|

| Illustration: Quinn Burrell |

Pains of a different kind in childhood can point to a lifetime of headache. Patricia Waldron asks why we often miss the signs. Illustrated by Quinn Burrell and Lindsay Wright.

Terry Griffith was not prepared for the inconsolable crying of her colicky first child, Abby. One evening, she took her daughter for a drive down a rural road in Cherry Valley, Illinois, hoping the car’s rhythm would lure Abby to sleep. But Terry was so exhausted that a cop pulled her over, suspecting that she was drunk. Her third child, Colin, vomited frequently; just the smell of overcooked broccoli set him off. When he was four, his head suddenly began tilting to one side and he couldn’t walk straight for a few days. A doctor diagnosed him with a rare condition called torticollis.

At the time, the illnesses appeared unconnected. In hindsight, they all may have arisen from a single hereditary disorder in the Griffith family: migraine headaches.

Migraine patients—called migraineurs—are sometimes surprised to learn that their disease is hereditary, says Peter Goadsby, a neurologist at University of California San Francisco Headache Center. “You’ve always had migraine,” he tells them, “since you haven’t altered your genes more or less since conception.” But if that’s true, he asks, “Why does it mostly turn up in adult life? What happens to the first 10 or 15 years?”

We now realize that migraine is not just a bad headache, but a lifelong neurological problem. Migraine means “half of the head,” in reference to its characteristic one-sided headache, but the disorder has many symptoms that evolve with age. Young children who suffer from migraine are often misdiagnosed or don’t receive proper treatment. Goadsby and his colleagues at UCSF are trying to improve awareness of migraine in children—and to find better ways to stop the pain.

Their work builds on a growing suite of studies connecting migraine headaches in adults with colic, abdominal pains, frequent vomiting, and torticollis in children. Funding for research into child migraine is woefully inadequate, neurologists say. But if we learn to recognize this common disease early on, today’s infants could avoid a childhood of undiagnosed pain.

The migraine brain

Headaches first intrigued Goadsby during a medical school lecture on migraine. He was a reluctant student at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia. After class, he told the lecturer that his hypothesis about a circulating, migraine-causing compound was silly. Instead of kicking him out, the teacher asked Goadsby to join his lab and find a better explanation. The lecturer was James Lance, a pioneer of modern headache research, and he became Goadsby’s lifelong mentor and collaborator. Goadsby even named his first child after him.

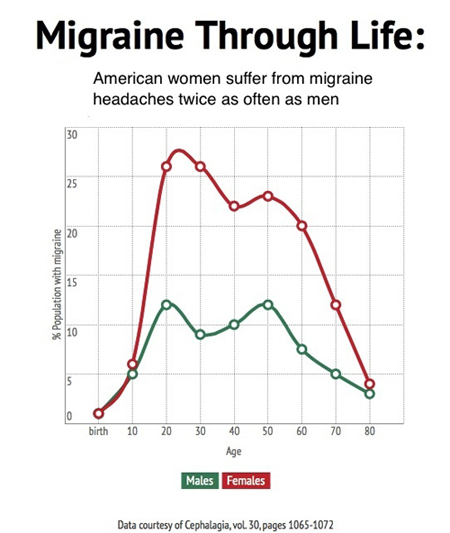

Migraine is so common, yet so overlooked, Goadsby says. It is the third-most-reported disease in the world, according to the World Health Organization, behind cavities and tension headaches. In the United States, migraine afflicts 13 percent of the population and costs $20 billion annually in missed work, doctor’s visits, and lower productivity, according to a 2003 study in the Journal of the American Medical Association. Despite all this, doctors still don’t know how the brain malfunctions to create such chaos.

|

Graphic: Patricia Waldron |

| |

It is hard to adequately describe the misery of migraine headaches. They can cause hammering pain in one side of the head, nausea, confusion, and hypersensitivity. Food can taste strange and may not stay put. Overhead lights may feel unbearably bright, perfume can become a noxious gas, and inside voices can be deafening. Attacks can last hours or days, if untreated.

Doctors can’t test for migraine, so diagnosis rests on headache symptoms and family history. Before the pain hits, some patients see an aura of flashing lights or jagged lines. Others, like Abby Griffith, see holes in their vision. “If I can read text, I know I’m not getting a migraine,” says Abby, now 28. Terry Griffith has painless ocular migraine: distortions she describes as if “Saran Wrap was in front of my eyes.”

For most of the last century, doctors thought dilated blood vessels in the brain caused the throbbing. This “accident of history,” as Goadsby calls it, occurred because the first effective drug, called ergotamine, constricts vessels. Doctors used the compound—which comes from a hallucinatory fungus on rye grains—to staunch bleeding after childbirth, but began prescribing it for migraine headaches in 1938.

Studies from the past five years have quashed the blood vessel idea. MRI images of the brain before and during a migraine show no swelling in the relevant arteries. Another study found that the pounding in the head is out of synch with the heartbeat. “It’s always nice to see some piece of work that completely annihilates a well-held view—very entertaining,” says Goadsby.

Now the prevailing view is that the brain fails to filter out unnecessary information during a migraine, creating sensory overload. But how that happens is still a mystery. Researchers suspect that signals get crossed between the brain and the trigeminal ganglion—a cluster of nerves that branch out to the forehead, eyes, nose and mouth. Also, levels of the neurotransmitter serotonin drop during an attack, which may cause the brain to release certain chemicals that signal pain.

Though sufferers inherit migraine, the genetic causes remain elusive. Studies of hundreds of thousands of genomes from migraineurs and people without migraine have found a handful of related mutations. The genetic glitches do not point to any one tissue or brain function. A subset of these mutations probably alters brain signaling, but researchers are exploring how they affect other tissues as well.

“One of the things we’re looking at is the stomach and intestines,” says Verneri Anttila, a migraine geneticist at Harvard University. Serotonin also affects the gut, he says. “The connection between the brain and the gastrointestinal system is a hot topic in a number of brain diseases at the moment.”

Podcast produced by Patricia Waldron. Click on arrow to play.

When the kids are not all right

Though most people seek treatment for the headaches, head pain is only one symptom of migraine, especially in children. The International Headache Society recognizes several “childhood periodic syndromes,” which often transform into headaches later in life. They include cyclic vomiting syndrome, abdominal migraine, and attacks of vertigo and torticollis. Preventives and rescue drugs—compounds that stop the pain once a migraine starts—can sometimes halt the attacks. The physiological causes are poorly understood, but neurologists believe they result from the same genes that create headaches. If researchers learn what happens in the brain during a migraine, they may be able to explain the cause of periodic syndromes in kids.

In one study of abdominal migraine—unexplained pains in the gut—70 percent of afflicted children later developed migraine headaches, compared to 20 percent of kids without pain. As an adult, Abby Griffith realized that she had had abdominal migraine after eating out. The severe change from a dark restaurant or movie theatre to outdoor sunlight triggers her migraine headaches today, and she believes the phenomenon also caused her abdominal pains. Today, she wears glasses that darken in bright lights.

Abby also experienced rare episodes called Alice in Wonderland syndrome. Just before falling asleep, she hallucinated that her hands were five times too large. “I always thought that was so scary,” she says. In 1955, English psychiatrist John Todd named the syndrome after Alice in Lewis Carroll’s novel. Some speculate that Carroll based Alice’s incident on his own migraine symptoms.

Torticollis, such as Colin Griffith experienced, often appears in children whose families carry the genes for a rare disorder called familial hemiplegic migraine. Goadsby published a paper in 2002 describing four children with torticollis. Two came from a family that carried a known migraine mutation in a protein that imports calcium ions into the cell. After the torticollis disappeared in the young patients, migraine headaches took their place.

The curse of colic

But perhaps the most overlooked periodic syndrome is colic. Doctors define colic as crying for at least three hours a day, for three days each week, for three weeks. Many regard colic as an upset stomach, but Goadsby and his colleague Amy Gelfand suspect it is the earliest periodic syndrome. Gelfand, a pediatric neurologist at the UCSF Headache Center, has a calm voice and a soothing manner—exactly the kind of doctor that a kid with headaches would want to see. Though she has the occasional migraine headache herself, that’s not why she became a neurologist. “When I was a medical student and rotated in neurology, I thought, ‘This is fascinating.’ The brain is really where people are who they are.”

Gelfand says that if colic is a periodic syndrome, then parents should not change the child’s diet. Rather, putting the infant in a quiet dark room, or treating with Tylenol may help. “It could be that they’re not actually in physical pain. They’re simply overwhelmed and expressing that by crying,” she says.

Goadsby and Gelfand analyzed surveys from well-child check-ups for two-month-old babies, just after colicky crying peaks. They found that babies were more than twice as likely to have colic if one of their parents had migraine. A later European study found that kids with migraine headaches were more than 70 percent more likely to have been colicky babies than healthy kids. Goadsby and Gelfand analyzed surveys from well-child check-ups for two-month-old babies, just after colicky crying peaks. They found that babies were more than twice as likely to have colic if one of their parents had migraine. A later European study found that kids with migraine headaches were more than 70 percent more likely to have been colicky babies than healthy kids.

Considering her history of migraine, perhaps it is not surprising that Gelfand’s first baby was fussy. “I didn’t measure if it was really three hours a day,” she says, “but he walked the border, that’s for sure.”

Better treatment for colic could not only preserve a parent’s sanity, but might save a life. Studies have found that inconsolable crying puts babies at risk of being shaken by frustrated caregivers. Hospitalizations for shaken baby syndrome spike soon after colic is at its worst.

When Melissa Torres of Houston, Texas, had her first child five years ago, she was not prepared for Helena’s unending crying. She tried massage, prescription medications, and gave up dairy, but nothing helped. She just carried her baby around the house, hoping the crying would subside. Even when Melissa felt a migraine coming on, she couldn’t put Helena down. “When they hit, it’s like everything has to stop,” she says. “I have to find a way to make sure someone can take care of the kids, or suffer through it, which is always excruciating.” Though Helena’s colic subsided after six months, she still has stomach pains today and is hypersensitive to light, much like Melissa as a child.

Torres believes that if she had known her history of migraine put Helena at risk for colic, then the experience might have been easier to handle. “We were constantly trying to find the environmental factors causing this. Knowing that this is the way she was made would have made me feel better,” she says.

Not faking it

Many pediatricians and most parents—even those with migraine themselves—are unaware of the connection between migraine and periodic syndromes. Perhaps one in ten children have the disorder, clinicians estimate, but diagnosis rates are far lower. In one study, only 7 percent of six-year-olds with headaches had received a diagnosis. Even worse, some adults assume the pain is psychological.

“Migraine was on the psychosomatic medicine list in the 1940s and 1950s. That’s been shot down,” says neurologist Neil Raskin, of the UCSF Medical School. “But there’s still a lot of doctors who seem to think that migraine is basically an emotional problem.”

|

|

| Patricia Waldron narrates this montage of art created by children suffering from migraine headaches. (Click on image to see video.) |

|

Diagnosing periodic syndromes is challenging for pediatricians. Stomach pain and vomiting look like a gastrointestinal disorder, while hallucinations point to epilepsy. The runny nose, watery eyes and ear pressure that accompany many childhood migraine headaches get misdiagnosed as a sinus infection. Studies of colic and periodic syndromes appear in journals that most pediatricians don’t read, says Raskin. “I don’t think pediatricians know much about migraine, period.”

Colin Griffith was 15 before he was diagnosed. He underwent two sinus surgeries, had his vision checked, did extensive allergy testing, and received treatment for an unrelated jaw disorder. When the headaches persisted, he saw two neurologists and tried a list of medications before finally finding a preventive and a rescue drug that worked.

Mismanaged migraine can spiral into chronic headaches, which occur more than 15 days each month. The unrelenting pain forces kids to miss school, birthday parties, summer camps and other childhood experiences. Too much over-the-counter medication can bring on additional headaches. Prescription narcotics can create untreatable headaches, yet some misinformed doctors still prescribe them for kids and adults.

There are no FDA-approved preventive drugs for minors. A nationwide clinical trial is testing whether two migraine preventives are more effective than a placebo in children. However, the study will not finish until 2016.

But there is still hope for treatment. Two rescue drugs are approved for children, and one can be used at age six. Early studies of vitamin B2 and Coenzyme Q10 show potential as preventives. Doctors can also prescribe off-label drugs, or in extreme cases, Botox injections. The drug that relaxes wrinkles can treat chronic headaches when injected into sites on the head and neck.

To prevent triggering an attack, parents should help their kids eat regular meals, establish a sleep schedule and stay hydrated, says Gelfand. Of course, enforcing these routines with teenagers is challenging. Combining behavioral therapy with appropriate drugs is the best approach, multiple studies show.

Despite the advances, research into migraine still falls short, says Goadsby. The American Migraine Foundation is attempting to raise $36 million—just $1 for each migraineur. Goadsby estimates that the National Institutes of Health spend just $0.27 per sufferer. Funding for less common neurological diseases, such as Parkinson’s disease, approaches $100 per patient. “I think it’s outrageous,” says Goadsby. “If I was a migraineur, I’d be hopping mad!”

The Migraine Research Foundation runs a special campaign to fund pediatric research. Juvenile drug development gets stuck in a Catch-22: No one wants to give untested drugs to children, but scaling down the dose of an adult drug doesn’t necessarily work in kids. If the few approved drugs fail, then doctors must use their best judgment to prescribe adult drugs off-label.

“Right now, so much of our therapy is trial and error,” says Gelfand. “I have this list of medications I can choose from. How do I make this choice?”

New discoveries will come too late to help most migraine sufferers. But with better recommendations, Gelfand says she can help children to overcome their headaches sooner and stop missing out on the joys of childhood.

__________

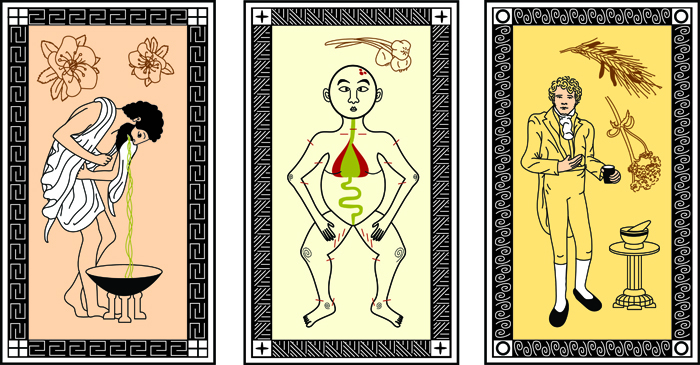

Sidebar: A Painful History

|

| Illustration: Lindsay Wright |

Mesopotamian poems mentioned migraine as early as 3000 B.C.E. But the first known treatment didn’t arise until 400 B.C.E., when Hippocrates recommended vomiting to relieve pain, and consuming a toxic plant called hellebore, which flushes out bodily substances. Arabic physicians in the 11th to 13th centuries tried trephining—drilling a hole in the poor migraineur’s head—and cuts to the scalp for inserting garlic cloves. They also recommended heated irons and the general cure-all: bloodletting.

In the 1750s, one doctor recommended large doses of the sedative herb valerian. J.R. Graham and H.G. Wolff published a study on the first effective migraine drug, ergotamine, in 1938. The compound comes from a fungus that grows on rye, which causes hallucinations and is the source of LSD.

Migraine drugs advanced little until the 1990s, when rescue drugs called triptans entered the market. Today, pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly is developing a new wave of drugs made from antibodies that block a signaling peptide in the brain. Called CGRP, the peptide likely plays a role in pain transmission. The company paid $57.1 million for exclusive rights. Researchers are still testing the compound, but if all goes well, it may be available within four years.

© 2014 Patricia Waldron / UC Santa Cruz Science Communication Program

Top

Biographies

Patricia Waldron Patricia Waldron

B.A. (biology) Grinnell College

M.S. (microbiology) University of Massachusetts, Amherst

Internship: Inside Science News Service

I met my first science writer, Brian, while watching “The Thing” on a snowbound day in Antarctica. I spent that icy summer as a lab tech, puréeing fish for their DNA. Meanwhile, Brian helicoptered to field camps, photographed penguins and wrote stories for scientists and snow-shovelers alike. Clearly, he had the better job, but I was too focused on developing my molecular biology skills to notice.

I used those skills for several years to track the lives of underground microbes. I loved learning about the bacteria, but the tedium of lab work left me feeling one-dimensional. I recalled that Antarctic day and started writing about science for snow-shovelers. I kept going because my first stories about tuberculosis and STD rates in Oklahoma felt more valuable—both personally and societally—than all of my experiments combined.

Patricia Waldron's website

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Quinn Burrell Quinn Burrell

B.S. (evolutionary anthropology) University of Michigan

Internships: ECOS Communications (Boulder, CO); Rocky Mountain Bird Observatory (Brighton, CO)

I spent my childhood wandering the halls of the natural history museum where my mother worked and accompanying her on bat research trips. This has given me a dual appreciation for ethanol-scented research labs and the biological information available in nature. As an illustrator, I strive to merge the complexity of academic research with the simple beauty of organisms in their habitat.

My other interests include human anatomy/physiology, marching band, running, and playing fetch with my cat, Noctivagans. I would like to give special thanks to my cousin and model for this project, Saysha Dewey.

Quinn Burrell's website

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Lindsay Wright Lindsay Wright

B.A. (studio arts) University of Pittsburgh

Internships: Carnegie Museum of Natural History; ZooBooks (Dinosaur Zootles)

Our natural world is full of amazing things. There are so many places to explore, innovative designs to discover, and advantageous adaptations to understand. Earth’s diverse ecosystems offer a plethora of illustration subjects to be drawn in excruciating detail. I am a scientific illustrator because I believe understanding the natural world, even a little, is important for everyone. Through my enthusiasm for biology and background in art, I make identifying patterns in the tree of life contagious. Scientists are working every day to understand the parts, relate the pieces and build the puzzle of our knowledge of this magnificent planet. Their work is the fuel my illustrations use to spark interest and form a permanent connection between the minds of man and the natural world.

Lindsay Wright's website

Top |