spasmed, and she was exhausted.

In 2011, she learned about helminthic therapy from a coworker. After her self-infection in Tijuana, she didn’t immediately notice any changes in the symptoms of her disease. But her next MRI eight months later displayed shocking results: there was no activity at all. The patches of nerve damage she had seen before were the same, if not smaller.

For the first year, Lawrence’s business was slow. He only treated nine clients. But Lawrence says they responded fantastically. In an online testimony, one man with MS says he hasn’t had an attack since. Lawrence claims he is “essentially cured.”

Spurred by online testimonials about such results, Lawrence's business grew. But in November of 2009, the FDA knocked on Lawrence’s door and told him to stop selling the worms. They informed him that they had classified helminths as an investigational new drug. When the FBI contacted Paypal and froze his accounts, Lawrence and his wife relocated to the U.K. to reconstitute the company there. Dellerba now has his own worm business in the U.K.

Lawrence claims that of the estimated 1,000 clients he has treated, about 90 percent have improved—a claim undocumented by clinical study. Still, the regulatory agency in the U.K. has been positive, he says. He is working to obtain a license to allow doctors to write prescriptions for the worms.

Cautious optimism

Most researchers and doctors say it’s still too early for people to safely infect themselves. As with all novel drugs in the U.S., scientists must rigorously test worms to prove that they are both safe and effective.

“Until the studies are done, you can’t say that it’s an important breakthrough or an important drug that people should run onto the Internet to find,” says Weinstock. But drugs can never be 100 percent safe, says Weinstock. He believes that if helminths are effective, they probably will be safer than current therapies used to treat major diseases.

P’ng Loke, a microbiologist at New York University, agrees. “The safety profile at the moment really looks good for TSO. The problem with businesses like Autoimmune Therapies is that they’re so unregulated. That’s the difference between a prescription drug you get from a doctor and stuff that you order from some random person over the Internet.” Still, Loke would infect his children with TSO if they had a severe autoimmune disorder. Siniscalco says he would do the same.

At this point, Weinstock says the hygiene hypothesis is well along and TSO is safe, but it may be another decade before the therapy is proven effective. And even then, drug companies will need more time to develop an approved drug.

TSO treatment of Crohn’s disease experienced a major setback in October with a failed Coronado Biosciences phase 2 clinical trial with 250 patients. While official results are not yet published, Coronado Biosciences officials say the trial did not meet its goal of improving the symptoms of patients. “If that had worked, it would have become a mainstream idea. Every biotech company would be developing a drug,” sayd Loke. “Now that it failed, we are working backward to find out why.”

Researchers understand why autoimmune disease sufferers want to explore alternative therapies to quell incurable disease symptoms. The side effects from modern drugs can sometimes be as painful and dangerous as the diseases they purport to treat, Weinstock says.

And achieving good health may mean adding back a piece of human biology that has quietly disappeared. Just as probiotic supplements teeming with microbes have wiggled their way into our pillboxes, perhaps one day some of those daily capsules will be filled with worms.

© 2014 Julia Calderone / UC Santa Cruz Science Communication Program

Top

Biographies

Julia Calderone

B.S. (neuroscience) University of California, Santa Cruz

Internship: Scientific American MIND

According to my parents, I was destined to become a detective. My Friday night routine involved a hallway interrogation of my older sister after she waltzed home from a party. I knew most questions had answers, and most answers illuminated a world more interesting than my own. Why not ask?

This tendency served me well in college, where I studied neuroscience. It made sense to inquire relentlessly about our brains. Then, I honed in on the complex genetics of matching organ donors to transplant recipients. I loved making a difference for people, but it felt like my explorations had stopped.

Now I probe scientists on the mating rituals of slugs and the possibility of life on Mars. My childlike curiosity is back—and this time, I don't risk getting smacked by a sibling.

Julia Calderone's website

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Jessie Jordan Jessie Jordan

B.F.A. (illustration) Maryland Institute College of Art

Internships: The Dallas Zoo; Studio Assistant, Amadeo Bachar

My passion for combining art with nature has grown into a career of scientific illustration. My job is to visually communicate scientific topics and concepts clearly and with anatomical accuracy. I enjoy taking on all kinds of projects, collaborating, and learning new things. One of my favorite things to do is to make illustrations out in the field. I hope that my art excites and inspires whoever happens to look at it!

Jessie Jordan's website

Top |